Patrick Wolf on Recovery, British Identity, and Crafting a Mental Museum

This is a free post from Larry Fitzmaurice's Last Donut of the Night newsletter. Paid subscribers get one or two email-only Baker's Dozens every week featuring music I've been listening to and some critical observations around it.

Patrick Wolf took 11 years off and returned back in 2023 with The Night Safari EP, and earlier this year he relased his proper follow-up to 2012's Sundark and Riverlight in the form of The Crying Neck—and it was a really striking return to form for an artist who made some seriously provocative and left-field art-pop in his initial run. As someone who was highly interested in Patrick's music back then and is very into how he's picked up where he's left off, it was a pure pleasure to hop on a call with him earlier this summer—prior to the release of his just-out Better or Worse EP and ahead of his upcoming US tour, which launches next month—and get into where he's been and where he's going. This was a really great and fascinating conversation to have, check it out:

The new record's great, and it's been out there for a minute now. Talk to me about how that feels.

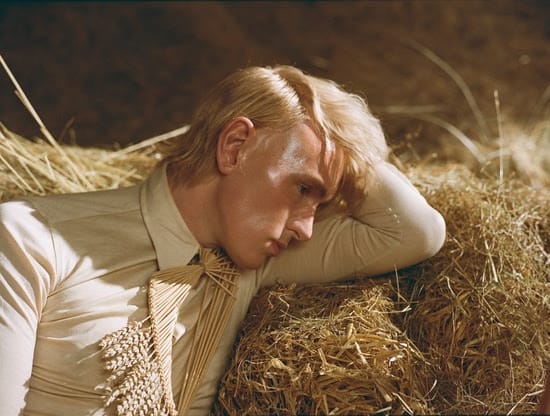

It is really useful that this American tour is coming up, and that we're about to announce some shows in March—because if that wasn't that, I'd just move on, really. I have a Patreon as well, and so much of it has been about going through the back catalog and re-analyzing lyrics and production. We're finally getting into Crying the Neck, and visually I'm even committing to this very specific type of blonde hair that's on the front cover of the album for the whole campaign.

But I want to move on. I want to shave my head and get onto the next album. That's signs of like health for me as an artist—burn the field and grow a new crop. I'm a professional enough now to follow through the whole campaign, and to actually see the value of it in other people's lives. I now need to show up for the album, take it on the road, and be an advocate and an ambassador for it. That takes the kind of professionalism that I'm not sure I used to have in the past.

The whole point is that this album is one of four. In a simple way, it's the four seasons of the year—but, for me, it's the Celtic wheel of the year. When I went into finishing this album, I already had the different parts of the wheel ready to start working on. So, I have in private moved on and started working on other things, but in terms of being public-facing, the duty for the album is to go out there and honor the fact that it's arrived in other people's lives.

The notion of being public-facing is interesting. Tell me more about the Patreon and what that experience has been like for you. If you look at when you were starting to put records out versus now, what is expected from artists when it comes to promoting a record is quite different.

It's an element of responsibility. In order to survive with music being your first job and your only income, you do have to be incredibly responsible. Now, I could never have done this with my behaviors of 2010, 2007—the recklessness of all that. Sobriety and my clean time has really dovetailed with setting up an infrastructure which gives me the freedom to be an artist.

In my classical training, when I was starting out—when I wasn't sure whether I wanted to be a composer or go into releasing albums —one of the big lessons was that we only find freedom through discipline. The contradiction is there, but in terms of what I've set up with the Patreon, this is all discipline—communications with people, posting once or twice a week, a monthly live stream, giving someone an infrastructure where they can live around and inside your work.

I don't know why, but the idea of community, that word—I'm allergic to it. I'm a loner. Community is really not my thing. But I guess I've accidentally invented this imaginary building that we all live in where we share objects and look at it. My psychotherapist—like, traditional, Freudian, Jungian psychotherapy—he introduced the idea during the period that I hadn't released anything for 10 years, he was like, "How about we see your your work as objects of value that we can put in a mental museum?" So I started the Patreon as the museum. My psychotherapist told me to find some value in it, so I have found freedom through this discipline.

