Alan Braxe and DJ Falcon on Family, Skateboarding, Bloghouse, and Their Incredible Careers

This is a free newsletter installment. Paid subscribers also get a weekly Baker's Dozen playlist (along with some attendant criticism) on Fridays. If you don't want to or can't subscribe, I appreciate you reading—here's my Ko-Fi if you want to tip. All revenue from the newsletter is currently being donated to the National Network of Abortion Funds; we've raised over $750 so far.

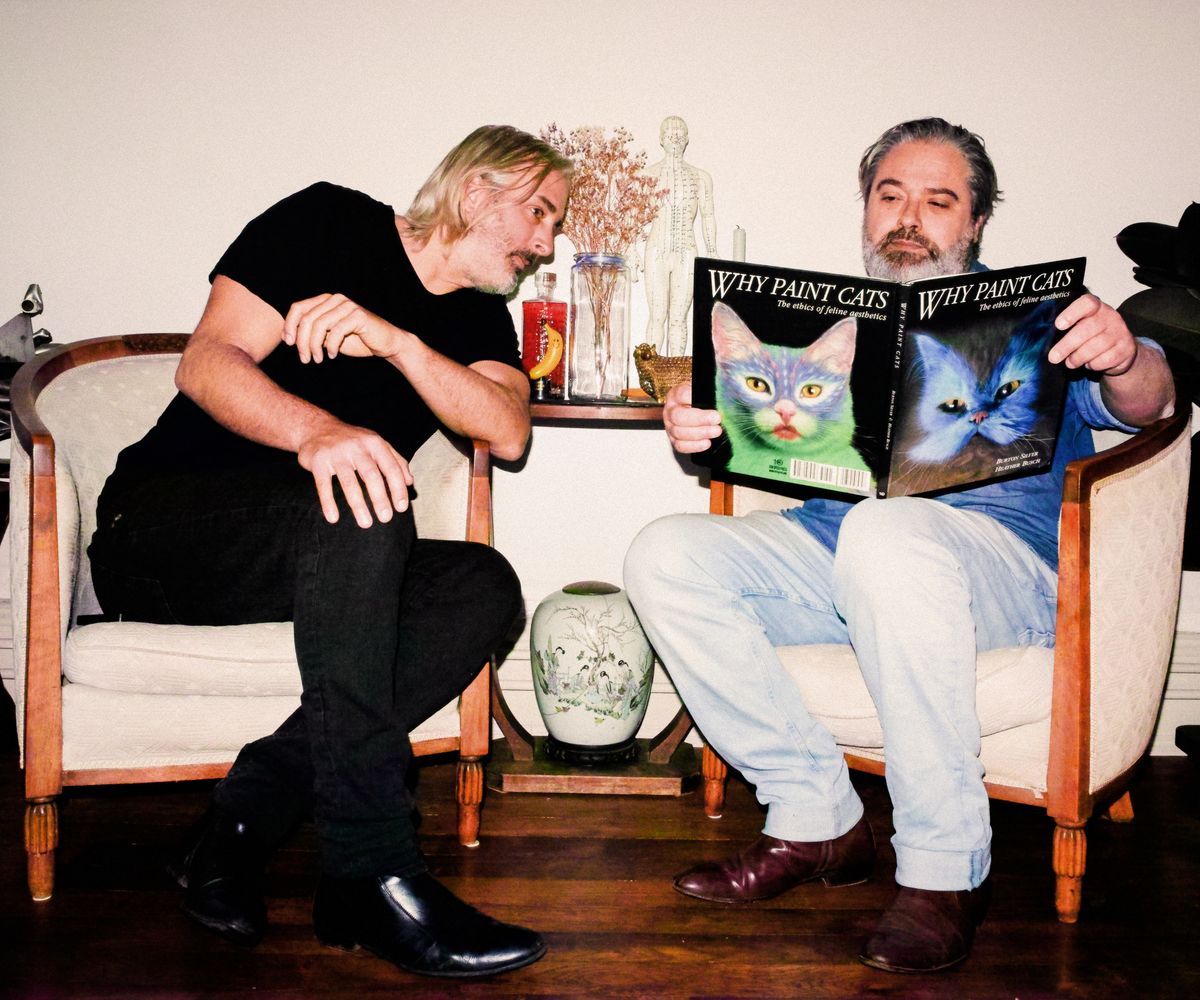

DJ Falcon (aka Stéphane Quême) and Alan Braxe are two legends of French house music (commonly referred to as "French Touch" by non-Gallic types). They're also cousins who never recorded anything together until quite recently, with their Step By Step EP on new Domino imprint Smugglers Way (featuring Friend of the Newsletter Noah Lennox, aka Animal Collective's Panda Bear) as their inaugural release. They have a full-length on the way too, but I thought it would be fun to dig into their past with the two of them and explore their rich history. They hopped on while Paris was in the middle of a brutal heat wave, but we had a good time anyway.

