Bombay Bicycle Club's Jamie MacColl on Relationships, Collaboration, the UK Music Press, and Tackling Cybercrime

This is a free post from Larry Fitzmaurice's Last Donut of the Night newsletter. Paid subscribers get two Baker's Dozen playlists every week, which come with music criticism and musings around music I've been listening to. And, hey, I'm running a week-long Halloween sale! 25% off annual subscriptions, that's $22.50/year instead of the usual $30. Grab the sale here.

OK, let's get down to business! I'm a fan of UK indie veterans Bombay Bicycle Club and I think their latest album My Big Day is one of their most fascinatingly eclectic to date, with a roster of collaborators that only adds positively to their very hard to pin down sound. I hopped on a call with guitarist and longtime Twitter mutual Jamie MacColl to talk about the latest LP and a host of other topics, and we kicked things off with some chatter about being the parent to a toddler at the moment...

How has parenting been?

I felt very anxious about it before, and was quite hung up on the idea that I'd be a bad father. But a lot of that went away after he was born. I've enjoyed all of it, basically—even the sleepless nights have your moments where you feel like only you can put someone back to sleep. Jack had a baby two months before me as well, so that's been a shared experience.

What's it like to balance it with your career?

My relationship to music and being a father is shaped by my own experiences having a professional musician as a father. When I was growing up, my dad was touring a lot in North America for the first five or six years of my life—he was David Gray's session guitarist. They'd go on these three-to-four month-long tours. I probably just didn't see him very much growing up. I remember he came back once and my brother, who was six months old, didn't know who he was. I've always had that in the back of my mind about being a father myself. It's definitely shaped the fact that we're not going to tour as much as when we were 24. We've basically accepted that it has financial and success costs, just because we won't be able to work the band as hard. But I'd rather have a good relationship with my son. [Laughs] Not that I had a bad relationship with my father, but it has consequences.

I feel like a lot of non-American guitar bands have a White Ladder influence these days. David Gray was doing something very post-genre-y early on before that really became a thing. Would you say that era of music was an influence on Bombay Bicycle Club?

I wouldn't say his music specifically was, although we did record our acoustic album Flaws at the studio he owned at the time, which is now owned by Paul Epworth. My dad produced half of the songs on that record. But I completely agree that it's a post-genre album—electronica meets singer-songwriter, you get the Postal Service from that too. He slogged away for ten years before that record really happened, and my dad worked with him for 20 years, but that was the one record he wasn't involved in. [Laughs]

I feel like a lot of rock and pop-rock bands have made a name off of being hard to pin down these days, but you guys were ahead of that by a few years with So Long, See You Tomorrow. I'm curious to hear what you guys perceive to be your own evolution of sound, including what you try to avoid.

I was thinking about whether there's Bombay Bicycle Club tropes, and whether we consciously try to avoid them in the studio. For the first four records—which we did in five years, between the age of 18 and 23—at that age, you're just discovering new things all the time. You don't really know who you are, and we certainly didn't have a fixed idea about the music we wanted to make or a grand plan for the band. A lot of the evolution of our sound is Jack discovering new kinds of music and essentially learning how to be a producer on the go. A Different Kind of Fix and So Long, See You Tomorrow came out of the curiosity of learning how to be a producer that bases their music off of sampling older records, world music and what have you.

A lot of the albums have been a reaction to our previous work. After we made a jangly indie-rock record—which was pigeonholed a bit and had a bit more subtlety than people ascribed to it at the time, but hey ho—our reaction to that was to go away and make a folky acoustic record. Within that period we started discovering a lot of '60s folk singers, and that music resonated with us. Plus, it was easy to make. We'd been in an expensive studio for months making the first record, so our reaction was to go to Jack's bedroom in his parents' house, which was easy and fun by comparison. With So Long, See You Tomorrow, we went down a real maximalist route as a reaction to Flaws being so minimal.

As an American who grew up reading the British music press, they've always had the tendency to pigeonhole and overhype. It's a very specific and, from my perspective, entertaining mechanism compared to what we have and don't have in the States. You guys have been through it with the British music press in general. What has navigating that and the music industry in the UK been like?

Here's a question in return: Do you think that characterization of the British music press still exists?

