Cocteau Twins' Simon Raymonde on Dream Pop, Looking Back, and Hope for the Kids

This is a free post from Larry Fitzmaurice's Last Donut of the Night newsletter. Paid subscribers get one or two email-only Baker's Dozens every week featuring music I've been listening to and some critical observations around it.

Aaaaaand we're just about at the halfway point through the holiday subscription sale, which will play out right up through New Years Day. It's 50% off monthly and annual subscriptions, as good of a deal as any. You can grab the monthly sale here, and the annual sale here. It's a great way to support a 100% independent publication.

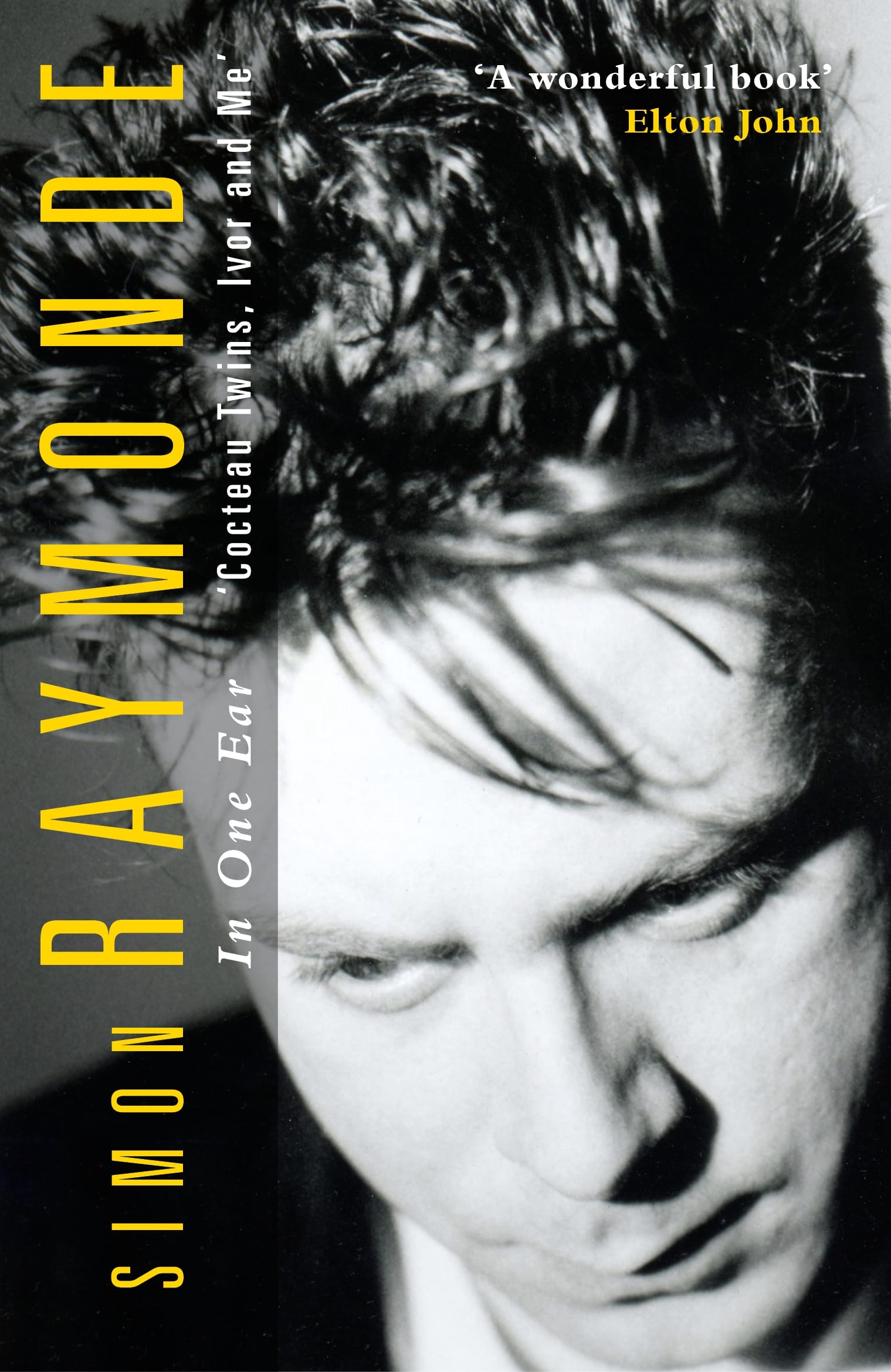

Let's get into it: Simon Raymonde is a legend in two games, from his contributions to Cocteau Twins (who are, obviously, one of the best bands of all time) to his founding of the long-running indie label Bella Union. He's had exactly the kind of life that would lend itself to a good book, and fittingly his recently-released memoir In One Ear: Cocteau Twins, Ivor, and Me is very engrossing when it comes to his own personal history as well as the ins-and-outs of running a label (and, of course, the details behind Cocteau Twins' own fraught history as a band). I was extremely honored to have Simon hop on a call last month to talk all things his book as well as a host of other subjects, and I was thoroughly unsurprised but nonetheless very pleased at how forthcoming and warm he was. Check it out:

I loved reading this memoir. Talk to me about how it came together in general.

I honestly didn't really ever have a plan to write a book. I'm not a massive fan of music autobiographies. I don't tend to go there very often. But I was talking with Warren Ellis, who I've worked with ever since I started the label back in the late '90s—he's been a part of Bella Union for 20-odd years. and he lived at Brighton up until maybe two or three years ago—and we were having coffee one day and started talking about his book Nina Simone's Gum, which I thought was such an incredible book. It was so unconventional. The way he'd approached it was quite interesting to me.

I'd been fanning off inquiries about writing a book for a long time. It's not really my kind of thing—I wasn't sure I'd know which way to go with it—but here I am. I was inspired by Warren and the fact that he initially tried a ghostwriter, but it was never right because itdidn't sound like his voice. When you've obviously got such great experiences, it's always going to be better coming from inside. So I set right in and saw if I could get anywhere with it. I wrote what I thought was the book, and I got a literary agent who was a friend of mine and said he would help me out and tell me what I needed to do—because, obviously, I don't know the first thing about writing a book.

He said, "Send me some stuff when you're done," so I finished what I thought was the book and he said, "Oh, this is really really good—that's probably the first three or four chapters." I was like, "I thought I was close to finishing it!" He went, "No, no, this is 30 000 words—you need 100,000." At that point, I realized this wasn't going to be a bunch of short anecdotes. If I was going to do this properly, I had to really research it. I had to dig deep and shut myself off from other things for a while, so that's what I did. I did what normal writers probably do, which is get properly stuck into it and don't stop until you've exhausted the whole thing. That's how I got to the end.

One thing I took away from this book in terms of your creative pursuits is that you seem to have a pretty solid work ethic, which is hard to come by.

I suppose I probably got that from from my dad. I hate giving up on something and not seeing it through, and I don't like losing. I'm really stubborn, and you could probably tell that from reading the book in those moments where the label could've gone under and I could've just given up—and there were moments where I was thinking, "Maybe I should." But there was always something that brought me back from the brink. I was like, "No, I'm not going to give up yet. I've worked so hard on this. It would be such a disappointment to give up on it right now."

Also, I'm quite a fidget. I don't know if it's ADHD, but I can't sit still. I always need to be doing something. I'm not very good with being like, "I'm gonna go take a break and not do anything for a couple of weeks." I can't do that. My mind is too active, and right now, with the way the world is, I find it so distressing if I get online and read about everything. I get too depressed about it. Working, for me, is actually a major distraction from real life.

This book opens and closes with you talking about the tumor that you have near your ear. How is your health these days in general?

Well, as we speak, my health is really not great, but that's got nothing to do with the tumor. I just had an operation a couple of weeks ago, and I'm recovering at home from that. I feel like I had a car crash, and my whole body aches—but that's not specific to the brain tumor. That seems fine. It's got to the point where the doctors are like, "You don't need to come back every six months for a scan." I think the next one's not for a couple of years. What I have is a benign tumor, but it's very slow-growing. Whilst they do MRI scans every year or so, the last one I had, it hadn't really grown at all.

I was 40 when I first was diagnosed with it, but it may well have been in there for 20 years, God only knows. It's not causing me any issues like I figured it might at some point, touch wood it doesn't in the future. I've not had any dizzy spells or stroke-like symptoms, which is one of the things you've got to watch out for in case other parts of your face and body start reacting to the tumor. I just can't hear anything in my right ear—that's never coming back, and it's something I've got used to. Being deaf in one ear, you'd think it'd be a massive hindrance to being a musician and an A&R, but I don't really find it as such. I've worked my way around it.

The most irritating thing about it is when I'm at the cinema with my wife and I've sat in the wrong seat, and I can't hear a word she's saying. If we're walking down the street, she could be talking to me five minutes before I realize what she's been saying. On a personal domestic side, it's probably more irritating than it is on a business side—because, with music, I don't think you need both ears, really.

