44 Thoughts on FKA Twigs, Phoebe Bridgers, Drinking, Beyoncé, Nick Jonas, and the New Pop Chaos

This is a free post; paid subscribers also receive a weekly Baker's Dozen playlist featuring music that I've been listening to lately, along with some critical thoughts around that music. As long as I can afford to, I'm donating all newsletter revenue to the National Network of Abortion Funds. So far, $2,317.64 has been donated.

- A few weeks ago, someone (I believe it was loyal newsletter subscriber @itsmattfred, but I could be mistaken) replied to me on Twitter that Beyoncé's astounding new album Renaissance could be, to them, the defining "pandemic-era album." And that of course got me thinking about that concept, as well as what the best album of this decade so far could be.

- Let's focus on the second thing for a moment, just for fun and to clear it out of the way (hey, these transitions aren't going to transition themselves). If we're talking about how critical apparatuses operate, Fiona Apple's Fetch the Bolt Cutters seems like a shoe-in for any mid-decade hosannas right now, no further guesswork required.

- It hasn't been a knockout decade for undeniably classic albums so far, if we're being honest—but that doesn't mean the bench is totally empty. Jazmine Sullivan returned last year with the typically virtuosic Heaux Tales, Waxahatchee's Saint Cloud perfectly captured the searing clarity that comes with embracing sobriety, Jane Remover's (fka dltzk) Frailty stands as a gorgeous and complex high water mark of craftsmanship and songwriting in the ever-changing hyperpop/digicore/insert-other-subgenres-here scene(s). Some will rank Taylor Swift's overtly trad gestures Folklore and Evermore highly as the decade trudges on, perhaps forgetting that her more strident work (especially 2019's Lover, which stands as quite possibly her most thrilling and fascinating album to date) was far more interesting than the Dessner-assisted drudgery she's recently committed herself to.

- Beyoncé's Renaissance is a strong, if not the strongest, contender right now, and we'll talk more about that album in a few. Prior to its release, my answer to the question of "What's the best album of the decade so far?" would've arrived from my lips, typing fingers, whatever easily and without reservation: Phoebe Bridgers' Punisher.

- Similar to its closest spiritual kin, Feist's utterly classic and era-defining The Reminder from 2007, Punisher felt meteoric upon immediate arrival, and sometimes it feels like the last two years have been collectively spent staring into the crater its impact made in the ground. It elevated Phoebe Bridgers from rising star to superstar practically overnight, and the imitators of its easily-copied, never-perfectly-imitated sound have already begun coming out of the woodwork (and if you're a paid subscriber—plug—you'll get an idea of who some of those imitators are in the months/years to come).

- Punisher uses sadness the same way I imagine painters use primary colors (I don't know anything about that type of art, so sue me), creating subtle new textures from song to song while radiating an unmistakably melancholic glow throughout. Even its most presumably uplifting moments—the oceanic chorus of "Kyoto," the intimate sweetness of "Graceland Too," "I Know the End"'s jet-engine finale—possess a deeply felt darkness just underneath, as if we're witnessing their true nature through a glass-bottom boat. Punisher is pain and passion intertwined like a DNA strand; I have the entire album committed to memory at this point, which is fortunate since I may never be able to actually listen to it again.

- When I was drinking, I had a strange but undeniable affinity for hangovers. Nothing sounded as good as music did the morning after tying off a few with friends, or with myself. That intense vulnerability and defenselessness that courses through your body like a fever—the literal aftereffects of poisoning yourself, seratonin fully depleted as your overall sensitivity is dialed up to level 1,000—I was as addicted to it as I was to drinking itself. It felt like my superpower, a way of unlocking some deeper understanding about how music feels; I'd form deep relationships with music in this context, with a mental Rolodex of sounds and songs that would absolutely devastate me in the afterglow of sickness.

- When I quit drinking, there were a lot of fears looming in the distance—even as I lived within the pink cloud of intense gratitude that, after a year and a half of searing depression and self-medication that had accelerated my alcoholism from "I can manage it, haha" to "What is this void I'm staring into, and why won't it stare back?", I had managed to unlatch myself from the tit of dependency. Would my friends accept me? Could I "hang" the way I used to? What would I do with all this free time? Was I resigned to a life of regret, all past enjoyable experiences of intoxication cast in the new light of relative sobriety? Would it be possible for me to unlock—to understand—the deep emotional blues and purples of popular music without my aforementioned superpower at my disposal?

