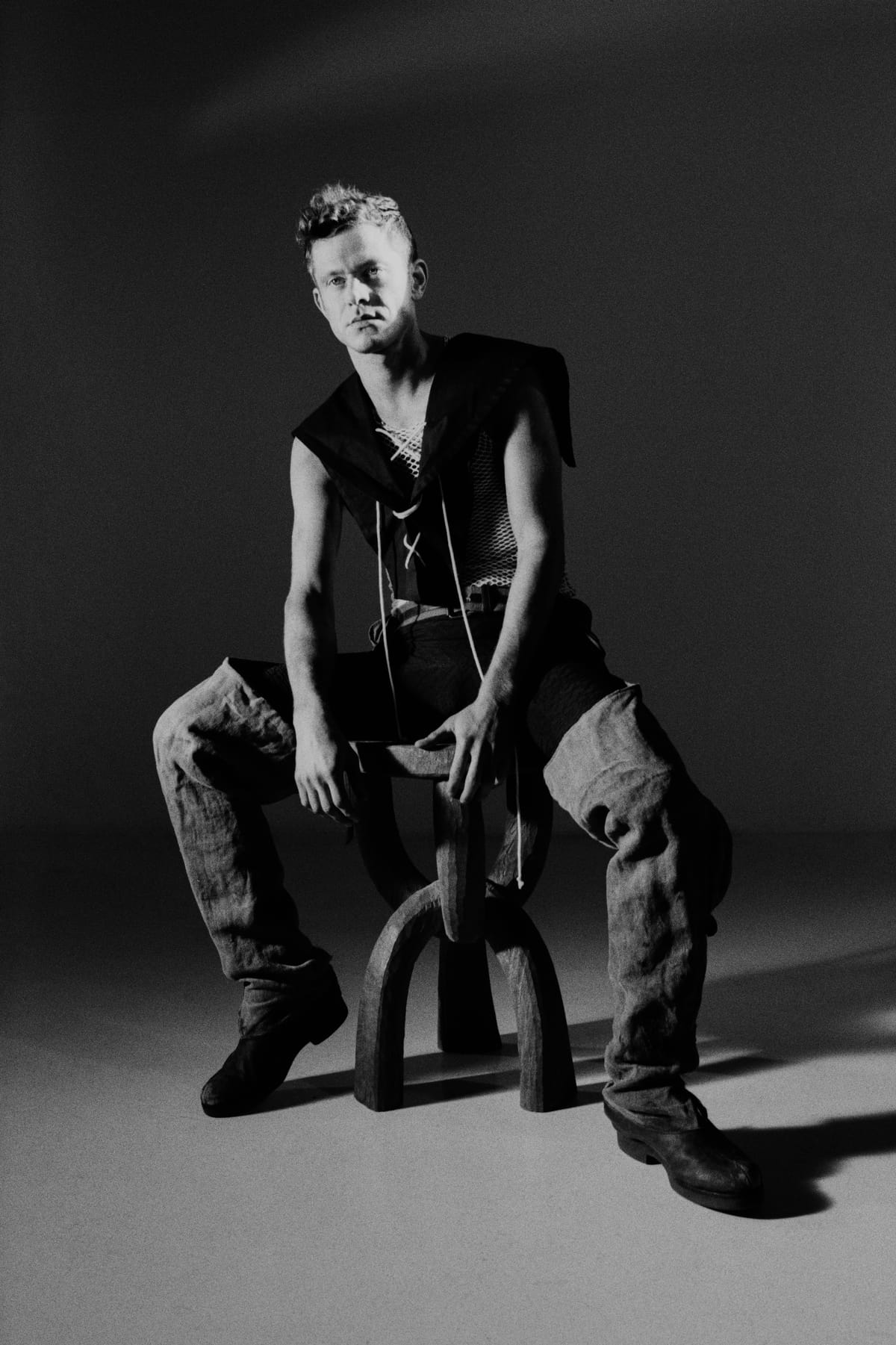

Perfume Genius on 10 Years of Too Bright, New Music, Video Games, and Embracing Showmanship

This is a free post from Larry Fitzmaurice's Last Donut of the Night newsletter. Paid subscribers get one or two email-only Baker's Dozens every week featuring music I've been listening to and some critical observations around it.

