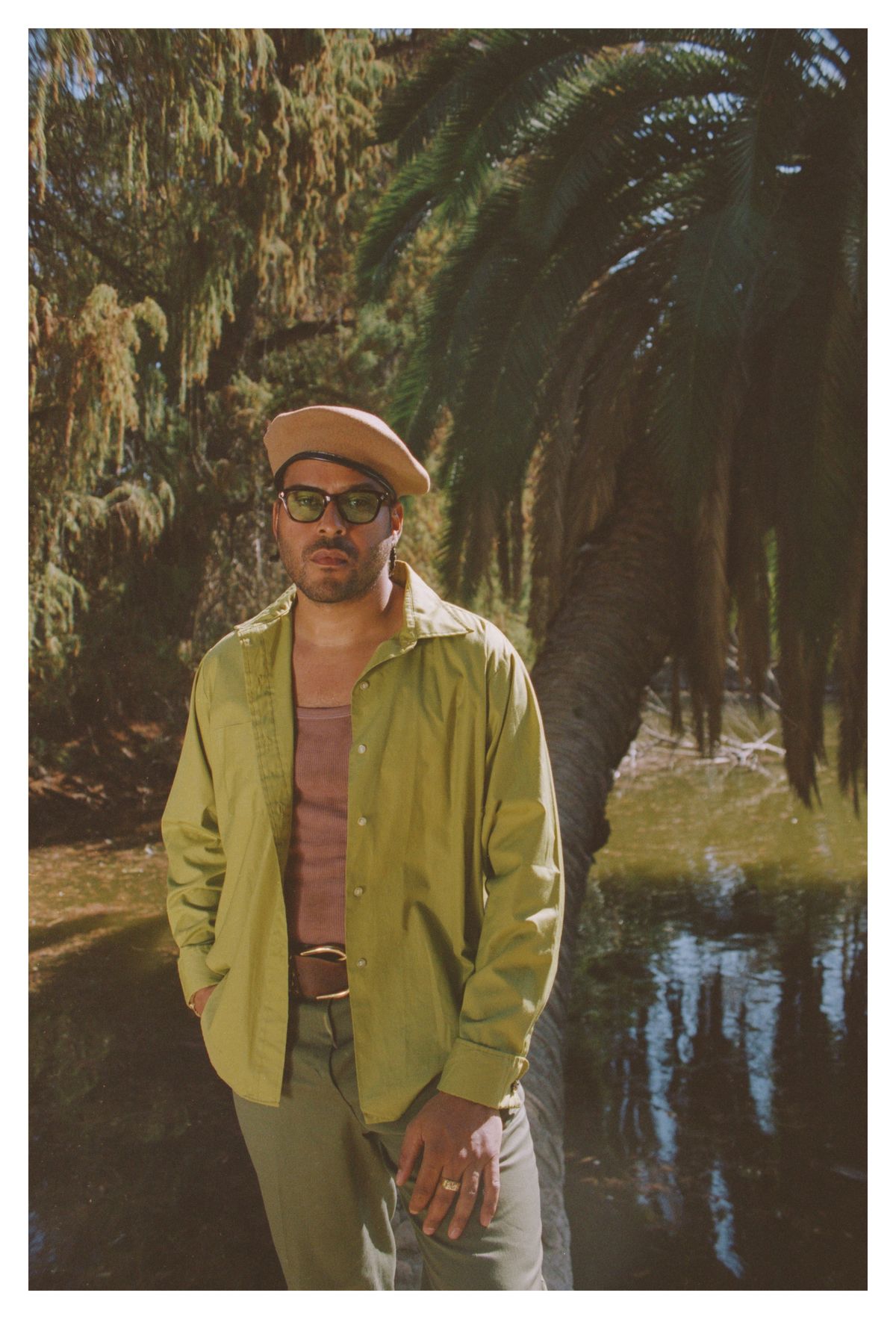

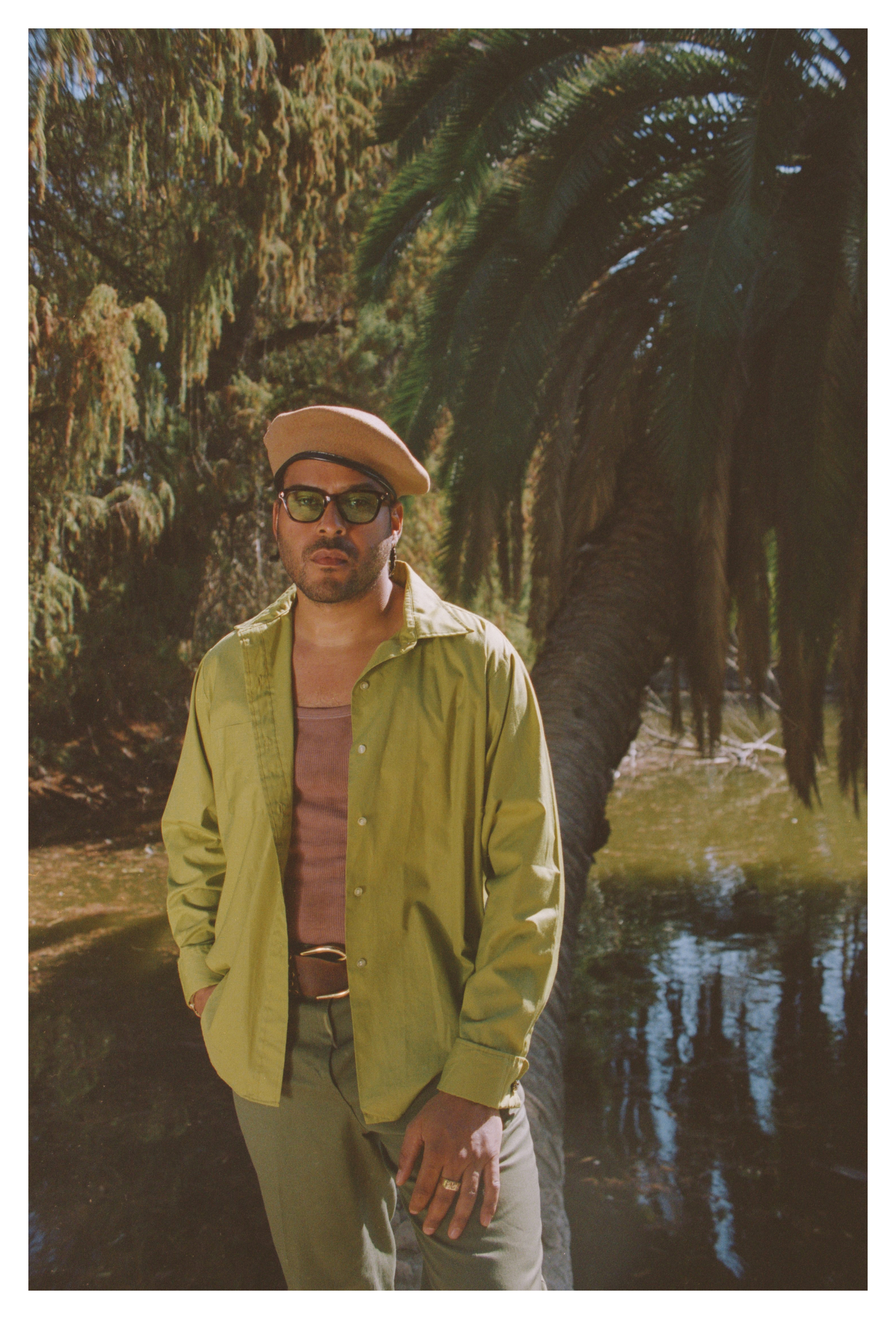

Twin Shadow's George Lewis Jr. on Mental Health, Going Indie Again, and Reflecting on the Past

For a time, I'd see George Lewis Jr. everywhere. In the years between two interviews I did with him—one controversial chat for Pitchfork in 2012, and another more contemplative convo for the FADER in 2014—the 38-year-old singer and songwriter behind Twin Shadow would pop up where I least expected him. One time I felt a tap on my shoulder in line at the grocery store, and there he was; in the wee hours of the morning while taking a break from a Frankie Knuckles set with a friend at Cameo Gallery (a double-RIP if there ever was one), I saw him sauntering down North 7th.