DJ Falcon, Hello My Name Is DJ Falcon EP [1999]

DJ FALCON: At the time, I was putting on a party. Pedro Winter was one of my best friends, we skateboarded together as kids. He was organizing parties way before me, but he had to stop because he just started working for Daft Punk. I took over his party, and I was also working as an A&R for Virgin—but just for one year. It wasn't something that was for me.

I'd just bought all the equipment six months before the EP was released. I got lucky, because I had advice from [Daft Punk's Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Cristo] and all my other friends about the equipment. All my DJ friends were big into the French Touch movement, so I had all the cool advice and all the cool equipment. This might be why it sounds good.

I'd never done music before. I was attracted by electronic music because you didn't need to be a musician. I just bought a sampler and all this equipment, and six months later Thomas was listening to my demos with my friend Pedro, and he proposed that I release them. I thought it was some kind of a joke. [Laughs]

You mentioned skateboarding, which is a culture that can sometimes be a gateway for getting into music. The two kind of go hand-in-hand sometimes.

I mean, skateboarding is so special. There's endless ways of expressing yourself, which is maybe similar to music. There's no other sport like it. Even with surfing, you're limited to maybe ten tricks. But skateboarding is unique. All my friends were sending skateboarding footage because we always got some good surprises. It's so creative. That endless thing is why it's similar to music. You're exploring new sounds, new equipment—it's like riding to a new spot. You let your creative mind find a line. There's a common element there.

Do you remember the earliest time you heard dance music? What was that experience like?

Coming from skateboarding, we were into Thrasher magazine—which is huge now, all the ten-year-old girls wear Thrasher t-shirts. At the time, it was the Bible for us. The magazine was pushing hip-hop, metal, and rock. So from the start, I was really open-minded to different types of music. Plus, I had two big sisters who were listening to Stevie Wonder and Prince.

A friend started throwing big rave parties in Paris in the '90s, and for us it was just a cool thing to do at the time. It was always a secret location, and it's appealing as a teenager when they tell you that it's forbidden. All that drama makes it exciting for a young kid. I was not the guy taking ecstasy and stuff. For some reason, I was having enough fun with all this. I'm not judging other people, it's fine.

There was always this big energy in the room, and I realized there was something cool about it. From the beginning, I enjoyed the repetition, and I found an interest in that type of music. When you go to a big rave, the DJ is just cutting the bass and bringing back so much energy, and it's so simple. For some reason, I was impressed by the simplicity and the size of it.

Together, "So Much Love to Give" [2002]

DJ Falcon: Before "So Much Love to Give," Thomas and I made the track called "Together"—that was our first collaboration. I was born the 2nd of January, and Thomas was born on the 3rd of January, so we first thought, "OK! Let's do this between our birthdays!" [Laughs] In the end, we had to wait a couple of months before we got into the studio.

Thomas was the first guy to enjoy my music, so after I released Hello My Name Is DJ Falcon, he was the first person to listen to every demo that I had. He noticed "Together," and we finished that one together, and with "So Much Love to Give" he came back with a sample he found and asked me if I wanted to collaborate. We did "Together" in the studio where they did Homework, and for "So Much Love to Give" he moved to a different apartment. Thomas is such a genius with sound that it was a no-brainer to record it with him.

Around this time, you started getting into DJing more. Tell me about the experience of DJing as opposed to being someone dancing in the crowd.

I really enjoy it. In everything I'm doing, I'm a passionate type of guy. When I'm doing something, I'm going no limit. But I also want to keep it as an amateur. I really want to feel like I don't feel burned out, so I try to keep it to two to three gigs per month so I can get excited. It's key for me to be as sincere as possible. I love traveling, so between traveling and doing a gig, I'm always smiling when I'm behind the decks.

Sometimes, you feel the magic, it's crazy. You have a really good response from the crowd. I've gotten more and more specialized playing with loops, and doing live stuff with Ableton. I was one of the first guys to use Ableton! It's more controlled than when other people DJ. Before that, I was using a sampler and a drum machine. So I'm really playing with those loops, and it's key when you have a good connection with the crowd. I can have multiple options to stack loops on top.