Real ones know I've been a Perfume Genius fan from the jump; I very positively reviewed the first two records for P4k, and soon after that he really broke through to a bigger audience with 2014's Too Bright, which just turned 10 and is in the process of having anniversary rung in with a series of concerts across the U.S. I've kept in contact with Mike since the Learning days and interviewed him for this newsletter back in 2020, and it was a real pleasure to have him back on the pub to talk all things Too Bright, some pop cultural fat-chewing, the next Perfume Genius record, and much more. Check it out:

The last time we talked was in the middle of lockdown. It was good to talk during that time. It was one of those like periods of time where I was like, "I definitely need to be reminded that people I know are alive."

A lot of people, in my view of them, did a really good job during COVID. I did not. So, any sort of contact I had with anybody was good.

What do you mean by "not doing a good job?"

It just really threw me. I don't even know if you want me to go into it right now.

You can go into it as much as you want.

It was just a darker time for me. I don't think I'd really been that depressed or confused as an adult, especially with all the music stuff. I'd been powering through and not being very present, because I thought it would be overwhelming, and I had so many things to do that made me nervous, you know what I mean? Shows, making music and stuff. So I was always um going, and then having that time to really feel present was not fun. I was feeling really mortal and having everything around me feel a lot more...I don't know. I was just available to looking at everyone and everything in my life as something that can leave, and that just threw me.

First of all, I think you might be overselling how many people did "a very good job." I think everybody was really fucked up during that time, and they're still extremely fucked up from that time.

I think that's true. Some people are just better at, when they're asked about it, they don't immediately jump to the truth. [Laughs] I was like, "Wait, I should do that." It seasons everything, too—it breaks a whole bunch of other ideas and safeties you have. I'm so avoidant, too. I've gotten really good at that, and I couldn't avoid certain things anymore.

I feel like I've been making people talk about the pandemic on this newsletter the entire time. Nobody wants to talk about it, but, like, this ruined all of our lives for, I don't know, forever? I feel like we should all be talking about this a little more, maybe!

Yeah. I have an aversion to it. If I'm watching a TV show and there's a mask, I'm like, "Come on." It's such a weird combination of needing to not think about it to feel okay and safe enough to like do your life—but not, like, a void. I mean, you can't really let anything dissipate or get over it until you actually truly think about it.

I felt that way about seeing masks in TV and movies for a minute there. What kind of brought me over the hump is when I saw Claire Denis' Both Sides of the Blade, which she filmed during COVID—and it very much looks like something that was filmed during COVID, where people are just, like, putting their masks on and taking them off indoors and outdoors, constantly. I was like, "Oh, this looks stupid. Suddenly, I feel a lot more comfortable seeing this depicted for some reason."

I don't think I've even heard of it. That's not the, what's her name, Margaret Qualley movie, the romance-y one?

That was Stars at Noon, which was similarly pandemic-y. I love her, but both of them are definitely, charitably, minor works. I honestly thought Stars at Noon was almost unwatchable, whereas Both Sides of the Blade is just a mediocre erotic thriller.

That sounds cool to me.

I mean, I'd recommend it. Even when she's off, she's really on.

Well, you know how something can really hit, and then it kind of doesn't. It's not landing like the good shit.

That's real. This upcoming Too Bright anniversary tour is your first outing in a few years, but you've been out there since COVID too. How has it felt to be back on the road again in general?

