The Drums' Jonny Pierce on the Past, Facing Childhood Trauma, and the Essence of Vulnerability

This is a free post from Larry Fitzmaurice's Last Donut of the Night newsletter. Paying subscribers also get two Baker's Dozen playlists a week, which include a collection of music I've been listening to along with some critical thoughts around the music itself. And, hey, I'm running a sale on annual subscriptions right now! 25% off, you can grab that here.

I'd say the Drums are underrated at this point and, critically, they are, but also, just go to one of their shows, their fanbase is extremely passionate at this point...I've been a longtime fan of Jonny Pierce's songwriting since the beginning and the latest album, Jonny, might be the band's best to date, heading back to the indie-pop sound that especially marked their first two albums. It's also his most vulnerable record to date, expanding on his history of surviving childhood abuse that we spoke about a little the last time I interviewed him for Stereogum. We hopped on a call earlier this month to talk about what went into putting this new album together, and the power he finds in his own self-expression.

You've lived back and forth between coasts the last few years. What's that been like?

Los Angeles is a really special place for me, mainly because there's a fanbase for the Drums in southern California. They're the most passionate, loving, and there-for-me-always type of fans. As far as being in the Drums, L.A. is the place for me. As far as my personhood, a place where I can feel good at most of the time, it's New York. It's a funny thing in my life. When I was young, I thought, "I'm gonna see the world" — which I did — "and maybe I'll live in Europe." You have these ideas of where your life will end up, and I keep finding myself moving back to the Northeast. There's something in me that's settling into that as an idea and a feeling of home. I've put away this idea that I'll live here, there, and everywhere and just try everything.

I have a greater self-understanding of what I actually need these days, and what brings me joy—what makes me happy. And it's the opposite of bouncing around, trying to live in Europe, being on tour. What brings me the most meaning, fulfillment, and satisfaction in my life is being really still and calm. Being in New York—away from where I grew up, but somehow on some level still attached to where I grew up—is this funny little sweet spot for me.

You mentioned being on tour a lot. When I saw you play Warsaw in 2019, I was really surprised at how passionate the band's fanbase is when it comes to the entire catalogue—which is kind of rare when it comes to your peers from when you started coming up.

My fans are deeply passionate across the board. It's been a real journey to find myself in a place where I can experience that passion with the people who show up to my concerts. In the past, if you asked me about this, I'd say, "Oh, it's great, it's the best." But I wasn't really so attached to the experience of being onstage and being in my body. It's a new thing for me—it feels exotic to be able to be onstage, take this all in, and let it hit my heart.

There's a lot of theories out there on why people still listen to the Drums [Laughs]. We're getting more streams than we've ever had, and the shows are getting even more exciting too—but, from my vantage point, there's always been excitement about the Drums. Part of our staying power is that I'm a weirdo. I grew up in a very unconventional space and had to figure everything out for myself, without any guidance or a support system. When you've had that experience growing up, you come out of the oven a little different.

For me, there was a lot of pain in my childhood and teenage years, and I still experience pain now. From the beginning of the Drums, I wanted to talk about my pain, and not in generic terms. Maybe I'm getting analytical, but I wanted to be deeply seen and understood, and my subconcious made that choice for me. "If you tell everyone what's going on, they will know you and they will love you." It's this quest for belonging that's where my vulnerability started—and it's interesting, because a lot of people would go in the other direction. They'd harden and not share anything. But something in me just wanted to be known.

I don't think that there's another band in the world that is making music quite like the Drums are, and I don't think there's another frontman being as honest and vulnerable as I am. I know that sounds like a big thing to say, but I think there's a real need for that to be more out in the world. I got asked the other day, "Aren't you scared of sharing so much out into the world? Doesn't that make you feel nervous?" For me, it's the opposite. Not sharing feels more scary—it feels meaningless to me at this point. I'm not sure I'd even want to make music if I couldn't express the deepest parts of my heart. That is a reason why the Drums have maintained and continued to build a fanbase. As I share my heart more, people get more excited about what I'm doing.

I've always been on a little raft in the river. I never jumped on a boat with a bunch of other bands. When we started coming up, people were saying, "Oh, it's the Brooklyn sound." There was this idea that the Drums were running around with Chairlift, Grizzly Bear, and Vampire Weekend—that we were all hanging out all the time. I think they were hanging out, but I was never hanging out with anyone. I was a loner through and through. There's also a part of me that has an aversion to joining the crowd. Some of that has to do with how I grew up—my dad being a pastor and there being a congregation that blindly followed. I'm very aware of when I'm getting sucked into a scene, so I try to pull away and maintain my own little space. That's helped me find my own niche, but it also is just what's happening. It feels genuine, it feels me.

