2013: The Year That Everything Changed, Part 1

There’s no such thing as a bad year for music. Plenty of good music comes out every year, whether it’s shoved in your face or buried in the crevices for you to find yourself. But if you’re the type of person who spends every 12 calendar months listening to hundreds upon hundreds of albums, EPs, and whatever else is considered a “project” these days, you’ve likely developed a sort of internal shorthand of what are considered “good” and “bad” years in music. (If you spoke with me personally somewhere in the 2014-2016 period, you probably heard me insist at least once that 2014 was a “bad” year for music—a claim I have not yet re-evaluated and, the declarative nature of this paragraph’s first sentence aside, will have to stand by for posterity’s sake.)

Qualitative measures aside, there is such a thing as particularly impactful years for music—years in which the music released and the decisions made by musicians would influence other artists, the music industry, the music press, popular culture, and the world at large. If you’re going by decade, the 2010s had a few of these years: 2010 marked the point of arrival for decade-defining pop stars like Drake, Nicki Minaj, and Janelle Monaé, while 2011 served as the main-stage introduction for James Blake, the Odd Future collective, and Lana Del Rey—all of which would go on to define various musical and cultural trends for the rest of the decade (and, likely, beyond).

With era-defining releases from Kanye West, A Tribe Called Quest, Solange, Frank Ocean, Rihanna, and Beyoncé, 2016 was a supernova of a year for popular music in a way that stands in opposition to how 2016 will likely be remembered by most people in society. But more than any other year in the 2010s, 2013 was easily the most influential year in popular music—a year in which everything changed, from the nature of how music itself was released to how it was subsequently covered by the music press.

In terms of notable releases alone, looking back at 2013’s lineup can be dizzying—as someone who actively covered new music around this time, looking back for this essay even surprised me once or twice regarding things I’d not directly placed within the year itself. There were incredible and obtuse albums from the Knife and the Flaming Lips, the former’s Shaking the Habitual acting as the influential electronic act’s swan song and the latter’s The Terror marking the last time the band was interesting at all.

Fuck Buttons’ Slow Focus found the British duo adding hip-hop’s low end to their hyperspeed noise-techno approach; California metal act Deafheaven’s second album Sunbather similarly combined black metal’s searing roar with the gauzy blur of shoegaze and acted as an early signal of the total collapse in genre that would take place across all visible levels of popular music throughout the rest of the 2010s.

(Ironically, the 1975—who, barely a year into this new decade, continue their run as one of the most sonically adventurous pop-rock bands in existence—made their initial bow in 2013 with their self-titled debut, a sleek and almost uniformly emo-indebted album that failed to catch on with most critics.)

Trend-wise, there was plenty to spot within 2013’s wilds. CHVRCHES’ brilliant debut The Bones of What You Believe and Tegan and Sara’s spiky, effervescent seventh album Heartthrob marked the point of total inflection when it came to synth-pop becoming the predominant sound in indie. (My usual reminder here that “indie” is a marketing term and means nothing in terms of real ethos; both Chvrches and Tegan and Sara’s politics are certainly indie-inclined. Their major-label-signed statuses at this time, not so much.)

Rhye’s smooth, soporific debut Woman cemented the end of one trend—the “anonymous artist,” a cheap post-Weeknd conceit embraced by artists like Rhye members Mike Milosh and Robin Hannibal—and gestured towards R&B’s ascension as indie’s other predominant sound, all but signaling the disappearance of the guitar-driven trappings of indie rock that would be hotly debated for the decade’s remainder.

EDM, which was on an initial wane of public fascination around this time, finally got its torch song with Major Lazer’s breezy and endlessly remixed Amber Coffman duet “Get Free”; British duo Disclosure’s debut LP Settle, a freewheeling and studied recreation of the sonic tics that make up house music and UK Garage, effectively joined “Get Free” in offering a softer-sounding and less aggressive (but no less white) variant to the bro-tastic bass-face variants that made up commercially successful dance music. Swedish duo Icona Pop’s debut This Is…Icona Pop represented a more direct fusion of EDM’s fist-pump tendencies and non-masculine concerns, arriving a little too late to claim any real influence on either trend but remaining an enjoyable footnote regardless.

