Alan Palomo on Humor, Filmmaking, the Music Industry, and Looking Back at Looking Back

This is a free post from Larry Fitzmaurice's Last Donut of the Night newsletter. Paid subscribers also get two Baker's Dozen playlists a week along with music criticism around the music in the playlist. If you've been a paid subscriber and have not been getting charged or receiving the Baker's Dozens, please reach out via larry.fitzmaurice@email.com so we can get you situated—it's been a thing since the migrations it turns out, it happens.

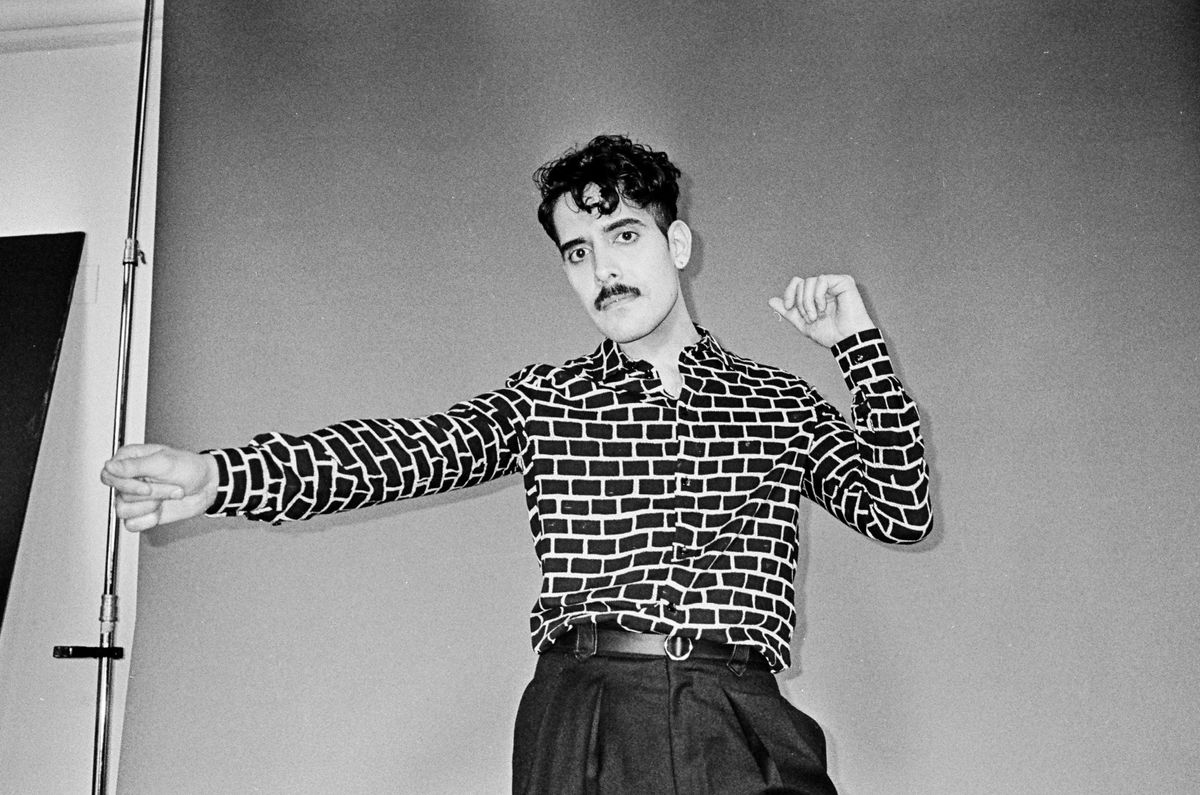

I've been a fan of Alan Palomo since the Neon Indian days, he really needs no introduction. I'd talked to him a long time ago for a site that no longer exists, and I had a great time chatting with him again around his fascinating new album World of Hassle and the nitty-gritty of being a musician these days:

I hear a personal, intimate nature to this record that sounds new to your music in general. Tell me more about that.

You could've called it Warts and All—I'm not hiding behind any effects on the vocals. That was a very deliberate choice, and part of what motivated that was that, with Neon Indian, I completed a nice trilogy of records. I said what I wanted to say with that specific set of influences, but for how much I labored the lyrics on there, they'd always fall on deaf ears. They were low in the mix, there was always some sort of distortion on reverb. I said to myself, "They know you can do something textural, they know you know how to use a synth. What haven't they heard from you?"