Another thing I gleaned from this book is that you have quite a passion for film in general. Have you seen anything you've enjoyed recently?

I'm going with my wife tonight to see the new Guillermo del Toro, so I'm excited to see that. I know it's on Netflix next week, but we were like, "No, that has to be seen in the cinema." We love cinema, right? Whilst I'm sure we watch as much Netflix and stuff as everybody else does, going to the films...I still get the same excitement as I did when I was a kid. Going to the movies just seems special—getting your popcorn and your drink, sitting down, the lights go out, and the movie starts. There's something very magical about it. I don't know whether it's a nostalgic thing—a romantic arc back to those days when the cinemas used to be packed and people used to actually watch films.

We have a Cineworld card, which is like a subscription thing at the cinema. We pay a certain thing a month, and you can just go and see as many movies as you want. It's a big, posh, fancypants cinema with a load of things in the foyer and 10 movie cinemas. It's a really amazing space. We make ourselves go. We even went to see Fantastic Four. We were like, "Why are we even watching this?" But sometimes it's nice to get out of the house when you're doing music business all day. We both manage artists as well, and it can be quite overwhelming, how much time the music business takes away from your personal life. My wife manages Big Joanie, Divide and Dissolve, and Gina Birch from the Raincoats, and she's really busy. You could be getting texts at 11, 12 o'clock at night, and you're like, "Guys, we're on the other side of the world here and we're trying to go to bed." For the movies, we can actually turn our phones off. It's one of the last spaces now where you can really unplug and not feel bad about it.

There's a part in the book where you talk about hiding copies of Phil Collins' Hello, I Must Be Going! in the record store you worked at. Did you ever come around on Phil Collins' music?

[Laughs] A few people have said, "Oh, that was mean." But I was talking about a moment in time in my 20s. There was a period in my life where I just didn't like anybody or anything that wasn't in a punk band. You get very tribal about your music when you're a kid. I didn't like anything else. The charts, Phil Collins, pop—I was just taking a dig at all that, but it was the 20-something me taking a pop at him, not necessarily the the 63-year-old me, because I'm sure phil is an absolutely top guy. I don't listen to his music, and I don't own any of his records. Well, that's probably not fair, I probably do have a couple of Genesis records in the collection somewhere.

I also thought your observations about music videos back then were extremely interesting. There's been a lot of romanticizing when it comes to people figuring out how to make them. I just watched the Billy Joel documentary, and there's a whole bit about how he was initially resistant to them but ended up making the form work for him. But you talk about how the Cocteaus had the opposite situation, where it wasn't something that you guys ever really felt comfortable doing. Now music videos are seen as this lost art, where it's harder than ever to make an interesting one, let alone one that breaks through.

There's lots of different elements to that. Obviously, from the Cocteaus' point of view, appearing on TV or Top of the Pops or whatever—anything with the camera involved was something we were just not naturally drawn towards. We definitely felt a bit uncomfortable about it, because we didn't want to be in that world of being up on a pedestal. We were very anti-that. But looking at it from my perspective now, as a sort of record label guy, I see how important the visual aesthetic is to people. But it's gone from short films, short videos and music videos to chopping these things up into such tiny segments for the hope of appealing to the algorithm and short attention span people have for looking at things—whether it be on Instagram or YouTube.

I don't know whether we're feeding it, but we need to get away from that. We need to change our attitude to film because filmmakers need time to tell a story, and now you just cram everything into 15 seconds. I suppose this is a dilemma for parents who are bringing up kids that are not paying attention at school because all they're doing is scrolling from left to right and looking at their phones. Nobody's concentrating on anything. We've lost, as a society, that ability to sit down and watch a movie for three hours and enjoy it without thinking, "Oh my God, what about this, what about that."

It's all almost becoming a lost culture, films and music videos. There was a story being told within the form of the video. I was never an MTV follower, particularly, but there's been some incredible videos made over the years, and careers have been have been elevated because of it. I suppose you could say that with Lola Young. The way she's used the visuals with her music, she's super clever. You can't knock it, the way she's reinvented clips to her own benefit. But you can't just keep going from 20 seconds, to 15, to 10, to 5—and now 5 seconds is too much! That's where we're going, and I'm a bit bemused by the whole thing. But, I am 63. I'm not the target audience, so I have to remember that, too.