Most recently, I saw George on my timeline, announcing his new album—a self-titled effort out July 9—would be independently released. The last few Twin Shadow albums came out on Warner Bros., so I was naturally curious about the shift in release strategies as well as what he's been up to since we last spoke. I slid into his DMs, and a few emails later we had the chat you'll read below.

How have you been?

I'm in my place in Beechwood Canyon right now. I've been good, just like everyone else—doing the pandemic shuffle. It was very good to me, except that I got vaccinated months ago and I still caught COVID after. I made it through the war, and then foxhole-style got nabbed.

What was getting COVID after being vaccinated like?

I guess it's rare, or nobody's talking about it. It wasn't too bad except completely losing my sense of smell, which still hasn't totally come back. That's one of the more eerie things about it, I think. I don't think people really realize what a necessity smell is, or how it can fog your mind and put you into a depression. It's such a base instinct that when it's gone you lose your footing. So that was weird. But honestly, I can't complain. It was really mild.

What's your last year been like in general?

I was lucky, because in 2019 I'd gone down to the Dominican Republic for a few months and was already concentrating on making a new record. So I already had that momentum when COVID was starting. Everyone's like, "Oh, you made your COVID record," but conceptually, it was already done. But what the quarantine offered me—which it didn't offer a lot of people I know—was this quietness to sit with the material I made.

I've never been an iterative person. Whatever happens in the studio, I put it out. This gave me a chance to become my own editor for the first time, which gave me a sort of peace. It literally gave me quiet. You walked outside and it was just more quiet because there wasn't 20 things to go to—events, dinners, whatever. It created this peaceful environment for me to iterate, make careful decisions, and push things further, and I was very happy to do that. I know it was hell for a lot of other people, but with caution I would say it was a very productive time for me.

You're releasing this new album on your own after a period of time on a major label.

I could talk about these major shifts from indie to major and back to indie in a romantic way, and I wish it was dramatic enough to tell some exciting tale. But the truth is that I was never truly "indie." You could say I had indie sensibilities, I suppose, but the truth is that my first record was signed to Terrible, a tiny label, and 4AD picked up that record—and for the most part, that operation is the same as any other major. They're still cutting the same type of deals. The only difference I saw was that you didn't get $60,000 to make a music video. They'd be like, "Can you make it for $5,000?" I famously used to complain all the time about how I could make a better music video for $500 than $5,000—that's how I felt at the time.

My switch from jumping to a major was about feeling how I'd been duped by being on an indie label. I thought it was about working with people who really cared about music and would foster suggestions and put you in touch with musicians who had integrity and lifted you up—business people who had creative ideas about how to push non-commercial, left-leaning artists, whatever you want to call it. When I showed up, it was just the same exact things I saw at the major label: A bunch of people older than you trying desperately to keep their job. You cannot have a generative environment where everyone's afraid of losing their job and making the wrong decision or supporting the wrong artist.

Honestly, indie, major, same exact thing, same exact experience. When you're in that 1% at a major label and they're truly showing up rewarding you with diamond rings and stuff—I think that does exist, and those people have this dramatic shift where they really feel what money can do. The major bought me out of my deal with the indie, though, and it was just more of the same. The people who were enthusiastic about the project wanted to show that they were there to support you, but it quickly became the same exact thing of, "You guys don't know what to do with this." There wasn't a lot of original ideas at the table, and nobody was excited. I don't always blame the other parties involved—I blame myself at times for whatever headspace I was in.

But the only shift I could really feel was off of a major to my own independent deal, working with InGroove for distribution. Now I feel the difference. Now I understand what it means to select every single person on the team, to look at budgets every week and decide how you're gonna spend money, to look at the ever-changing music industry and say, "OK, this is a fucking crazy mess. How do I fit into this?" Right now is the only time I've ever felt a difference.

Tell me about the process of putting your own independent deal together. As someone who runs a newsletter, I sometimes feel like everything's held together with tape—like, in the end, I'm just some jerkoff with a blog, which I'm also totally okay with.

I like the idea of everything being held together with tape. That's what indie really is. When you're doing it yourself, you have to make sure the mechanism works, and oftentimes you yourself don't know how it works. The thing to do is actually duct tape it, strap it on, and try it. It's a constant trying. I don't feel exactly that way, because I've put together a team of people who specialize in the things I don't do. I focus my energy around music and the visuals.