Throughout my 20s, I always loved stuff like Prefab Sprout that was very "Great American Songbook"-heavy—especially with them being British and fetishizing the concept of the American song. It always felt like such a noble pursuit, and obviously those records are incredible too. There was also stuff like the Blue Nile and Roxy Music's Avalon that never quite made it to the conversation in a satisfying way. So when I started writing these songs, I thought, "The one thing they haven't heard is your voice! So if it's front and center, you better get cracking on some lyrics."

It's not often that I get broken up with at a dinner and go home and write a song about it. It gave me more fair game to be—not directly biographical, because great songs, or at least my favorite songs, toe this line with all these added elements that make it feel like a real story, but the audience can still project their own parallels onto it. I was just ready to do that.

Also, it's such an '80s male rock cliché to leave your band in your 30s and have a crisis—hire the drummer for Weather Report or something. Obviously, Bryan Ferry is the king of that. When I was recording at Dan Lopatin's studio in New York while he was out in L.A. working on the Weeknd's stuff, he showed me this documentary about Sting called Bring on the Night about him going solo. He had this crisis in his mid-'30s, leaves the Police, and assembles a jazz band to practice in a 17th century chateau outside of Paris. It's this embarrassment of riches, and I wanted to play with the glut of that a bit. Not in an ironic way, because I love his records, and I love the fashion and the posturing. But there is an element of comedy, too.

I'm closer to who I'll be when I'm 50 than who I was when I was 20, so I wanted to assess the long run and think, "Who will I be then?" My brother always says, "You can't help you from 10 years ago—that guy is gone. But you can help you 10 years from now, so what will you want to be doing then?" Ironically, this would've been a great time to put out a Neon Indian record, with the rise of nostalgia for indie sleaze. But it was too delicious of a gamble not to take, to pivot in another direction and start doing something new.

Ego always gets in the way of it, too. You're watching Live Aid videos at 3 in the morning and thinking, "He was 35 when he did that?!" In short, it just felt like the right time to pivot and try something like that—to become another male rock cliché.

You mentioned humor, and I actually wanted ask you about where humor falls in terms of your work as well as what you find funny. What makes you laugh, and how does that intersect with your creative spirit?

I was raised on '90s stuff like Seinfeld. My humor is probaly more Gen X than millennial. I take the process of making music seriously, but not the product. If there's not a joy to be had in making it, you should just go back to school and do something else, because if you're gonna be miserable, you might as well be making more money. Every time I hit a wall with a record—the same thing happened with VEGA Intl. Night School—it's always a moment where I realize I'm taking it too serious. You're tapping into themes with a capital T, but any time you're making something that's too self-aware or grandiose is a time to walk away and try a different approach.

I was a fan of Leonard Cohen in college—who doesn't love "Suzanne"?—but for some reason I had completely snoozed on his I'm Your Man era. I was taken aback by this sudden sense of humor that had never really made its way to his work. It probably came from his making a record like the one with "Hallelujah" on it and getting shelved, for him to suddenly bring some of that acerbic wit towards irony and black comedy. There's a really great interview with him on German TV where he's talking to this sexologist—it's really bizarre, and I was taken aback at his ability to be so funny and slick and have these things to say. It was honestly inspiring.

I will say this: I've always looked like this, and this look at 18 was not a hot one. At 28 it made a little more sense, and at 38 I'll hit a good stride. I'm slowly working into an Elliott Gould Jewish zaddy, so Leonard Cohen would be good to aspire to be like at that age, and this is the blueprint to start doing that long-haul work.

Here's something I've had bouncing around my head since VEGA: Was Scritti Politti a formative influence for you? I know Gartside was a contemporary of some of the bands you mentioned before, and I've always been like, "I wonder if Alan is a fan of those Scritti records."

I am! You know what's funny? When I played my first show in London, one of the Scritti Politti dudes showed up and said, "You probably don't know my music." And the sad part was, at the time, I didn't. In this very British, self-deprecating, and lovely way, he was like, "I'm too old, you haven't heard my songs." But Cupid and Psyche '85...I have to be in a certain mood for it, because it's even more saccharine than Prefab, and that already turns a lot of people off of Prefab. But the production is undoubtedly genius.