I don't know! There was a band on the cover of NME last month that everyone was very surprised about, I can't remember their name.

I can't remember them either, but yeah, there was another big conversation around industry plants. That's what happens when there's women as frontpeople.

Yeah, the whole industry plant conversation usually reeks of misogyny to me. But it was interesting to have people talk about the cover of NME again, that doesn't really happen anymore.

There's still a few small monthlies in the UK, like This Is Fake DIY. But when we came through in 2005, guitar music felt like such an essential part of British music culture. It charted. Franz Ferdinand or Bloc Party had #1 or top-10 singles, which does not happen anymore for guitar music in the UK. I'm sure the 1975 haven't had any charting singles.

But I often felt very burned by that style of tabloid reporting from NME. I'm sure this is just naïveté from being 18 or 19, but I often felt like we were being misquoted, or that they were sensationalizing what we said. We also probably weren't thinking much about what we said, because we didn't have media training, because we always refused media training. But so much of it was oriented around in reaction to what happened in the '90s with Britpop. They were always trying to manufacture rivalries or nudge you towards making negative comments about other bands, which feels like a zero-sum way to think about music—although I get that it can be effective.

When we did the NME Tour with the Maccabees, the Big Pink, and the Drums, there was a story in the magazine that the Big Pink were putting ketamine in our dressing room every night. They thought it was funny because we were 19 and they were corrupting us. It was a half-page in the magazine, and my mum saw it and was furious. After that, I was quite reticent.

You asked me before if the British music press as we once knew it really exists anymore, and it's pretty clear that it doesn't. American music press doesn't exist much anymore, either. Do you think we're losing something by not having a stronger music press?

My mum's a journalist—she was the editor of a glossy magazine for a while—so my gut feeling is for me to say that it's a bad thing that we don't have more print media, or a larger and more well-funded music press. But then again, as I said, I had quite a lot of negative experiences with music journalists in the UK when I was younger, which I'd be fine with navigating now. But I think it's a bad thing, because having more print and online media that's well-funded creates opportunities for journalists to tell interesting stories and do robust, thoughtful criticism, which is an essential part of culture.

This new record is the second one following the band's hiatus. How does it feel being fully back in the swing of things a few years out from getting back into it full-time?

I've been thinking about this recently while thinking about the making of the last album. The hiatus was three or four years, and we were pretty burned out at the end of 2014 after touring So Long, See You Tomorrow. The relationships in the band had taken a battering, and when we got back together to make Everything Else Has Gone Wrong, we were in damage limitation mode, to some extent. When I listen back to that record, a lot of it feels quite safe to me. The latter half of the album feels like watered down versions of what would've gone on our earlier records—lesser versions, to be blunt. We were also in L.A. making that, and we were very relaxed and having a good time, and we probably weren't holding each other to account how we normally would. There was a lot of focus on not ruffling each others' feathers too much and just getting along.

I think there's really strong songs on that record, but I also think it's our weakest, to be honest. With this one, we've reached the point again where we're less focused on protecting one another—although that is still a consideration—and more on pushing the boat out as far as we can, and challenging ourselves and each other. There's songs on this record that we 100% would've been too scared to put on the last one. The other thing is, coming out of the hiatus, there was still a sense of being a distinction between Jack's solo music and Bombay Bicycle Club. The band's at their best when that distinction doesn't exist, and we embrace trying as many different things as possible—when things are feeling new and exciting.

You guys are coming up on 20 years as a band—that's a long time to know anybody, in any capacity. Relationships are tough! Tell me about what the work is like when it comes to maintaining relationships in the band.

I'm not even sure I'd characterize our relationship as friendship anymore. It's like family, or at the least it's more heightened than any other friendship I have, because it tangles up so many different aspects of each others' lives, and there's obviously also a business relationship that's complicated as well.

My relationship with my wife is one of the few I have where I consciously think about putting work into maintaining it. With the band, I'm probably more conscious about how my actions are making them feel, which has come through a lot of hard lessons and arguments. We all have a lot of different personalities. I'm not sure I'm extroverted, but I'm the least introverted in the band. We're not a group that regularly shares how we're feeling, but I've reached the point where I think I know what I'm feeling most of the time [Laughs], and I can react to that. As a musician, especially one that started at 18, there's a lot of key social skills you don't develop. When we went on hiatus, there were a few things we had to learn how to do socially, which has made the last few years a lot easier as well.