Over the years, I've created a setup where I'm really comfortable, and it's getting even more exciting to DJ since I have more control over what I'm playing. Sometimes, you get the magic moment, and you feel like people are going a bit crazy—and then I can play even more with that feeling. I really, really enjoy playing gigs.

The two of you are related, as we all know. What does family mean to the both of you?

DJ Falcon: We love each other! [Laughs] We're like an Italian family. When Alan produced his first vinyl, I didn't know it—but we're cool. We see each other a lot now, especially since we started making music. We have a lot of things in common. It's special. I think it's cool. Even sometimes, when we have a little bit of argument—which happens sometimes—it's a stronger relationship.

Alan Braxe: Since we're cousins, when there's a disagreement between us—which is on a daily basis [Laughs]—we always find a way to find conciliation, to agree. It's quite different because it's family. I'm the father of two kids, too, and I'm so happy. Family is something very specific, it's very different from friends. It's like being home—feeling safe and secure.

Alan Braxe, "Vertigo" [1997]

To me, there's two sides of French house as an American listener: There's the beatific, glowing style, and then the ruder, rougher stuff that takes cues from hip-hop. "Vertigo" sounds like part of that second side to me.

Alan Braxe: When I was 26 years old, I decided to give it a shot in the music business because I failed at university and had no specific options. I realized that I'd always been interested in music since I was a kid, so I was like, "OK, let's give it a chance." I bought some equipment and gave myself a challenge: Make one single within one year, and hopefully put it out on Thomas' Roulé label. So I bought some basic equipment, because it's more important about the state of mind that I was in when I made the track.

I made the track with an E-mu SP-12 sampler—it's very basic, super aggressive by itself, super limited. You can play it with just a few samples. The interaction between your thoughts and what you can do with the sound you're editing is quite immediate. It's just pure instinct.

So that's why the music sounds aggressive and resembles hip-hop—because this instrument was mainly used by hip-hop producers. The track was done in a few hours, super fast. It was a really interesting point in time: No computer, just a mixer and a compressor.

Alan Braxe and Fred Falke, "Rubicon" [2004]

Alan Braxe: Fred and I made "Rubicon" in my apartment. For the first time in my life, I was not single. I was in a long relationship with a girl who would end up being my wife. Fred was coming to my apartment on a daily basis, and we started working on the track on a Monday and we finished on a Sunday. Still no computer, just hardware switched on. It was quite obsolete equipment and we couldn't back anything up, so we were just playing so we didn't lose the music.

We knew the track would be released on my label, and the good thing about my label was there was no goal in terms of the style of music we wanted to do. We wanted to do a parody of '80s American music, so we had a lot of fun. Just pure fun.

This song was a bit of a breakthrough for you. Did you notice an uptick in interest around the time, in terms of the music you were making?

No, because it was still underground. Some people really loved it, and I got super positive feedback—but in the underground scene. We made a good video, though. We hoped that it could go further than pure underground, but it did not. It doesn't matter, the track is still sounding good, so.

I'm curious as to whether either of you have seen the Mia-Hansen Løve film Eden, which was largely about a semi-fictionalized history of French house music.

Alan Braxe: I haven't seen Eden. It's the whole story of the people I was hanging around at that time, and I don't want to see the movie because I don't want to be brought back to what I felt in the world I was evolving in at that time. It's too close for me.

DJ Falcon: I didn't see the movie either. I don't know why. Maybe I should. I had some weird feedback at the time, maybe I felt uncomfortable.

Alan Braxe: Because it's at the heart of what we've experienced—I guess, because I haven't seen the movie. But it's exactly what we've been through, so watching the movie could be a bit weird for us.

Daft Punk, "Contact" [2013]

Stephane, your work on this was kind of the culmination of your relationship with Thomas in general.

DJ Falcon: At the time of "So Much Love to Give," we started making a bit more music. It wasn't clear, but maybe we had the idea to do an album for the project. So we made some more demos, and this track was one of them. It was a sample that I found back in the day, and me and Thomas demoed it.

When we did "Together" and "So Much Love to Give," it was about showing the obsession of the loop, which makes sense. When it's really working, you get into a trance. But I thought that an album with those specific kind of tracks wasn't a good idea.