- Before I go any further, let's do a brief air-clearing: For me, these concerns were largely unfounded. Nearly a year and a half after I quit, my life is very much better and more worth living than when I was in deep with the drink. Occasionally—and, luckily, a lot less often than I'd expected when quitting—I'll be in a situation where friends will be enjoying themselves with drinks around me, and I'll think to myself with a little bit of sad distance, "I used to be a part of that."

- Then I remember what being a part of that meant in terms of how I felt about myself, and the illusion fades. I'm brought back to reality, which is not always the most fun place to live, but there's really no better substitute for it, either, and reaching the end of another day in which I don't "pick up," as they say, is as rewarding and fulfilling as witnessing another morning sun.

- I'm a bit of a practicing agnostic when it comes to "the rooms," which are extremely helpful for many but more of a "they're there when I need them and that's comforting enough for me" presence when it comes to my own personal recovery. I do find a lot of value talking about my alcoholism publicly and without shame, I like talking in general (can you tell?), and I'm always happy to talk to others struggling with alcoholism if they need a sympathetic ear. If you need it, my email is larry.fitzmaurice@gmail.com; I don't always reply with expediency, but I promise that I will always reply eventually.

- When I was drinking—specifically, when I was drinking from June 2020 to when I quit in April 2021—listening to Punisher was a secondary vice. I'd never listen to it in the literal throes of drunkenness, as I had other albums that were effective in that regard; Sufjan Stevens' The Avalanche for my anger and depression, Titus Andronicus' The Monitor for recreating some sort of rollicking house party in my head, Queens of the Stone Age's Songs for the Deaf for indulging pure dusky decadence. It helped ("helped") that all three of these albums were long. What's eight more drinks when there's eight more songs?

- Punisher was for the mornings and afternoons and early evenings after, the perpetual scratched itch for feeling smaller than the world around me as that world also seemed, like me, in some sort of state of perpetual decay. Listening to it in this context was like tonguing a cut on the roof of your mouth, or picking a scab (which, perhaps coincidentally, I just found myself doing while writing this paragraph); it was pleasurable pain, something I couldn't stop myself from doing even if I wanted to do, which I didn't. I was under no illusion that my feelings and those weaved into Punisher's framework in any way lined up, there were none of the parasocial "She's just like me, maybe" delusions that come with so many people's listening habits these days. Punisher just sounded like pain to me, and I was in pain, and just like popcorn and a soda at the Regal theater chain, Punisher and I were perfect co-stars.

- I've listened to Punisher precisely once since I quit drinking—specifically, during last year's holiday season, when new life complications were emerging and I felt like gravitating towards something that allowed me to lay in a metaphorical ditch for a spell. I found the experience to be vulgar in its self-indulgence; the music sounded perfect, as I still believe it to be, but otherwise I had a reaction that must be similar to when people quit cigarettes through hypnosis and a Camel between their lips feels like a snake, or a piece of dog shit. I didn't need it, I don't need it, and I don't want it. I'm not sure I ever will again, and I feel no sense of mourning about this theoretical loss. Life goes on, and there's always more new music just around the corner anyway.

- Punisher isn't a "pandemic album" by design, but it feels incidentally pandemic-esque. I have no doubt that Phoebe Bridgers would've become a superstar off of it regardless, but I am also under no illusion that I am the only person who heard Punisher in 2020 and thought, "This sounds sad, just like me." There were "pandemic albums" released in 2020, and given the massive delays in release schedules that the pandemic itself wreaked, there will continue to be "pandemic albums" for at least another year or so I reckon. If I had a dollar for every piece of bio work in which the client's told me their album was influenced by the pandemic, before quickly adding that they would rather reject the "COVID album" narrative...I'd have quite a few dollars.