How old are you?

33.

I'm 35, but turning 36 on Friday. [Editor's note: This interview was conducted in July of 2023. I'm 36 now.]

How are you feeling about that?

I feel pretty good about it. I'm like, "Is 36 kind of old?" And then I'm like, "No, it's fine."

I just feel so fucking old in terms of the world of popular and alternative music.

Music, and the music industry, and music writing, can be a young person's game, to a fault.

With a band like us, it's not even the age we're judged by, it's "How long has the band been going for?" 33 is actually quite young in the industry, but we're treated as a different generation because how long this band has gone for. It's difficult to reconcile when others at this age are quite early on in their career. I'm happier now than I was back then, but I'm treated like an old man by 19-year-olds on TikTok.

You gotta stay off TikTok, man.

But we have to be there!

You guys worked with a lot of different people on this record. What was it like to bring others into your creative world?

We've been doing it for a long time in some ways, because since Flaws we've had guest singers on the record—but it tended to be one person. There weren't features, it was just part of the character of the album. It's very different now. In some cases, these are people we've never even met before. There's negotiating release schedules, and which songs can be singles. Several publicists need to have calls over it. It's not quite as relaxing. But I've really enjoyed working with other people on this record. In some cases, the working has been distant and minimal. Jay Som was the collaboration I enjoyed the most, because she was actually doing songwriting on it. She wrote lyrics and came up with new melodies. I liked her music a lot before, but I admire her even more after this process. She's a great producer, apart from everything else. I'd really love to work with her again in the future.

With Damon Albarn, his voice is so distinctive, and he did write the verses that he's singing on with Jack as well. I'm such a big Blur fan—they were one of my favorite bands growing up. If you told me when I was 15 or 16 that we'd have Damon singing on one of our records, I'd have lost my mind. I was also very excited about Nilufer Yanya, because I thought her record last year was one of the best of the year. She's a very interesting songwriter and singer, and is not someone on paper who you'd imagine on our records—but we actually wrote that song with her in mind, before we'd even asked her. We were digging the idea of her being on a groovy, heavy rock song, and it worked really well. It might be my favorite feature on the record.