But just the other day, I was actually thinking about this idea that the relationship with my supporters is...how do I put this...it's the right of the artist, the poet, or the visionary to disappear and to not be of service. To vanish, to go into a silent place and not be reachable, to find something to bring back to the world. That can be introspection, it can be a physical journey—but in this social media age, it's nearly impossible to carve that space out. I'm trying to find, as I go along with that space, how I can still go into the cave to find a little bit of treasure. But there's a responsibility to show up, and that discipline gives me the financial freedom to work. So there's a lot of balancing, and a lot to be conscious of, so that I maintain this equilibrium between being able to write and being able to support myself.

What was it like, in terms of mental preparation and emotional labor, to get back into the practice of being a public-facing musician over the last five years? Because I think you make a very good point with regards to the right of the artist disappear for a bit. I think a lot about Frank Ocean in that sense, where there have obviously been a lot of like specific demands on him from the public. D'Angelo is another example. I'm always like, "If this person's work is so special to you, maybe it's good to wait?"

My first thought is, if you look at Frank Ocean, these artists that you mentioned, they've all departed from a position of power, you know? Although I feel like I did too—I came out of a 10-year solid run from the age of 19 to 30 and exited stage left in a position of power, with people waiting to see what happened next. But when it got to year five or six, somebody basically said to me, "You're taking the piss now." And it ended up taking 11 years to come back to work.

Whatever that privilege is—let's call it a privilege—there were people waiting less and less every year, let's be honest. One year goes by, and another thousand people stop caring. I don't think I returned to work in a position of power, but I definitely left in one, and I had to be well aware of that. But I wouldn't change anything about that period away. I was actually very eager to come back in 2016, but I was in the grip of my addiction, and that confidence and ambition that I thought I was getting back was actually just the substances going through my body, which soon led to psychosis. I was floundering, and I needed everything that I could get in order to convince myself I was ready to work again, but around this time, this was entering a rock bottom period. It was really from that point when, a complete abstinence from everything mixed with the time that my mother died and the psychotherapy started, I was like, "Well ,it's going to be a lot longer until I can actually go to work, because I know that I need confidence, resilience, and a fundamental sense of self-worth."

Within recovery, if you're lucky, you have a sponsor who guides you through your early stages—and he basically said, "No Patrick Wolf for, at minimum, a year—until you've done the groundwork of being a human being." That was a lot of service—making tea and coffee, helping other addicts, doing a lot of non-showbiz stuff. These were real building blocks to the life and the career that I have ambition to hold for the next 10 or 20 years. I was aware that I was going to come back to work—back onto my path of releasing albums—but it wasn't going to happen until I was set for life and I had the skills to do so.

I really thought, for a long time—because of the way that I've been treated by the media in terms of really being othered as gay and, well, let's use the word flamboyant, in people's eyes and the clown element of the way a lot of the indie press kind of treated me—that I was a bit of a laughingstock. There was a lot of shame around that. It was a very different time to be other, really, in that period. There were very few Black, very few gay and lesbian people being held up to the spotlight within our world and music industry. And a lot of us were done with a little bit of, "wink wink, nudge nudge" and not taken seriously.

I was not prepared for that at that age. I was still so young. I always think The Magic Position came out when I was 27, but I was actually 23 or 24, and that was a lot for somebody at that age to be on primetime American TV, holding a toy gun, singing mental protest songs, and rolling around the floor on Conan O'Brien. It sounded like fun at the time, but I didn't have any roots. I didn't have anywhere to go home to. I was a very chaotic and quite troubled creature. I needed to go away to recalibrate and to become human again, and to come back into Wolf form.

One of the things that my psychotherapist asked me to do was type "Patrick Wolf" into Google—which I was terrified of doing, because I thought it would just be a load of people laughing, like, "Oh, remember this person? Oh my God!" I thought my career was like Carrie. It was those tiny little things, like daring to put my name into Google and actually realizing there were pieces about, "Oh, it's been 10 years since this album, let's deep dive into this record." Actually, people were celebrating my production, my work, my lyrics. People were actually honoring my work in completely the opposite way than I had thought. And that was when I thought, "Oh, okay, I think I've got this all wrong."

Did you see the Robbie Williams movie Better Man, by any chance?

No, I'm not a fan, no.

I mean, look, as an American, I'm not a fan of his music either, but I did find it very interesting in terms of what you're talking about.