When you boil it all down, I have a willingness to go some places that other bands who are viewed as my contemporaries don't want to go—and I'm really OK with saying that.

I think this new record's pretty fantastic.

It's the only album of mine that I've ever been able to play to myself and love front-to-back. In the past, I was in such a place of self-hate that anything I did, I'd hate. I made Portamento, I put it in the world, and then I never listened to it again. I turn my back on my work. Everything goes back to childhood, so you're gonna hear me talk about it a lot, but if something is behind you, it's painful. I put work out in the world for 10 years and was really ashamed and scared of it. I'd never face it or listen to it.

I think this record is evidence of a lot of work I've done in therapy, and with psilocybin—and also, gaining more understanding about myself as I get older, what works for me and what doesn't. It's a whole new experience, to be able to love the work that I do. There's a big difference between this album and everything I've ever done, which is that I'm different. I was the same character for the last four or five albums, and there's been a sort of rebirth now. I'm still singing about longing for belonging, being misunderstood—those themes are still there. But in the past, when I sang about those things, it was from a place of chaos—I was stabbing in the dark emotionally, reaching out and crying from a place of deep pain and confusion. With this album, it almost felt like I was writing it from a place of knowledge, wisdom, and understanding of myself.

I was able to lovingly make these songs. I gave each song its own space. I sometimes took months off without recording a single note or lyric. It was the first time I'd been gentle with myself during the recording process. In the past, I'd drink six iced coffees in a row and demand that I write two songs every day until I had an album ready—which, looking back, seems really harsh on myself, like a punishment. There was a lot of love, learning and understanding what I need while making this album, so when I listen to it, I enter a soft, gentle, loving space.

You mentioned not being able to revisit your past work anymore. The funny thing is, I thought of Portamento almost immediately with this record—calling back to that Sarah Records and Labrador sound that I first heard in your music.

You don't hear anyone talk about those labels anymore.

Yeah, younger people don't really get into that stuff anymore the way I did when I was younger. It's a bit shocking.

When the band started, we were talking a lot about Sarah Records. We envisioned ourselves as being signed to that label and being that kind of band. We were deeply in love with that music. Sincerely Yours, too—all that weird bedroom pop was so charming to us, it was a huge influence.

At this point, are you still not able to revisit your earlier work?

It's like looking at an old photo album, right? There's a lot of feelings that can come up, and some of them are sweet, and some of them are maybe a little bit sad. Maybe a little angry, even. I think I'm in this process of flipping through the photo album of my portfolio and learning to be sweeter about what those albums sounded like—to embrace the Jonny that was younger and doing his best with what he knew about himself, and to let things just be that.

I guess it's an issue of self-acceptance. The more I learn to love myself and younger versions of myself, the more I appreciate how my older records sound. It's a very weird thing for a decade, to have people in my face every day say, "I fucking love your band, this album changed my life, we played this song at my wedding," and me thinking, "I don't get it, I don't know why you'd use this in your wedding, bad decision." I was so disconnected from the work I was putting out because I was so disconnected from myself. I can see the pain I was in, but I want to go back and give that version of me a hug.