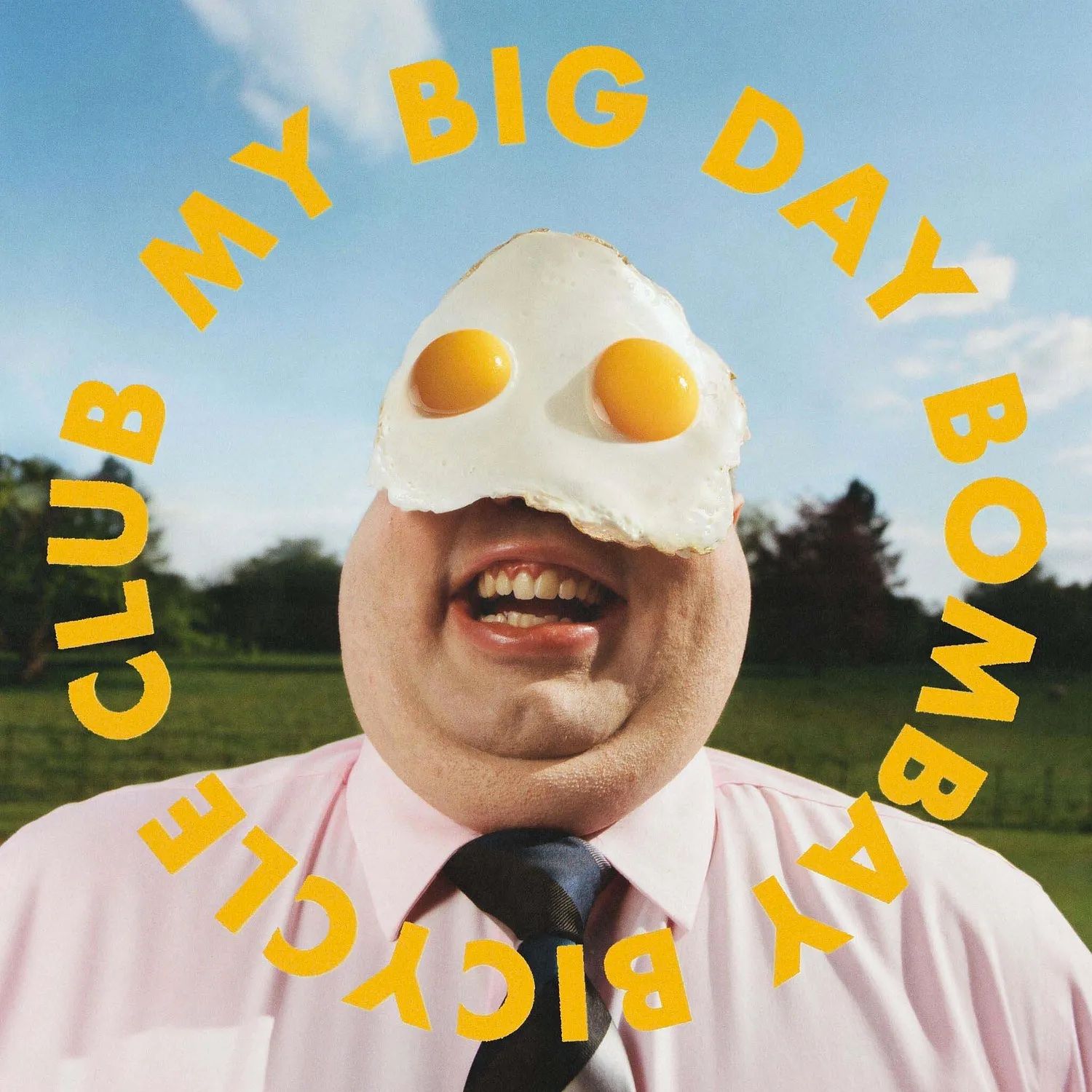

I wanted to ask you about the album cover.

[Laughs] I've never seen so many people pissed off by an album cover, to be honest. Sometimes I go on r/Indieheads when I feel like punishing myself, and there was a discussion about it where people were so angry, which I don't really understand. I would never not buy an album from a band I like because of a cover. There's an element of over-the-top absurdity to the album—it's a bit silly at times, in a good way. We wanted to embrace that with the cover. Our album covers have often been gentle, soft, safe illustrations, and this was a reaction against that. It was about embracing the absurd and I guess, to some people, grotesque—although, as an overweight bald man, I don't find it grotesque.

Tell me about what you do with RUSI. Walk me through what that part of your life is like.

When the band went on hiatus in 2015, I went to university for the first time and decided to study war, as you do when you're the grandson of pacifist Socialists. [Laughs] I'd always been interested in history as a teenager. I also felt like burned after the band went on hiatus and wanted to have a proper break from music for a while after nonstop touring. I ended up working for a private cyberthreat intelligence company in my spare time. I won't get into loads of details about what it involves, but it's basically tracking what Russia, China, North Korea, or Iran are doing against the UK.

After a few years of that, I ended up at RISI, which is a pretty traditional think tank that's since took on some nontraditional issues, like financial crime and money laundering. It's mostly about producing very long reports that I'm not sure anyone reads. [Laughs] I've probably interviewed 300 or 400 people in the last few years, so I've become very familiar with your process. I perhaps have more empathy for music journalists now than when I was 20. I've done projects a lot where it's for the UK government, some of which is academic research.

The stuff I've been working on in the last few years involves ransomware—there's been a lot of prominent attacks against the US and UK in the last few years. My work is figuring out what to do about that, and I've also spent a lot of my time interviewing victims of cybercrime, which is quite difficult work. But I'd like to think it's important. It's very hard to connect any of it to music in any way, which I'm struggling with as the band gets busier. It's not the kind of thing where they're relevant to each other. I do quite a lot of work on emerging technology, and I've become quite interested in AI and music and what that future looks like, and what the place is for musicians like me in that future. I don't know what the answer is [Laughs], but I don't think it's great.