But what had to change is a certain type of consistency. I have a meeting on Monday and a meeting on Friday with two different types of people, and as much as I dread that sort of consistency with marketing and meetings—It's so not who I am—I'm now responsible to the art that I've made to give it that other energy. Not to change myself, but to show up and be present and care about the fact that I want to be a part of the music industry, sell music, and for people to hear my music. Being a part of the uglier part of the music industry on Mondays and Fridays feels like my responsibility, and that's what had to change. I had to be consistent about showing up and doing that. So that's four hours of my week, which isn't that bad.

But that's where it's at—taking that real responsibility. It's not fun, because it takes your artist's mind away from itself and gets yourself looking at Spotify numbers, whether you're getting reviews or not, and how it all fits together. That's enough to break anyone's spirit all the time. But I do feel like, if I'm going to have my own label and put music out on it—not just my own—I have to own up to it.

Your career started a few years before streaming really took hold in the music industry. How does that aspect work for your career now?

There's so much to think about. I try not to get myself too in the weeds about it. There's so many issues, right? There's the streaming model in terms of how it pays out to artists, which has major problems. There's the algorithm and how it's affected the sound and structure of what people make.

I love and hate some of that stuff, but what I love about it is that music has always modeled itself after the medium it's presented on. Music changed when vinyl went to cassette because of song lengths and what you could fit on a side. Music has always changed according to how we're listening to it, and I love that that relationship exists because it's quite beautiful if you think about it.

It's the same way I think about lamenting why no one goes to the movie theaters—and in L.A. right now, it's hard to find a movie theater to even go to, which is hilariously ironic in Hollywood. But you see the format had to change. It had to go to streaming and towards series and docudramas. Things had to change. I love when musicians and artists are forced to change because of the consumption habits of people. It allows us an opportunity to be innovative and respond to something that's actually happening, rather than make-believe.

I'm also a sentimental person and have my own of degree of nostalgia for starting to worry about how songs fit into the algorithm with what's working and what's not working. You want to be free of it, but you actually can't be. I'm not trying to focus too much on the scary part of computers selecting music, and I'm trying to let it help me innovate—or not, to let me be totally rebellious.

When's the last time you went out and heard music played in a place that wasn't your house?

I was at a party a few weeks ago that was the most turned-up party straight out of a movie that I've been to maybe ever in L.A. You really felt this pressure-cooker energy there. They were playing that Madonna song, "Caught Up," and the energy was very real. That's probably where I caught COVID. [Laughs] But it was worth it. Some old Uber driver said to me the other day, "I'm not gonna stop living to live."

Your career really kicked off in the early 2010s when the economic ecosystem around "indie"—especially in New York—was in a very specific place.

I'm going to try to do this without waxing poetic, because I really do believe we have to stay present and not live in the nostalgia of our past. But it was a really special moment, and I'm glad to have put out my first record during that time. I was saying to somebody the other day that what was beautiful about 2010 and 2011 was that, finally in New York at least—and I'm sure Chicago and L.A. people felt this too—but that bubble where whatever was happening in New York was the only thing that was happening didn't exist anymore.

In New York circa 2009, if it was guys in a band, it was some sort of Strokes derivative, and at your best you might sound a little like Fleetwood Mac. I'm obviously wildly generalizing—there was tons of electronic music, and[Burial's Untrue] was ahead of all of us. But there was a group of us in New York who came from a more punk, goth school of songwriting who got our hands on synthesizers and old gear—things we could afford, I bought my Juno for $600—and we started putting those obsessions into our music and, rather than making "cool person" music, it was quirky and nerdy and darker, moodier, more lush. In some ways, it was actually about a maximalist approach to music, filling the soundspace with little things and creating a world around your voice.

All of the sudden, you had a lot of interesting sounds all over the place. I always hated that it all got lumped in with the '80s and I still do. I listen to my first record and say, "This doesn't sound like any '80s record I've ever heard." I think that Black artists in general are always innovative due to a sense of necessity. You have a lot of R&B, rap, and trap music that's constantly innovating and doing beautiful things. But I think in some ways, indie rock's had its heart ripped out and it's barely flopping around on the floor.