Let's put it this way: I'm a fan of anyone that has the guts to go out there and put themselves in the public eye, in terms of being an entertainer. I support him, but growing up in this country, what he represented musically was almost the opposite, culturally, of what I and my friends—there was nothing of a counterculture about this man. It was the most "Southern Cross patriotic" kind of music. It was the other side of the track for us. I've been culturally allergic to his his position in our culture .

That makes a lot of sense to me. I think his music is terrible, and it seems like he's maybe gone into conspiracy theory land in the last couple of years. But I did find that biopic to be really fascinating in terms of addressing the critic inside one's head, especially in relation to addiction and recovery. But, obviously he's not countercultural in the slightest.

No, but I think he's one of those people who, late in life, thinks that they can rebrand as that—and no one ever considered you in that way. You can't suddenly go, "I represented something completely different at the time" because you decided that.

You had an interesting quote in the Dazed interview in 2023 that I want to talk about a little bit. You said, "I see some people that enter the public eye with their recovery, and it's almost like they're trying to sell people something." You were talking about the discomfort you felt at the time with discussing the details regarding your own experience with addiction and recovery. Personally, I quit drinking after the pandemic, and it was a pretty substantial decision that definitely rewired me over the last four and a half years—the way I live, act, think. But what you were saying in the interview resonated with me, because I think anybody who has been there knows that there's a point in which talking about it with other people who don't know what you're dealing with explicitly can feel exhausting. I've personally struggled with notions of self-justification whenever I talk about it with other people. I go through stages where, sometimes I'm down to talk about my experience with other people, and other times I'm like, "This is a small part of my life. I am more than this." When it comes to that part of that interview, I'm curious to hear you talk about your feelings two years on and how things have been for you when it comes to talking about your own recovery.

I mean, I have some so many more opinions about this. I got clean in London, and there's an element of—I mean, first of all, let's put it this way: Recovery is free. We have rehabilitation centers, and there's a small empire and a capitalist business built around it, which I'm sure helps people, but fundamentally, the fellowships of recovery were all set up as free organizations accessible to everybody—non-religious, but spiritual programs. You can be an absurdist, and that can be your god. We're talking about non-religious systems here, and not for profit. All these fundamental elements are so brilliant, democratic, and unelitist, and they're for everybody. That's the beauty of it.

I like to go about my way in terms of recovery. First of all, I understand that, everybody that gets a year clean or sober, it is a miraculous process for so many people—but it can give people God complexes. The Promethean aspect of stealing fire—of taking something that is free to all, a spiritual process, a relationship with nature—of capitalizing on it and trying to sell it to people, is something I will always be against, whether or not it's within organized religion.

Look, there's no activist left in me in terms of social media. I've done my time. I also feel that there are a lot more powerful ways to operate within this world outside of Meta or Twitter or whatever—that's a different conversation completely. But in terms of aesthetics, what my core values are—and I find this something so beautiful, so free, and so open to everybody—to come out and say that you own it and want to sell it to people is very dark-sided to me.

On the other hand, you have people who use recovery as PR—who come out and might still be using or drinking. That's not my problem. That's their own relationship. But people wield the new image of, "I'm sober, I'm clean" and fundamentally it's just a PR exercise—a way of, trying to change public opinion of themselves...there's just so many ways I've observed when it comes to being manipulated, repackaged, or exploited. I've been fascinated watching it all.

I was even adamant, when I got to five years clean and sober, of sharing that on social media. But I thought five years with an album, an EP, lots of touring—that was showing that recovery works you know. Therefore, it's attraction rather than promotion. I'm saying, "Look, I achieved all this, and I wouldn't have done it without making that very life-changing and hard first white flag of defeat of saying, 'I'm an addict, I'm an alcoholic, and everything changes from today.'" I don't want to criticize anybody's recovery, but I also want to make sure that, my God, there are fundamental principles to this. We're drowning in wellness. Our human traits are being diagnosed, re-diagnosed, sold medication or books about. We're being exploited all the time as human beings, and I think we can just bring it back to taking a long walk with an album and just being human.

But, again, am I contradicting here? Because I've got vinyls to sell, you know? That's why I'm really trying not to talk too much about recovery. I like the idea in the back of people's heads that my life changed when I got clean and sober. This is one of the great things that can happen. They've been to the shows where I could barely get past an hour, or I was almost fainting at the end of the show. They see the difference. I like the story to be in the back of people's heads, but it's not going to be the forefront of my narrative, and I also do not want the narrative of being a recovering addict to define me as a writer, either.