Honestly, I truly enjoy it a lot more than I ever have. When i first started, I was so nervous. It was enough for me to just get up there and do it at all, even if it was just sitting and looking down the whole time. It's changed a lot. I find so many things up there that I'm surprised by, and they feel really healing to me. Whether it's good or not, I don't have any idea sometimes. But it's really freeing. I have to kind of take a break from myself—the things that I normally think about—and go into something that's really free that I get excited about. I still get really nervous and everything, but every single time I walk on, something switches off—and I look forward to it.

Your performances, across the years, have mixed in showmanship with cards-on-the-table vulnerability. I saw your first NYC show way back when, and every time I've seen you since, you've leaned into the performative aspect of it more. Tell me more about that evolution for you, as well as what's gone into developing that onstage presence.

A lot of it is just practice, honestly. Everything happened really fast for me, so before my first shows as Perfume Genius, I wasn't in any other bands. I'd never sang in front of anybody. My first record was all demos I made at home. I'd never sang any of those songs in front of anybody. So my first shows were my first time singing in front of people and playing. Then, I wanted to keep pushing myself, so I kept intentionally trying to do that each tour—which I don't really do in my daily life.

I don't know, I got kind of obsessed with it. Somehow, I was able to be really nervous and do something anyway with performing. It wasn't like I just suddenly wasn't awkward or nervous—I dipped in and out of that, and I still do a lot. But I was easy with myself about it, being both things at once. I was also thinking about people I like watching. There's some weird hyper-presence where it's not like they're just finding something second by second—sometimes it's cool, sometimes it's not, sometimes it's really locked in, sometimes it isn't. I like seeing that back-and-forth, where something's in this crossfade of internal and external like.

At the same time I was touring with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, I was watching Karen O perform. I used to watch her videos before I toured just to remind myself what can be done, you know what I mean? I love watching her, and then I was watching her on that tour, and I thought about how I could see that crossfade. She's very performative, and she's a lot more in control than I am—but I also saw this internal thing with her, this in-and-out that was really exciting.

For what it's worth, in terms of control and presence, I think you're selling yourself a little short.

I don't know why i do that. But when I watch something back or listen to myself, I know when I wasn't in it, or when I was scared for that second. Even after we play shows, when we leave the stage, all of the band has a different idea of how good it was—and it's all based off of whether, like, if I sang good then it was a good show. It makes lose sight of the whole thing.

Too Bright has often been framed as a breakthrough after the first two records, but after revisiting it recently, I was actually surprised to find how close to those first two records it still sounds to me. Tell me about how you think it represents an artistic evolution for you, looking back.

I remember when I was writing the record, I was trying for a while to write things that didn't feel quite right to me, or just not new enough in ideas or directions in a way that was making me feel inspired. Then I wrote "I'm a Mother," which is basically just my demo on the record, and I was like, "This is something different." I was just going somewhere different energetically, and in the way that I was thinking about music and writing.

I was in the middle of changing when i wrote the record. I wasn't fully leaving all the things I had been doing right since then—even post-that record, it's all the same thing. But even though the quieter songs are the songs that feel a little more confessional—like I'm talking to someone, not like I'm going over my journal, or a memory, or trying to heal a past thing. It's a little more defiant or aggressive. even the quieter songs, to me. It's just all of those things, and I don't mind it being all of that stuff at once. But it definitely was intentional. I was trying to like push myself.

I remember the first shows around the album. I was like, "How am I going to do this?" I'd never even stood up at a show. Making the video for "Queen," I'd never...I was talking to [director Cody Critcheloe] about how nervous I was doing it. He didn't know that I was, but it was a lot more social than I was used to. I had to perform in that video, in front of people and stuff. It was really exciting, but really scary. Now, all of those things are...not second nature, I can just live alongside the nervousness better.

Tell me more about working with Cody, who always brings a distinctive perspective and visual energy to projects he directs.