- When it comes to indie artists—and I'm using that term to designate artists and bands of any size below explicit major-label-signed acts, so just bear with me—I don't have much interest in picking out the specific inherent flaws of said bodies of work. I hear records "like that" and I hear other people struggling to work their shit out at a time in which everyone was struggling to work their shit out. It makes me feel anti-critical, or at the very least, it makes me feel like criticism has its time and place when it comes to assessing others' artistic expression. Sometimes you just need to get the stuff out of you to move on, and hey, honestly, if it works for the person getting it out of them then I am in no place to judge what form that takes.

- That being said! During a specific period of time—let's say summer/fall of 2020 to winter 2021—when big-ticket pop music attempted to address the pain and isolation that accompanied so much daily life around that time, it more often than not felt disgusting to me and totally unrelatable. When I hear something like BTS' "Fly to My Room," which attempts to address the driftlessness and endlessness of the quarantine age, I hear people who could not possibly understand what the vast majority of the listening public was actually going through at the time.

- The only exception that comes to mind is Charli XCX's How I'm Feeling Now, which probably came closest to connecting with people "on the ground" when it came to the mental gymnastics so many were doing during the first months of COVID. Of course, meeting people where they are is kind of Charli's whole thing, both a feature and a bug of her relative size in the pop stratosphere—which made her especially equipped for responding to that specific moment in a way that didn't feel totally gauche and tone-deaf.

- When I think of Public Enemy No. 1 in terms of pop stars' foolhardy attempts to evoke what it's been like to live through COVID, I think of Nick Jonas. His 2021 album Spaceman was heavily influenced by the pandemic, assumedly written and recorded when he wasn't watching Priyanka Chopra clap for essential workers like a goddamn weirdo from whatever massive house the two of them reside in.

- "What’s the one thing that all of us have felt during this time?" Jonas told Zane Lowe before the album was released. "Completely disconnected from the world. We’ve gotten so accustomed to looking at a screen instead of human interaction, and I think the thing that keeps us all encouraged and hopeful is the idea of knowing that there will be a tomorrow when this is our reality.” If you read that quote without immediately thinking "Go fuck yourself," you're stronger than I.

- Spaceman has the fingerprints of pop guy Greg Kurstin all over it, which is to say that it's moderately tuneful and could've been made by any white person over the last seven years. It would've left little impression on me were it not for "2Drunk," a vibey trifle in which the lyrical preoccupations are self-evident. "And, oh, I think I just hit my stride/ 'Til I wake up and hate my life/ I'm too drunk and I'm all in my feelings," he sings, and even as my most cynical sense of being triggers a response of "You're rich! You can throw money at pain! The rest of us simply cannot!," the alcoholic in me also thinks that, yes, sometimes it really do be like that.

- The first time I heard "2Drunk," which I also featured on a past Baker's Dozen (yes, another subscription plug, deal with it), I felt uneasy and sideways, like I had landed on the ground after someone had gently kicked me in the head. The sentiments felt uncomfortably familiar, taking me back to a place I knew but did not care to continue knowing. "Gee, I really don't like this feeling," I said to myself while slotting it into one of my many in-progress Baker's Dozen playlists. "I hope I don't feel like this again any time soon."

- In mid-December 2021—probably a week after I suffered through House of Gucci in theaters—I walked my wife to the subway in the morning before doubling back to our apartment. As I approached our block, I saw a massive line stretching around the distant corner and coming right up to our front doorstep. I didn't really need to confirm its point of origin, but I did so anyway and found a COVID-19 testing site at the head. Omicron was raging, and this was the result.

- I felt disoriented and sick and panicked almost immediately. Living through the first year of COVID in NYC was absolutely horrible with few exceptions; at its worst, you felt surrounded by death and overflowing with grief, and the conversations I've had with many others who did not live in NYC during those first few months have confirmed that this was a specifically local feeling mercifully unreplicated in their own lives.

- Before COVID hit, I was already living in a pit of depression that I was dealing with through drinking. When the pandemic exploded, I unlocked new levels of sadness and substance abuse that commingled with each other like aerosols finding hosts in an unventilated room. The fact that I was able to pull myself out of such an absolute personal morass—somewhat symbolically, the day before I received the first dose of the vaccine—felt like the best thing that happened in my life after meeting my wife in 2008.