(Speaking of footnotes: it seems worth mentioning that Settle, beyond ushering in a glut of caffeine-free house-pop acts that still make minor waves to this day, also arguably led to the sedated and dialed-down dance-pop of artists like Kygo and the Chainsmokers, the latter of which having found a way to transplant EDM’s rampantly misogynistic culture while still lowering the volume to fit a bit better on adult contemporary playlists.)

It’s more than worth mentioning that two legendary and highly influential groups who’d long been missing in action—My Bloody Valentine and Boards of Canada—also returned in 2013 with albums that reinforced their legacies as musical innovators while also introducing new wrinkles to their since-familiar modes of play.

If releases like m b v and Tomorrow’s Harvest seem occasionally forgotten in conversations like these, it’s purely incidental and owing to the practical explosion of debut or breakout releases in 2013—a positively stacked freshman-ish class that included Chance the Rapper, Charli XCX, Run the Jewels, Earl Sweatshirt, HAIM, and Ariana Grande—that set the table for who would become some of the most celebrated present-day artists in popular culture. (If you’ve found yourself surprised by the number of emo and pop-punk-adjacent acts that have made up indie rock’s framework over the last three years, consider 2013 a locus point for this phenomenon, as two influential acts from that sphere—PUP and The World Is a Beautiful Place and I Want to Die) also released their debuts during that time.)

As far as pop’s biggest and brightest lights, there were a few misfires that also proved instructive when it came to the course that pop music was going down for the rest of the 2010s. JAY-Z’s derided-upon-impact Magna Carta Holy Grail embraced a slightly left-of-center (right-of-center?) release strategy by coming out first through an app exclusively for Samsung mobile customers, four days before the album saw a wider release. The strategy was seen as a failure to learn from, but the lessons went unheeded: a year later, U2 would notoriously force-release their Songs of Innocence on over 500 million iTunes accounts, a promotional blunder that far out-shadowed JAY-Z’s.