In 2010 and 2011, we were all very curious, and there was a God's-honest innocence to making music and touring. All these festivals popping up everywhere, we had no idea they were a huge scam to the bands and the concertgoers, and that they fill bills leveraging massive acts—we were blind to all those things, so there was a certain type of ignorance that created a very special environment, and I'm very happy I put out my first record around that time.

When I interviewed you in 2015, you said you were "annoyingly sober."

I lost funding for a music video based on that interview.

I think you're talking about the Pitchfork interview from 2012.

OK. When we talked, I was very open about my lifestyle and partying at the time. I don't think you misquoted me, but I think something was taken out of context. In the interview it said something about "Abusing alcohol, women, blah blah blah." Some people took that as "I abuse women," which is absolutely not true. I don't think many people focused on that particular thing, but I did lose funding because of that quote. People said, "We're not in line with him."

Once that happened, I always wanted to clarify is that what I meant at the time was that there were times in my life where excess was either a thing that I thought someone who played was supposed to do, or there were dependencies that became crutches for me to play every day. Years later, I realized I was going through a lot of depression and anxiety attacks. I just wasn't addressing it. For me, I'd medicate, make it better for the tour, and do these big extremes to sort out how I was feeling.

But I always wanted to state for the record that my chemical abuses never led me to be abusive towards anyone—it was abuse towards myself. I was abusing all these things and living in excess because I didn't know how to deal with the simple idea of indie fame. I thought I could deal with it. I put on an air of maximum confidence to help me deal with it.

But the truth was, I was a mess and a disaster, and it was hard for me to adjust to some people knowing who I was. It was hard for me to get stopped on the L train. I thought it was easy, I thought I loved it. I have a much more balanced view of that now.

When I said I was "annoyingly sober," I had to make these hard right turns to gain footing, and that was also the point where I started taking Lexapro. It was the first time I took antidepressants, and at the time I felt like a sober zombie. I genuinely almost recoiled at the thought of partying. Now I realize that those are just extreme shifts I was engaging in to sort something out in myself.

One thing I've noticed throughout my own career is that drugs and alcohol are everywhere. There's always a drink being put in your hand, or lines getting cut up on a table. Substance abuse is everywhere in the music industry and media, as it's always been. Do you feel like attitudinal shifts are taking place in regards to that?

In 2011, it was still sort of taboo to talk about. That was my problem with the indie mentality. Everyone's so soft and polite about everything, and I wanted to be not that. I wanted to show my dirty laundry to everybody. I wasn't trying to get cool points, I was just being like, "Why isn't anyone talking about the fact that all we do on tour is drink every day?"

A bottle of whiskey is in the rider, it usually gets finished by the end of the night, and you do it six days a week. Because it gets normalized, all you have to ask yourself is, "Would I do this if I was just at my house?" Probably Friday-Saturday-Sunday, but not Monday-Tuesday-Wednesday-Thursday-Friday-Saturday. It's been a long time since I've been on a tour, and I've certainly slowed down, at times to a grinding halt, in terms of substances.

On the issue of mental health, when I was going through everything I put on an air of maximum confidence all the time. I was falling apart inside. There were times where I literally missed big paycheck gigs because I couldn't get on a plane due to complete breakdowns. It's important to say to people, "Everything is gonna go really well, and when it does, you're gonna pay attention to your mental health the least. It's not like people around you don't care about you, but if you're a charismatic person, you're probably not going to show signs you're falling apart inside."

That's the hard part. I can't blame myself and I can't blame anyone around me for not getting me the help I needed when I needed it. But once I started showing signs of falling apart...I literally made them stop a plane in Berlin on the runway when I was having a real breakdown. That's when the people around me were able to say, "Something's going on with you and we need to get you help."

And I did. I've been in therapy for a really long time, and I recommend it to anyone who has access. The problem is that most people don't have access, especially young Black artists. I certainly did not when I was a Pitchfork darling. I'm not a rich kid, I didn't come up with that kind of bread. It took me until I got to this point in my career where I could afford to take care of myself, and I wish the music industry would take that into consideration.