I feel real kinship and trust with him, because of his ability to allow a bunch of things to be true at the same time—things being funny, and serious, and highbrow, but still demented. Not everybody finds all that in things that I make, or that he makes, but I feel like we both feel that way about each other. I could share any idea with him, and he'll understand the different layers of it, instead of just, like, the gayest one. I just think he's brilliant, honestly. He's a real visionary, and really dedicated.

My favorite artists are people that, no matter what, there's some core mission they have that they can never be like swayed from—some core charisma point of view that they have regardless. It's always there, and they're really protective of that. I think about that a lot when I'm writing—like, "Wait, is this influenced by what I think I should be doing, what other people hope I do, or what I actually want to do?" What makes me laugh, what makes me get excited? When I'm working with him, when I watch his stuff, I just feel excited and inspired, and leveled up in a way that's fun. Also, we just laugh all the time too, which I think is really important.

Tell me about your memories of working with Adrian Utley and John Parrish on this record.I haven't really talked to anybody who's worked with Adrian before, but I talked with Andrew Savage last year about working with John.

We made the second album in Bristol with Ali Chant, who produced this record with us too. So I had a relationship with him and that studio, and I'd never met Adrian—John played on the second record, just a couple of things. It was honestly really easy in a way that it hasn't been since. Everybody had the right amount of ego to get inspired and make choices that were their own, and were weird or off-center—but also enough to win other people over. We thought about things and came together, which is hard to do the more people you have in a room together. But there was just some shared sensibility—or maybe everybody just really understood what we wanted it to be like, or allowed it to be a bunch of different things.

I remember Adrian very casually just started playing a guitar with a rusty nail—but quietly, very [Mike slips into Jools Lebron impression] demure. [Laughs] Don't let me do that.

I won't.

It's hard, because it's like a song—it gets stuck in your head, you know what I mean? After the NHL posted a demure thing, I was like, "Okay, you can't do it anymore"—and that was, like, a week ago. But yeah, he was playing it with a rusty nail, but not like, "Check me out, I'm fucking going to town with the nail." John came in and played drums on "Grid," and he suddenly did like a double-time thing after the scream, and I got really activated. That was the first time that happened, and it happens to me all the time now. When I hear people play, I get really activated in a bunch of different areas that, honestly, maybe I shouldn't be—but I get so excited. It happens a lot with drumming. But little things and surprising decisions kept happening like that, and not because everybody was grinding and, like, doing coke or something. We were all hanging out, and the energy was calm, but the things we were doing were not, so it felt like a portal.

When you say that it felt easy in a way that things haven't since, I'm curious to hear you expand on that. How has following the creative spirit become different or more challenging as you've grown as an artist?

I mean, a lot of things have gotten better because of it. Even this last record—and I just made another one—it was very hard to do, but I honestly think it's really good. I think it's better because it was hard. I'm just way more self-aware. I have more of an understanding where, when I'm writing, I'm going to take it to the studio—and then, after the studio, I'm going to release it and I'm have all these meetings and go to tour.

Especially post-COVID, I can't really get into this delusional, magic place that I used to go when I was writing. I still go there, but it's more mortal. I was getting sick of writing all these songs that were these reach-y, desire-y, fantasy things—which, there's still some of those on the new record, but I realized that wasn't exciting to me. I wanted to write about my life and the people around me, and I realized that I had to because that was more exciting to me—but it was harder. Every lyric, every note, I was really obsessing over. Working in a way that like felt like work, I was just as obsessed and tireless as I normally am—but I read all my lyrics that I wrote, and listened to all the songs, and I was like, "Man, this is better." Whether that's true or not, I think it is, and I just feel really proud that I made something I actually like.

Every record, there's a couple of lyrics that I just threw in there. I don't hate them, but I just couldn't find the right thing, and I made something that's—not bad, but I didn't really get it. I don't feel like that about this new record. One line, I do, but everything else, I'm like, "Man, that's good."

Let's talk more about perception. You mentioned not wanting to do a certain type of song that maybe your broader fan base of listeners might be expecting from you at this point. Too Bright was a big moment for you in terms of growing the fan base itself. Talk about that experience, and the challenges that arise from being perceived or even boxed in due to expectations.