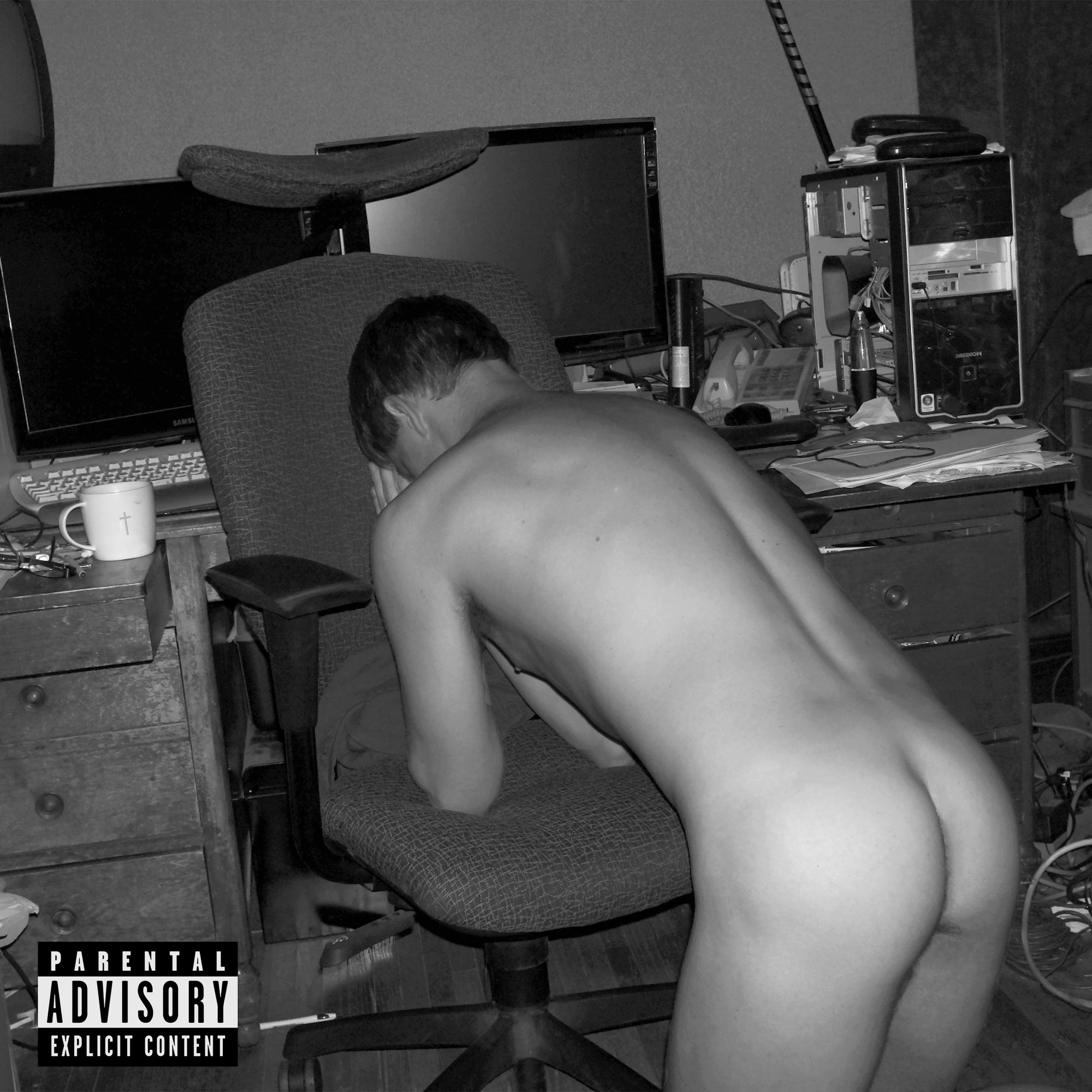

I wanted to talk about the photos you took of yourself that are included with this album, which are really striking. We talked about your family history the last time we spoke, and here you're literally exposing new sides of yourself.

I go back and forth all the time about how I feel about these photos. One day, I think, "Fuck yeah, I'm such a badass, look at how punk, daring, and courageous I am," and then I'll be in a different mood the next day and I can't even look at them. I bounce back and forth from these two feelings about them. I think it's because a few things that were happening when I took the photos, which represent something beautiful for me even as it feels darker and more difficult.

A friend gave me a camera, and I knew I wanted to take some photos of myself—I just didn't know what I wanted to do. I ended up driving up to my childhood home upstate and climbed into my childhood bedroom window while my parents were out of the house—I waited until Sunday morning, because I knew they'd be at service. I made sure no one was there, and I just took my clothes off without thinking about it. It was just something that I felt that I needed to do. I set up my tripod and ended up taking self-portraits with a self-timer of myself, nude, in many places in my childhood home where I experienced real pain and suffering.

The beautiful way to look at it, for me, is that I like to think that I'm taking back power in these spaces where I felt powerless—it was like a reclaiming. It was maybe a righteous holy rebellion, a fuck-you. "This is my space now, this is a re-do for me." I like that idea, and I wish that's all it was, but there's also still a question mark about whether there's a Stockholm Syndrome element to it. Of all the places in the world to be naked, to go back to the place of your abuse and make yourself incredibly vulnerable by being unclothed. I just wonder why I had that draw to go to a place of suffering and pain. Why didn't I do a photoshoot in the forest with no clothes on? I don't know if I'll ever know.