You've also talked about the loss and decay of national identity in Britain around this latest album. Did you see 28 Years Later?

Yes, I did see that.

That felt very much like a "loss and decay of national identity" movie.

I think that's probably what most Americans think England is like anyway, right? No phone reception, a lot of people wandering around trying to kill each other. I'm living on an island with no electricity, so I get it. In terms of subject matter in that film, one of the kinds of collective consciousness of Britain is that—and it was never talked about when I was younger, because there was still the shadow of empire, the afterglow of a tyrannical empire—but Britain being this global superpower, nobody ever talked about England being an island when I was growing up. It was always just this idea that we were still an empire—the commonwealth, the power of Britain.

I always loved pissing people off by saying, "I live on this island called Britain." People didn't want to acknowledge that it's an island, and I did notice the metaphor of the people being constricted on this small island space for what's left of England there. Then, of course, you have the Brexit metaphor of the closing down of the border, the isolationist attitude of England in the last three or four years, a slow progress into a quite fundamental cry for isolation, which still happens. It's happening even more today, after Brexit—a constant call for a pulling up of the drawbridge.

On my song "The Last of England," there's the lyric, "And by Mabon, were you dancing the broom by the light of the burning pier," with the burning pier representing cutting off the people left on the island—burning the thing that you can either leave or receive people from, the pulling up at the drawbridge of Britain.

That whole song is my observation that, since Brexit, there are two forms of radicalization. There's the people that fall back into trying to resurrect the corpse of the empirical England, and people that lean back into the power of Britain during World War II.

Where I live down in Kent, I can see France from the end of my road at the cliffs on a good day—and this was the link between the German warplanes. They would arrive over where I live. All around the coast are old concrete bunkers and relics and infrastructure from World War II. So I set the song in the ruins of England, which half of England—just to really go all in with the whole dividedness—went into a "two World Wars, one World Cup," the power of an England that doesn't exist anymore. Those are the people that are burning the piers down, who are returning to island mentality.

On the other side, for every Saint George's flag that goes up, there's a new folk artist that appears on social media who's gone through their local villages, found some old folk tradition, and have become a lino artist or an oil painter. It seems like there's a lot of people trying to connect with another side of England that's even more ancient—like, "If we can't be European, now is the time to define my identity. I'm gonna have to go far back and find my roots within folk culture."

Those are the two ways people have gone in the last six years—two limbs of the same rotten corpse. Then there's me in the middle, observing and existing. Not to be a centrist politically, but my return to work has been as purely out of observation—studying people, the rhythms of nature and of this country. So far, I love this position that I've found myself in.

Have you seen Eddington yet?

No, what is that?

It's the new Ari Aster movie. He did Hereditary, Midsommar. It's a neo-Western set in New Mexico during COVID. One of the things that it really does a great job of communicating is that, in America, political ideologies at this point are really just formed by the desire to mold one's image according to wherever the wind blows. That seems like an inexorable truth to me, and as somebody who thinks a lot about this stuff, it's been very interesting to have two movies in theaters in the last two months talking about respective national identities, or lack thereof. I recommend it.

Yeah, it sounds interesting. I'm really interested to travel around America this year, with this new relationship with myself as a writer. First of all, I'm flying into Vancouver and I'm driving—no tour manager, no sound engineer. I'm hiring a truck, filling it with merchant instruments, and driving all the way across America. The only flights I'm taking are to Vancouver and then back home from Washington, so I'm doing a two-month road trip. I can't wait to do some good observation and really take in what the rhythm of America is at the moment.

When was the last time you spent that length of time in America?

2015. I was trying to find management, manically. It was not a happy time for me at all. To be honest, I don't think I've ever been in California sober in my life, because I only went there when I was 20. I visited New York once when I was 13. As an adult, I've never been in America sober—like, literally. It's going to be wonderful to completely connect in a different, centered, and grounded way.

It's a whole new experience for me again, and there's some healing to do, because there's a lot of ghosts of past versions of myself that I've worked very hard to overcome and exorcise. When I went on the European tour, I'd turn up at a venue and be like, "Oh my God, this was that show that happened." I've done a lot of slow-making amends with audiences around the world, and a lot of them wouldn't even realize the difference—but it means something to me to be starting again on a completely different book. Gradually working my way across America in this way is going to be very healing for me.