The whole time I was making this album, I was trying to chase Thomas Dolby-type Fairlight PPG-style production with a ramen-version budget—early '90s digital synths, a Yamaha TG33. But the moment I finished the record, they announced a PPG reissue, and I was so pissed! [Laughs] I'd been chasing that sound for three years! But it'll be there for the next one.

Nostalgia is this perpetual thing at this point, we're always trapped in it now. What's your perspective?

The warm-and-fuzzies of YouTube's early days, where you find some Italo clip and feel nostalgic about a time you've never lived in, has dissipated as I get older. It's not the '80s, per se, that interests me. It has more to do with the genres that I've devoted my time to learning more and more about. Just when I think I've learned enough about one specific iteration of disco, Balearic, or sophisti-pop, I realize that in some other part of the world, something else was happening too. I like what I like, in that regard. The '90s really veered away from that style of songwriting and made way for other incredible things to happen, but I've moved away from having a personal nostalgia towards a specific palette—it's more about evoking certain moods.

Everyone's a product of their time. It's probably why Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson don't really make movies about the present. Why would you try to chase the next relevant thing? Once you've built a vocabulary that's yours, you can turn away from certain trappings or microgenres, but it's always gonna sound like you at the end of the day. What can make it sound fresh and interesting is this ongoing PhD that I'm trying to pursue in disco. First it was French, and then you're obsessed with Brazilian and boogie records. But, I mean, who knows! I wouldn't put it past myself to don a bucket hat and tight tank top with baggy jeans and write some song that sounds like Eiffel 65—but I doubt that's where you're going next.

I also doubt that's where you're going next. But something that is interesting to me about you is that you came up at this time where there was an immediate interest in music that was electronic and made in non-traditional studio settings. There was also an increased focus in quote-unquote indie music in general, and a lot of things have changed since then. How have you seen things play out within the long arc of your career thus far?

Obviously, I can't be mad at the internet, because even though it's spiraled into all these different directions and we're stuck in this echo chamber of taste—it's not even opinon-based anymore, it's just what the robots think you like—but I can't be mad, because in the beginning my music came out of one of those first microgenres as a result of music scenes no longer being dictated by geography, a common goal, or a group of friends. It was something that was curated by bloggers and journalists, and by fans too.

There was a certain eventuality about chillwave. It wasn't like any of us did some genius thing. Obviously, in hindsight now, "These millennials didn't get enough of the '80s to feel reconciled with it so they want to explore these aesthetics and be MPC wizards," and you also look at the stuff that was happening back then that was influencing me. You have bloghouse, and in high school you'd watch Ed Banger tour recaps and think, "Fuck, I wish I was partying!"

But on the other side, you'd have J Dilla's Ruff Draft. I DJ'd with [Washed Out's] Ernest Greene at the last Electronicon, and we talked about how Ruff Draft was a record we were talking about during that time. We were listening to bloghouse and French house, and then we were listening to lo-fi psychedelic indie like Ariel Pink, John Maus, Olivia Tremor Control, Magnetic Fields' Holiday—that was a big one for me. This merging of these two aesthetics, it felt like somebody was gonna do it, and I'm glad I got to be one of the first. The first, according to Carlos, but that's not for me to say.

I would say that, in this era, the main thing that changed—and I kept joking with friends that by the time I deliver this record, it's gonna be like the end of Interstellar where everyone is dying at the label. But what has changed about the landscape is that putting out a record now feels a little like we've slowly been chipping away at the control of what the artist and even the label has. What you think is the single might not actually be the single. What you pour all your money into, music video-wise, might just not pop off on some algorithmic whim. It really does feel like your record is this chip on a virtual craps table, frantically being gambled with by these bots. It feels out of your control in a way that kind of sucks.

I don't know how to make sense of it, because there's this increasing list of prerequisites and demands. They want you to be a pundit, a content creator, a tutor, a role model, a comedian, a commentator. As those things pile up, the returns by which you continue to make your living off of continue to diminish. The way I've always quantified success is, "Do I have the resources to make the things I want to make?" And maybe those ambitions grow! You wanna make a record on this sort of scale, or you wanna make a short film, or you wanna go for some sort of modest indie feature film. The byproducts of success—money, stability, all of that stuff—were always in the background.