It reflects, for me, how the new album has songs that go together thematically, while there's other songs at odds with the ones just before them. "Harms" is about me being angry and crying out about my suffering as a child, and then it snaps into the next song, which is a song of comfort, tenderness, and sweetness. I guess they relate in some way—one demands the other—but I thought about what these photos represent for me, and it's a reflection of the diversity of emotion and feeling on the album. Also, this album is love letter after love letter to the younger versions of myself—letting them speak. How beautiful the younger version of me ten years ago took these photos and is giving them to present-day me! It feels like there's a lot of love and healing. I had to use those photos—I'd been holding on to them for a long time, and I thought I'd never use them, but this album was asking for it.

"Teach My Body" stood out to me specifically in context with the album. Talk to me about being in touch with your body.

These two ideas play off each other. Which do you tackle first? Do you teach your soul and your body follows suit, or do you teach your body that it's safe and OK, and then your soul is awakened or comforted? I think they go hand-in-hand. It's a bit of a tango. You're feeding into both little by little, and sometimes your body needs something more than your emotional world.

When I was making this album, I was paying a lot of attention to the idea of touch. There are parts of me that have been afraid of touch in my life, and there were times I'd been touched in a harmful way. I had this longing to be touched physically and caressed, in a sweet and parental way, but also in an erotic, sexual, and sensual way. This song in particular is about harms done to me when I was much younger, and how I'm trying to find connection in sexual fulfillment. I'm trying to figure out how to talk about this song—it's a delicate one, no one's asked about it yet. [Laughs]

When I was making this record, I was in my cabin in upstate New York for a year, mostly on my own. I had a few visitors here and there, but I was mostly in isolation. I started this practice where I caressed myself every morning in bed for 15 or 20 minutes. It was in a sweet way, not a sensual way. Just saying to myself as I was doing it, "I'm so proud of you Jonny, I love you so much." I didn't even know what I was doing—it was like the photos I took, I was like, "This is what we should do now." I'd like to think it was me being in tune with my body. I was teaching my body that touch can be sweet, beneficial, and healthy, and it can make you feel safe. That was part of that journey for me. I was doing a lot of work in that space, so that song really wanted to be written.

It was the hardest song for me to finish. I just couldn't figure it out! A lot of the time, my songs just click together. With this one, I was taking it apart a hundred times. There was a time I scrapped everything, deleted the session, and rebuilt it all over again. Our subconscious does crazy things, and there may have been a deep reluctance to put a song like this out in the world and be so vulnerable. There may have been things in play that I don't even understand—a self-sabotage in the process of making this. Maybe the snare sounded just fine, but I heard it as not sounding good. I have to wonder if that's why that process was so difficult. If it was a song about surfing, maybe it'd have been more easy to write. [Laughs]

As you continue on this path of extreme vulnerability, does it get easier or harder? Or is it just situational?

I think I'm at a point in my career, and in my life, where I just want things to matter. I want the things I do to have meaning. I do this full-body check when I'm getting ready to write something quite vulnerable where I sink into my body and sniff around a bit, listening for a voice that might say, "This doesn't feel like a healthy type of vulnerability." I try to honor those voices. Anything that I do put out in the world that feels vulnerable and raw, I have really done the spiritual homework of making sure it lines up with what feels good and healthy for me to talk about. It's not this reckless, "I'm gonna tell everyone every time I cry" thing. It's very considered.

I think about things a lot. My brain just goes and goes and goes. I think I'm just going to continue on this path. The other day, I was talking to a friend and I said, "Maybe my next record can be a party record to be sweet relief from all this heaviness." And by the time I was done with that sentence, I thought, "Fuck that. No way." [Laughs] It would do nothing for me, and it would mean nothing to me. Even if it did, it's not where my heart is taking me. As long as I'm on this concentrated path of self-discovery, whether it's short or long, that's what I'm gonna be writing about.

I can't really find the enthusiasm to write a song if I don't feel like it's really coming from my heart. I used to say, "Gosh, I'm such a dramatic artist. God, Jonny with the drama." I started thinking about it, and I realized that I have a new way to look at it. I'm not dramatic, it's just that much of the world is very closed off from their emotions, and from sharing with each other. People are pretty guarded. When we're little kids, we express what we need, and then we become a teenager and our emotions are raw. When we become adults, there's this pressure to belong, and part of that for a lot of people is having to come across as having it all figured out. So they put on the armor and have a more tidy existence, at least in terms of the optics.

But they pay a big price—not only disconnection from others, because you're not letting other people in, but from yourself. In a way, I'm trying to lead by example, and what I'm doing is what I'd love to see more artists and people do—to express how they're feeling, and to be known. That's all we want, it's the groundwork to be loved. If people don't know you, how could they love who you are?