I mean, there's a lot. I make pop music, you know what I mean? And when we play shows, I want to play all the ones that everybody likes, because that's what I'd want to see. I can utilize that kind of pressure—it feels like fuel to me. But the older I get, the more strange it is to be forward-facing, having people watch me do something for like an hour, doing interviews for like a year and a half. And then I'm just home, and I have to go into a hole and then I'm supposed to crawl out of it with something better than the last time while somehow holding all this new information and all the information.

I always end up doing it, and I know that now, so I try not tofreak out during the hard parts. I think of the writer's block-y time as part of being—I always have to do that, but it doesn't make it feel better. I don't know. It's confusing, because sometimes I'm like, "I'm really proud, I'm really doing a good job," and then sometimes I'm like, "This is made-up." That's why I had a hard time writing in the beginning—I was like, "I'm just like making shit up, right? That's what it is, but why would I just do that?" For some reason, I didn't have the drive to do it until I figured out what the new mechanism was.

But, still, why would I do that? Why would anybody want to hear what I have to say? Even though it's basically my job, and I live off of it. But it's hard, when you're alone and in your head, to be generous, and I don't that like it has to be a skill, you know what I mean? I haven't drank for a long time, and gratitude is a big thing, but I just don't think I have that. I have to really intentionally do all of those nice things to myself and and have perspective, because it just doesn't organically happen to me, even though I wish it did.

You came up during the 2010s, which I think is being increasingly perceived as the last chance for a lot of people to build a career off of making art, for a while anyway. Maybe people weren't seeing the money, but there was a lot of it moving around regardless, and it resulted in preposterous situations that wouldn't be replicated today in any way. In the light of new attention around Too Bright, did you find yourself receiving any bizarre, extra-musical career requests or suggestions?

You know, I kind of had an untraditional thing—a bad deal, not with Matador, but with the first people that contacted me. They stole from me, and I didn't really leave them until No Shape came out. But I had "Normal Song" in a Honda commercial. That was just so crazy to me—the idea of being able to pay my rent and I didn't have to go work at the store.When we were on Letterman, that was the thing that's—I mean, I guess that's not, like, a wild thing to be able to do.

I mean, I was never on Letterman. It is a wild thing to be able to do.

But it wasn't some weird, out-of-left-field opportunity. But I was so nervous about that, for months. I knew that was something my parents would watch and go, "Oh, he actually is successful." My cousins were gonna watch that.

I probably will do anything, honestly. I was at a dinner with some other musician friends, and I was grilling them, "Would you do a commercial for Wal-Mart?" Most of them were so much better—more principled—than me. I'm kind of down.

Well, what people say and what people do are always two different things. I think it's easy to say, "I would never do that," and then when you see, like, a $40,000 check, you're like, "Oh shit. I might do this."

That's also a thing for sure. I do remember I had a couple of conversations about being in this movie ah where it would've been really explicit sex—I would've had to wear, like, prosthetics and stuff. I remember I was at my mom's house when I was having those conversations, and when I got off the phone, I was like, "What the fuck?" Even when I'd been doing music for a couple of years, I still could not have envisioned that. Of course, it didn't happen—I'm so glad—but I was like, "I guess I'll just be in this sex movie. Someone asks you to be in a movie, you go and you be in the movie.

I saw the recent interview with Chappell Roan where she talked about turning down film roles, which seems smart. I'm not going to name any names, but you do see the "indie musician-to-actor" pipeline take place where you're like, "You know, you don't need to do this. You can keep making music and get better at that instead."

Well, if you are going to do it, it's kind of like when people get famous off of TikTok or something, and then they have to play a big theater or like a stadium right away as their first show. I feel like if I just show up to like a movie set, I'm like, "Okay, I'll just wing it," which could be amazing. But, more than likely, you have to learn how to do everything. I'm probably the kind of person that would just do it though, honestly. I mean, if that sex movie panned out, I probably would've done it—but so many people that were involved literally got cancelled.