You mentioned being a label guy, and thought the portions of the book talking about Bella Union were really interesting. As somebody who thinks a lot about how the music industry changes, I have to imagine that you have some opinions on how things have shifted. We've definitely experienced a bit of hyper-acceleration in the last 10 years. We will need longer than we have to get into that, because my views on it are probably not all particularly pleasant. The music business has never been as complicated and as difficult for kids and young bands to navigate as it is now. On the other hand, you could just look at it like, "Well, it's fucking total anarchy out there, so who gives a fuck?" If one of you loves making music, go in a rehearsal room and make your songs together and go play shows. Who cares? It's great if bands are making music because, if they don't, they'll go insane.

I think all common sense has been lost, and that's not just on the label side—it's every part of the business. I look at all my friends, and they're now doing 10 things rather than one thing. No young musician I know is not doing five other jobs as well, and the fees that they get from shows are shocking—not even different, in terms of pounds, than they were back in the day when I was starting to make music. It's really depressing in one sense, but as I said earlier, you could look at that and go, "Well, let's blow the whole thing up." As long as you can make music and enjoy yourselves, then that surely has to be a good thing.

Sometimes it's good to put a full stop at the end of that sentence and not talk too much about, "Yes, but what about Spotify and how little they pay?" Well, yeah, I mean, get over it. It is what it is—it's absolute shit—but you can still make music, right? There's a lot of people in the world who cannot make music. We can't get territorial about these things. But I like to think music will survive, because people will always make it whatever their circumstances are, financially or economically. People will always still make music, and that has to be a plus.

If you're asking me to sum up the last 10 years, I'd say it's a massive shit show in terms of where it's gone. But when I think, "God, this is bleak"... one of my bands came over to the house the other day—a band from Denmark called Lowly, phenomenal group, never achieved the status they should have as yet, but they will maybe in time. They were over for a visit, and one of their kids was staying in the house with us. The kid was 14, and we were talking about music. He's very shy and didn't really open up much, but when we started talking about music, his eyes lit up. I said to him, "Where do you discover your music?" Because that's always interesting to me as a starting point for conversation.

This kid ran up to the bedroom and came back downstairs with his backpack, which had 30 CDs in it. I was like, "Oh, okay I was not expecting that." He said, "I love having my own little collection because there's no personality to Spotify. There's no reflection of me. If I listen to 10 songs that are on some playlist, it's not my playlist—it's someone else's. I want my own music, and I go into shops and pick up a bunch of CDs. I might not even know what they are, but I buy a few, sell a few, and I have my collection with me and I take it everywhere I go." I was like, "Oh man, that is inspiring." Because isn't that what we were all doing at that age as well?

We're thinking, "Oh no, the next generation—they've got no chance, we've lost the kids." Well, no we haven't, because they're rebelling against all this shit too. They're fed up with it. They want to have something in their record collection, on the wall, in a box in the corner of their bed set. I found that quite inspiring, because it made me remember what it was like, being that age and starting to collect music, and how important that was.

You mention near the end of the book that Cocteau Twins are more popular than ever. Dream pop, shoegaze, two genres that are always operating on some level in the background—but in the last couple of years, they do feel more prevalent than before. What have you observed about kind of this new wave of acts, and do you have any of your own cultural inferences as to why this is happening?

It's an absolutely fascinating topic. Obviously, Cocteau Twins hovering over this whole thing is fascinating to witness. We made this music 30-odd years ago, and to realize that the demographic of people that are listening to that music in 2025 is 15-to-25-year-old women—I mean, it's not solely them, but the largest demographic is that age group. That's, of course, mind-blowing to a 63-year-old man who's figured, "Who's going to be interested in that kind of music now?" Well, clearly a lot of people still are.

The band we've worked with since their first record, Beach House, they're a huge part of that game as well. Almost by accident, "Space Song" blew up on TikTok and suddenly went bananas—going from 30, 40 million streams to a billion and a half now, in the space of a couple of years, just because of TikTok. TikTok has obviously completely blown open this whole dream pop shoegaze world. I don't know whether it's because it's a sound that works really well—it's a bit cinematic, moody, and melancholic, and maybe kids that age need that sound. Maybe we've never never moved on from that sound. Kids have a lot of feelings at that age, 15 to 25, and the music being melancholic draws them in.

When I go see a Beach House show now...10 years ago, the audience was maybe not my age, but certainly 40 to 50. Now, it's 15-year-old girls screaming the moment Victoria walks onstage. That's quite beautiful to watch. So I'm a massive fan of it, even though there is a small part of me that feels like, "Come on guys, do something new. You don't just need to do this thing that we did and just rehash it. There must be something new on the horizon." Well, maybe there is and I just haven't discovered it. But for the most part, I'm absolutely thrilled by it, and not just because I actually have a half-decent standard of living now because of because of cocktails when the royalties start.