- When I saw that snaking line on my block, I had a reaction that I suppose could be described as PTSD, even as I'm hesitant to self-diagnose in the age of "You can't actually get mad at me for working at Goldman Sachs, because I have ADHD." I ran upstairs to our apartment and threw myself on the bed and started crying because I was so scared of being taken back in any way to that first year, when sickness was in abundance and I could feel nothing but deeply and spiritually unwell. I didn't want to go back, I really didn't want to go back, I cannot emphasize how much I did not want to go back.

- It's worth mentioning that despite the familiar feelings, I had no urge to drink again, and have had no such "close calls" or strong desires since putting the bottle down. It doesn't work like that for me, at least not yet, and I consider myself extremely lucky in that regard because I know my compatriots in suffering and surviving struggle in different ways as well.

- But things felt freshly weird and bad again, even as I considered myself not one to be lulled into the false sense of security and privilege that being white and vaccinated during the pandemic has provided so many fellow white, vaccinated pandemic endurers in the U.S. and the world over. It was a reminder that, yes, I might have left booze behind, but maybe I'll always be a little bit (maybe more than a little bit) fucked up from this mass collective experience of death and devastation. Shit will simply never be the same, and what's worse is that acceptance of that truism doesn't make any of it easier to deal with.

- Over the last several years leading up to 2022, much of what major-visibility pop music has had to offer has been insular and murky. This is a phenomenon—an anti-phenomenon, perhaps—that kicked itself off around 2017, when what I've previously defined as the "new emotionalism" generally told hold in pop music at large. Big Statements from Big Pop Stars have generally been few and far between, as many of those Big Pop Stars have mostly stayed out of public view and/or focused on lining their coffers through other non-musical means.

- So much of what's left has taken a similar timbre of purple miserabilia, awash in glowy synths and varying levels of lyrical toxicity. More than a few of the artists who inspired this approach—I'm thinking of the likes of Lil Peep, XXXTentacion, and Juice WRLD—are dead now, their imitators hammering imitations into the ground with increasingly diminishing returns.

- As I chronicled for the New York Times earlier this year, some of pop's biggest female-identifying stars have clearly taken note of their perishing peers and the harmfulness of fame that contributed to hastening those peers' demises, and through their own work they've expressed a desire to walk away from it all. Bottom line: Pop music from 2017-2021, not really a very happy place.

- The album as a format has possessed a similar fickleness as far as its presence in pop music around this time. More often than not, big pop albums have taken on the shape of a collection of songs instead of a true statement of purpose, even when there are purposeful statements being made within the music itself (I'm thinking about Happier Than Ever, Solar Power, and I think Sour does fall under this umbrella as well).

- But something has changed in 2022, as we're suddenly awash in big, bold pop albums engaging in both stylistic playfulness and structural integrity—music that feels and sounds 3-D, its sequencing more integral to experiencing it than in previous years, teeming with an organized chaos that mirrors the experience of living itself. Of all people, the Weeknd—who's been plenty guilty in the past of overdoing that purple miserabilia I was talking about before, and might actually be a pre-Peep locus point for its origins—kicked everything off with the flashy and celestial Dawn FM, which filtered producer and Oneohtrix Point Never mastermind Daniel Lopatin's radio-obsessed preoccupations into the kind of lush, glowing R&B that Abel Tesfaye had previously flirted with but never quite embraced on a full tilt.

- Four years after her striking breakthrough El Mal Querer, Rosalía returned as M.I.A.'s sonic heir apparent with the spiky and thrilling MOTOMAMI, an album of serrated edges and sticky mantras that never seems content to sit in one place, psychedelically changing its own structure while retaining an unmistakable overarching form. Bad Bunny's Un Verano Sin Ti was another huge album-length banger from him as well as his greatest statement yet to date, delightfully throwing myriad sonic styles over his shoulder like a greedy hypebeast in search of the perfect fit as a colorful pile amasses behind him, just waiting to be dug through again and again.