You mentioned finishing this upcoming record. I loved what you did for the National Anthem soundtrack, as well as your contribution to the latest Alice Boman record. With both of those songs, I was like, "Huh, this sounds a lot like Mike's early stuff." I'm curious if that's the direction you've been heading in again, or iff you've been taking a different direction sonically.

I remember reading my lyrics from the first couple records, which are probably my most favorite ones that I've ever written, honestly. I was like, "How do I go back?" I feel like I did that with this record, but in reality the lyrics are still way more abstract—but the place that they came from, and the things I was thinking about...even how hard it was, when I first started writing music, I was removed physically. I didn't have this somatic, "I feel so crazy" feeling that I end up having when I'm making music. I felt very measured, like an overseer or something—gathering information, and putting it together. That's how I wrote this record.

But it's not, like, a bunch of story songs about things that happened to me. I know what they're about, and honestly, it feels kind of way more vulnerable. But it's still pretty crazy. It's not a back-to-basics thing at all. How I was thinking and writing felt like that, but it doesn't sound like that. I will say that I played the record for a couple of friends, and all of them said it feels like the first records and the newer ones mixed together. But, to me, everything always sounds crazy, because I go in with a minimal idea, and that ends up crazy.

What video games have you been enjoying since we last spoke?

I was fully on a Souls kick for a long time. Elden Ring, I was on New Game+ 4 or something. I was obsessed with Dark Souls 3, Lies of P, Nioh 2.—anything really hard. But I think I've kind of burnt out on it.

I've never been a Soulslike person.

Really?

Yeah.

I love the spreadsheet-iness of it, the research. I love forums, all that stuff. Yeah. Those games consist of real-life thinking about the math while playing them. Also, I loved Baldur's Gate 3—my favorite game of all time, honestly. I'm gonna start replaying it. Did you play it?

No. This is very embarrassing, but ever since Diablo IV came out, it's just been so easy for me to zone out and play endlessly. I'll run a dungeon, do some chores, wash rinse repeat.

That's why i burnt out on the Soulslike thing. I wanted to just play a roguelike or something, where you're just in it right away.

I need to pull the trigger on Baldur's Gate 3 soon. This might be the recommendation that pushes me over the edge.

That's the thing though, because it requires some...you know when sometimes you can watch a movie that's like...what's that Tilda Swinton movie where she hears something weird?

Memoria.

Yeah, like, sometimes you can watch that, and sometimes you can't. With Diablo IV, sometimes you want that specific speed. Baldur's Gate, it's different. I wasn't ready to replay it, because you gotta talk to people, and then they talk back to you. Sometimes i don't want to talk to anybody—I just want to do stuff. But I think I'm more in a story zone now.

We talked about Ottessa Moshfegh back in 2020 too. Have you read Lapvona?

Yeah. I loved it.

Yeah, I loved it too.

It's my favorite one, for sure. I kind of hate her books, too, so it took me a little bit to realize that that meant I liked them. With books, I want bleak shit. I don't know why. But I loved Lapvona, and I didn't hate it. It's like the Suspiria remake, where maybe it's not a great movie, but everything is so in line with my tastes. Everything about that book was just so in line with things that I like, so it was a good combo.

What did you think of the Eileen film adaptation?

I liked it. It didn't match my experience reading the book. I fucking hated that book, but I thought about it for so long after I read it. I thought how much I hated it, you know what I mean? But the way I read that book, there wasn't a lot of cuntiness—and that movie was kind of cunty, which was amazing, but different.

Yeah, I liked the movie too, but it was just different than how I read the book. I don't know if she's somebody where I really need to see her stories adapted into films. Reading them is enough for me, and I say that with great admiration for her.

It would just be really hard to do a good job.