So we had a demo of "Contact" already, and around 2011 or 2012 I started wanting to release new music, because contrary to Alan, I didn't release a lot of music. I was more on the DJ side and traveling, and I'm also into photography—I'm working on a book right now. But I got excited about the idea of releasing new music again, and I got into modular synths. I asked Thomas, "What do we want to do with this track?" Thomas went back with Guy-Man and proposed that I collaborate with them for their album, and that's how it came about.

I'm curious to hear what both of you think has changed in French electronic music from when you started to now. What do you see as different? How do you think things have stayed the same?

DJ Falcon: There was the first wave with Laurent Garnier, Daft Punk, Cassius, Air, and Etienne de Crecy. In 2006-2007, the second wave started with Justice and the Ed Banger crew—Brodinski, some other guys. So there were two different waves from what they call "French Touch." We don't use the words "French Touch," it's the English press that started using that term. But I saw two different waves.

Alan Braxe: As Stephane mentioned, it's been quite a long time since Laurent Garnier started—almost 35 years ago. The equipment has changed, but there's some similarities between the early sound and the current sound. It's still quite simple.

Alan, I asked my social media followers if they had any specific remixes of yours that they wanted me to ask about, and no one had the same answer. You're as well known for your remixes as you are for your original tracks.

Alan Braxe: Me and Fred did a lot of remixes, and we've kept on doing them separately as well. What we learned together is to accept remixes where there's a vocal line, and where it's a different style of music than the one you make. Remixing techno is insurmountable. What can I do with it? Whereas when you have a vocal line, keeping the a cappella helps create more distance between the original track and a remix. You have more input.

Also, with remixes, you have a deadline. The label contacts you and they're checking in with you while you have two weeks to deliver the remix. It's good, because it's positive pressure. You don't have to overthink. Within two weeks, you have to deliver something, and then it's done. It's a good exercise for people like me. Personally, I tend to get lost on details and superficial aspects.

What does the term "bloghouse" mean to you guys? Have you ever come in contact with it?

Alan Braxe: Blog? Not really. Is it a term that was used during the MySpace era?

Yes, kind of a catchall for that era.

Alan Braxe: Yeah, not really, no. It's used to define house music from 2005-2008? Indie dance, indie disco stuff? I don't know much about it.

[Alan takes a minute to explain bloghouse in French to Stéphane]

I ask that because it's a term without much real meaning, but it is used to describe indie-adjacent dance music, including French house music. Over the last few years, people have constantly been saying "It's coming back." The two of you are returning with new music as well. Have either of you sensed a different energy in terms of interest in dance music as a cultural force?

DJ Falcon: COVID changed some stuff. All those DJs got stuck at home. I definitely think something changed. For us, we've been trying to do some demos and spend some time in studio over the last five, six, seven years. We definitely feel like we've been through a process that makes us more free about what we want to do. The first time we started doing music together in the studio, we got surprised that we'd never done club music before, because we were just trying to have fun and experiment.

But it took us a bit of time to process, and to be comfortable with the fact that we're not going in the direction where people are expecting us to go. In this COVID time, you can do what you want, it doesn't matter anymore. Just go with the flow and do what is natural to you. I think a lot of producers and artists felt the same way. So at the end of the day, I think it's a cool step. It brings a more natural way of thinking about things and doing stuff.

It was such a good surprise to see people receive "Step by Step," which is on the opposite side of the spectrum—we're talking 73 BPM. It was received super well, and they recognized some of our sound, too. That was such a big satisfaction for us. We're in a good direction, and it's good to connect with a new audience that enjoys it.

We could've had a lot of complaints—"OK, what's going on, where's the club tracks, where's the remixes?"—and audiences sometimes expect you to repeat what you've done in the past. It's like the McDonald's concept. But even the audience did the work in their head, and they're receptive to something new. I think it's a good time to make music right now.

Alan Braxe: I started making music quite a long time ago—I'm 50 years old now, I started 25 years ago. What I remember from the early days is that it was a very good feeling, and I had no idea what I was doing. I was just making music with no preconceived ideas. But years after years, you start to think, "Should I stick to the stereotypes of electronic and house music?" Maybe ten years ago, I was forcing myself to make four-to-the-floor tracks.

As Stephane said, it's weird because the COVID time was not fun, but it was good for us to get laid back and realize that none of this is important. It's just about making music and enjoying what we do, and not worrying about whether it'll fit in the dance or indie-pop fields or whatever. If we start to think about that, we are lost, because it stops all inspiration. You have to let go and find freedom in your head.