But as you get older, you're also like, we're in the middle of the great American real estate swindle. Will I be able to buy a house with this next record? Will I be able to invest in property in the future? Are you essentially stuck in this middle-income middle-class job with no pension waiting for you at the end of it, no medical insurance? For the first time, you start sweating a little bit more. But the curmudgeon in me doesn't want to tour with anything less than a five-piece, because that's what the record sounds like and how it should be presented.

So it's this constant push-and-pull, reconciling with streaming and the raw deal that it dealt us a decade and a half ago when it was either that or piracy. And they're obviously never gonna change any time soon, because the returns are too high on their end. I'm still trying to navigate it, and I don't think I would do another five-song single rollout ahead of the record, because now I've noticed that the cycles are very front-heavy. The days of touring a record for 18 months are done—and that was literally a quote from the Spotify CEO. "You're just gonna have to be more prolific!" Which, also, side note, says the guy that's never tried to write a song in his fuckin' life. All that model is ensuring is that you're gonna have a lot more mediocre music and joyless collaborations from artists you love.

But also, you're cutting up the record into these smaller pieces and throwing it out there like chum until you have this last, larger piece and going, "Here you go!" That aspect I also do not like. So whether it works in this current model or not, I probably won't do that again. But at the same time, I'm an albums guy. I like longform. I love movies, I love a good long book, I like things that require a sitdown. My record will fly in the face of that current status quo, and I'm happy to do that, even if it's a detriment to me financially, because there's just so much noise out there. Why not just make things where you feel like they warrant their own existence?

Whether it's the best one or not, I'm happy with every record. The only record I ever felt like I did under pressure was the second one, and that's because I had management at the time who were like, "You gotta finish it. If you don't put it out this year, they're gonna forget about you." And that was a lie! So I don't really sweat that aspect of it these days. I also want to approach impending middle age with some degree of comfort.

You mentioned the financial aspect of all of this—tell me more about how that's played out for you. How have you stayed afloat?

Well, I sold my kidney on Reverb. [Laughs] Look, I didn't work for two years. I had this plan before the pandemic where I was like, "You have dual citizenship, maybe you can put a down payment on an apartment somewhere in Mexico." Two years of SBA loans and diminishing savings definitely did away with that. I was a DJ before I started making music, and that's become a constant in my life—not just out of financial necessity, but out of creative necessity. One hand washes the other, you need live shows to raise profiles for the DJ stuff and vice versa.

The live show for me has always been more of an investment, and as somebody who's seen too many concert films and wants to do a weird Tom Waits Big Time thing this time around, who knows! Hopefully the tour breaks even, but on the other side of it, I do have these other creative endeavors. I've been scoring a lot more, I've been directing a bit more. Part of what comes of that is this itch to be like, "Shit or get off the pot. You're 35. If you're gonna make something, let's do it soon, even if it's through very modest means." So I've been trying to figure out how to juggle the music side and the film side.

But I do think there's something to having a polyglot interest in art. People like a Miranda July or a Vincent Gallo, who were part of Gen X and were so ahead of the curve in terms of "You're gonna have to be a little of everything moving forward if you want to stay afloat." Thankfully, I have interests outside of sitting at the piano and writing songs. I did some commercial ad work. It's so funny—in L.A., all my friends in bands are slowly being like, composer, composer for indie films, composer for a documentary on Hulu or Amazon. Everyone's slowly playing that game, and I could fall into that, but the work I've done in the past few years in that regard—I wouldn't call it a means to an end, but it's more about an interest in learning more about the filmmaking process.

Any chance you can be on set or at the end of the assembly line in post-production is more opportunities to ask questions and see how the sauce gets made. With the last record, I decided that if I didn't have time to build a director's reel, I would do it on the label's dime and direct all the videos—which is what I've been doing, and Mom + Pop have been sweet enough to let me do that. Every time you're on set, it's time to learn. It's been cheaper than film school, I'll say that, and obviously I get a little more confident and comfortable with every video and short project.