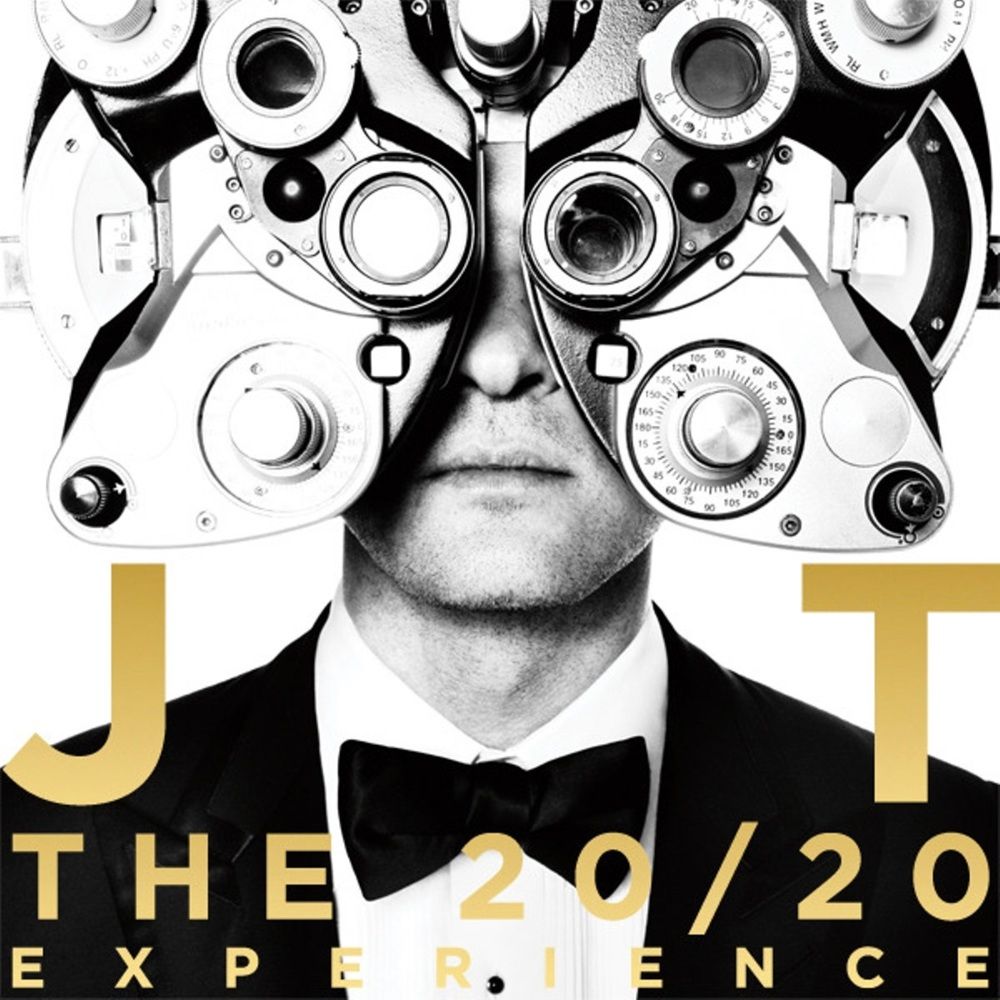

Justin Timberlake returned in 2013 with The 20/20 Experience, a largely satisfying collection of Timbaland-produced serpentine pop music that recalled the creative partnership’s FutureSex/LoveSounds glory days; later in the year, he hubristically released a second and largely inferior volume that was riddled with controversy and awful country songs.

The 20/20 Experience - 2 of 2 less signified Timberlake’s true artistic decline as it did the hazards that come with attempting to extend a promotional lifecycle with whatever’s left over in the studio; since then, the streaming economy and a shorter-term attention span from the general public has resulted in an absorption of that lesson in the form of the increasingly prevalent “deluxe editions” released weeks, months, and even years after popular albums are initially released. The still-emergent method of stream-juking sidesteps the pitfalls that Timberlake’s album fell victim to, offering just enough fresh content to reinvigorate interest in the artist and the project itself without offering too much for the re-release to be unfavorably judged on its own.

Timberlake wasn’t the only pop artist to barely escape 2013 with fresh wounds. After several years of highly successful myth-making, the Weeknd’s Abel Tesfaye dropped the curtain in front of his once-shadowy image with his proper debut Kiss Land. If the releases collected on Trilogy the previous year represented a new and highly influential strain of R&B that infected pop and indie spheres, then Kiss Land found Tesfaye and his collaborators pushing that aesthetic fully into the red to nearly deleterious effect.

(Nothing quite recalls the vapid excesses of both the music press and the music industry itself than the Kiss Land listening session I attended with several Pitchfork coworkers, in which we were forced to listen to the album at deafening volume in a karaoke room tucked away in NYC’s Koreatown area, with obscured footage of softcore pornography nauseatingly complimented by trays of over-fried karaoke grub and syrupy cocktails. Just another example of an experience that, for better and worse, won’t be returning any time soon.)

Kiss Land was a dire album that seemingly turned Tesfaye’s career fortunes overnight from “promising” to “once-promising,” and even though the album was a commercial success regardless (I don’t think it can be overestimated just how big of a star he was upon first impact), he clearly took note of its failings. Over the rest of the decade, Tesfaye re-styled himself from his former status as an ex-American Apparel staffer who loved sampling Beach House to a canny pop superstar flirting with “cool” sounds while still aping the tried-and-tested stylings of past iconoclasts like Michael Jackson.

Arguably, Tesfaye wouldn’t have the still-wildly-successful career he currently has—not to mention his increasingly-getting-better catalog of pop music—without the miscalculations of Kiss Land providing instructive in where he needed to take his music next. And his mostly-abandonment of the murky and miserable R&B that Tesfaye established also left the lanes wide open for the legions of imitators that still pile on to this day.

There’s a lot more to touch on here—specifically, Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines,” Miley Cyrus’ Bangerz, Sky Ferreira’s Night Time, My Time, Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories, Kanye West’s Yeezus, and Beyoncé’s Beyoncé—that would cause this essay to double in length. Hence the “Pt. 1” in the headline: next Tuesday, I’ll publish the second and final part to this essay, along with an essential 2013 playlist covering everything mentioned here and a little more, too, so stay tuned.