2013: The Year Everything Changed, Part 5

This is the fifth installment of a series of essays about how 2013 marked the point in which popular music and the culture around it changed forever. You can read the first four installments here, here, here, and here. The next installment will come on Tuesday, October 13, and it’ll (tentatively) be about Kanye West’s Yeezus.

As I mentioned in the first installment of this essay series, a few artists who were long-dormant came back in 2013. British electronic duo Boards of Canada, a group that’s long evoked mysticism through their relative anonymity as well as their deeply influential catalog of trippy, shapeshifting grooves, returned after eight years of silence with the creeping horror-soundtrack sounds of Tomorrow’s Harvest. My Bloody Valentine—a group that’s also long evoked mysticism through the mythology-building impact of their classic 1991 album Loveless—broke a 21-year-silence with the titanic and thrilling m b v.

We often refer to events like these—specifically, new missives from musicians who are more often known for their inactivity than anything else—as “comebacks,” a term that sometimes feels more wrong than right when applied to these situations. In BoC’s case, the notion of a comeback is in the eye of the beholder; the sylvan guitars of 2005’s The Campfire Headphase didn’t receive the same earth-shattering reception of the duo’s first two classic releases, 1998’s Music Has the Right to Children and 2002’s Geodaddi—but that record could hardly be termed a disappointment or failure, either. As for m b v? What was there to come back from at that point, other than years of updates from bandleader Kevin Shields that never came to fruition?

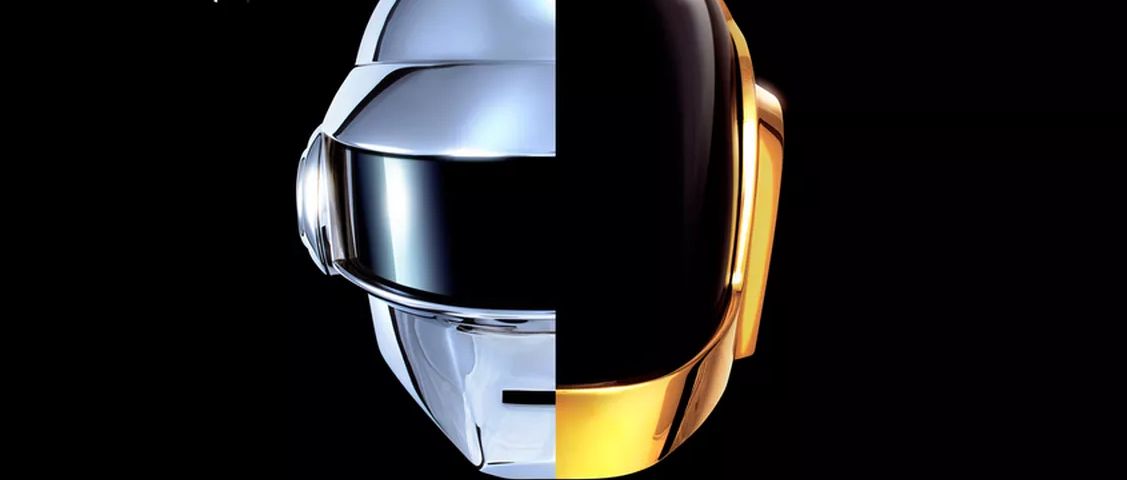

The question of whether the word “comeback” applies to every long-awaited return certainly can be asked of the biggest “comeback” of 2013: Daft Punk’s massive, award-winning Random Access Memories. Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Cristo’s fourth studio album, under a certain light, could be seen as something to a return to form for the legendary dance music duo. Its most immediate predecessor, 2005’s Human After All, was considered one of the 2000s’ greatest disappointments following the brain-exploding pop of their 2001 classic Discovery, and the pair’s soundtrack to Tron: Legacy was about as remarkable as the film itself.

Despite these perceived missteps (and, to be clear, both earned the reputation they garnered), Daft Punk had plenty of cultural capital to trade off. Discovery and its arguably-even-more-classic predecessor Homework from 1997—one of dance music’s great debut albums in a genre where the concept of “great albums” is itself a scarcity—are two documents that seem to be re-discovered by every successive generation of technological dreamers in love with Black house music and buzzsaw-like Gallic brashness. And most of the bad feelings surrounding Human After All were washed away by Alive 2007, an electrifying tour document capturing the iconic “pyramid shows” from that year. (Side note: I skipped out on the NYC date to see an acoustic Hold Steady set at Battery Park. I deeply, deeply regret the error.)

Daft Punk’s legend had grown in the years since Alive 2007, to the point where new music from the duo was feverishly awaited in the manner that one might look forward to, say, a new Star Wars movie. The robots were very much aware of this, too. “Our fans tend to throw themselves into the breach, or try to fill the empty spaces,” Daft Punk’s manager Paul Hahn told The Wall Street Journal in the lead-up to the album’s release, reflecting the fact that Daft Punk have long been maestros of their own well-deserved hype dating back to their demand for retaining quasi-anonymity when signing to Virgin pre-Homework. (If you’re interested, I went long on Homework for Pitchfork’s excellent Sunday Review series back in 2018.)

Daft Punk weren’t even the only enigmatic electronic duo to engage in an excitement-building promotional campaign in 2013. Let’s go back to Boards of Canada for a second, who teased Tomorrow’s Harvest with a series of six-digit codes released through TV advertisements, cryptic YouTubes, and a Record Store Day release that, when all combined, revealed information about the album itself.

The Random Access Memories campaign, however, was a supernova to the shooting star that was Tomorrow’s Harvest. There were Saturday Night Live advertisements, myriad billboards, a series of documentary videos that featured interviews with the album’s many collaborators—and, most memorably, a commercial teasing the Pharrell Williams and Nile Rodgers collaboration “Get Lucky” that aired on the big screens of that year’s installment of Coachella. No expense was spared—and why bother sparing expenses on a major-label budget?

By every conceivable measure, Random Access Memories was a success. It topped almost every conceivable global chart on the week of release and has since gone platinum in the U.S.; “Get Lucky” took home Record of the Year at the Grammys, while the album itself won the night’s big prize in Album of the Year. The critical acclaim was unanimous, the album’s contents having justified the anticipation and excitement that had been building up for so long.

What feels like forever ago but was actually a little under 18 months previous to this date, I Tweeted the following:

We’ve all gotten enough distance from the last Daft Punk album to admit that it sucked, rightJune 8, 2019

The internet, as it often does, lost their minds about this. Twitter decided to make it a Moment, presumably because amplifying things I Tweet while playing Tom Clancy’s The Division 2 in the middle of the night is more important than banning users who are making death threats against women. Some agreed, some didn’t, it’s all very whatever in the rearview. My critical stance still stands, though. I don’t think Random Access Memories is very good or interesting.

Daft Punk have long traded on nostalgia—Homework is a literal love letter to the Black originators of dance music, while the strident tracks on Human After All are essentially Kraftwerk homages filtered through an Ed Banger lens—but Random Access Memories, to me, represents a total immersion in looking back to the point where forward motion doesn’t exist. It’s didactic in a commercial sense, like an Epcot ride that mostly exists to sell you on the power and capacity for change that a corporation like AT&T could provide. It’s music in memoir form without any personality, akin to being shown someone’s record collection as “the music of my life” without getting any real sense of what made that life worth leading.

Of course, my own personal distaste for what I consider Daft Punk’s second-worst album doesn’t matter in the slightest—but my critical bias can’t help but make me think that what people loved about Random Access Memories was not the experience of listening to the album, but the experience of getting excited about the experience of listening to the album.

And the anticipation that Daft Punk so deftly stoked has become part and parcel of so many big-ticket music releases since. Album release campaigns have become longer than ever, stretching over a few months’ time or more; not even the instant impact of the surprise release that Beyoncé’s self-titled masterpiece would have later in 2013 (trust me, we’ll get to that one later) could slow the elaborate tease that has become album release campaigns from becoming a major facet of the pop music experience. Arguably, pop music has become more exhausting due to this trend, and the fact that Daft Punk were able to make it magical in the moment does speak to their continued existence as cultural vanguards, something that not even a bad album could make me deny.