- Beyoncé's Renaissance is obviously a stunning and virtuosic example of this phenomenon as well, the latest and greatest example of pop music getting a little left-of-center and being very generous with its own exploratory perspective. An epochal album that further confirms Beyoncé's place in the realm of pop music history alongside vanguards like Prince and David Bowie, Renaissance is so brain-blowingly good that it still feels hard to talk about beyond pointing in its direction and saying, "Can you even believe how good this record actually is?" After wearing it out nonstop upon release, I took a week off from listening to it, and then I went back to Renaissance on repeat as soon as I first heard it again. I can't think of another big-deal pop record in years—the last A Tribe Called Quest record, maybe—that I've had that experience with.

- As a work, Renaissance is a devotional to some of society's most historically marginalized groups; its focus is largely empowerment and uplift, finding solace and ecstasy amongst the pain that daily life so often doles out in no small amount. It's extremely powerful stuff, and perhaps its power is not explicitly designed to be absorbed by, say, a 35-year-old cishet white man—but, regardless, I find it to be totally and emotionally overwhelming, especially on moments like when she sings "I've been up, I've been down/ Feel like I move mountains/ Got friends that cried fountains" over the body-moving juke-flecked gospel of "Church Girl."

- "The rest of the world is strange," she flutters over the rustling neo-soul of "Plastic Off the Sofa," "Stay in our lane/ Just you and me/ And our family." We know who she's singing to, of course (what is a Beyoncé record if not a document of reaffirming one's commitment to monogamy?), but the we-are-still-here-at-the-very-least sentiment is affecting, welcoming, and comforting, the type of thing that anyone struggling with anything can potentially find solace in.

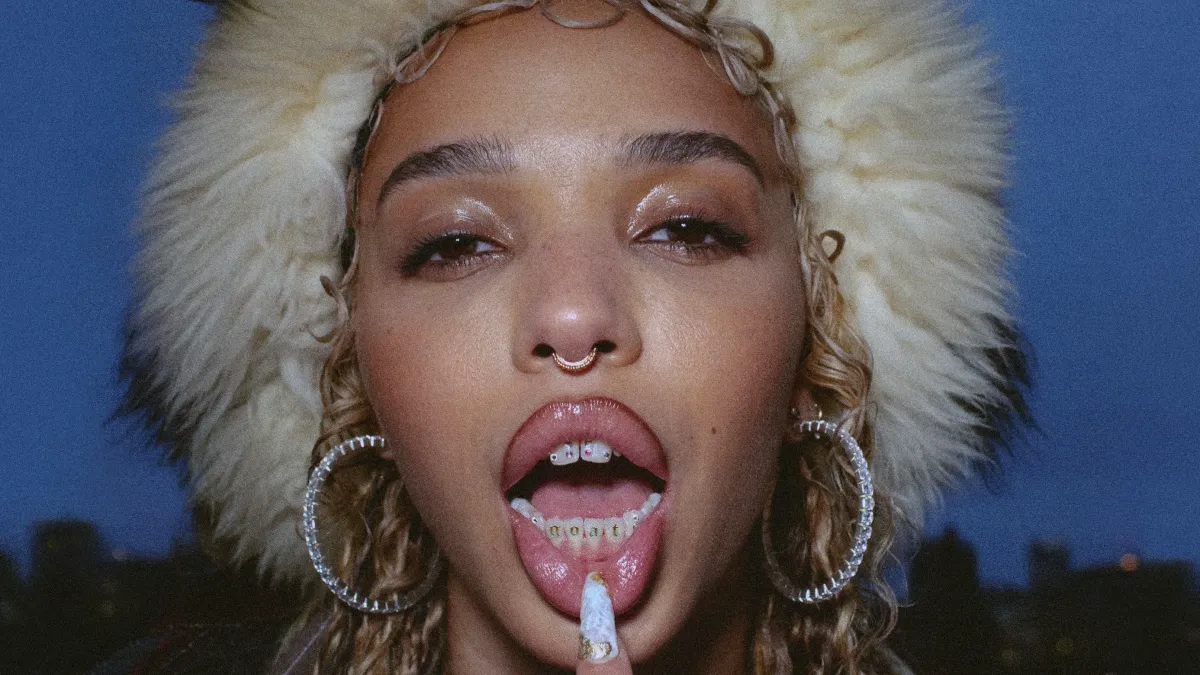

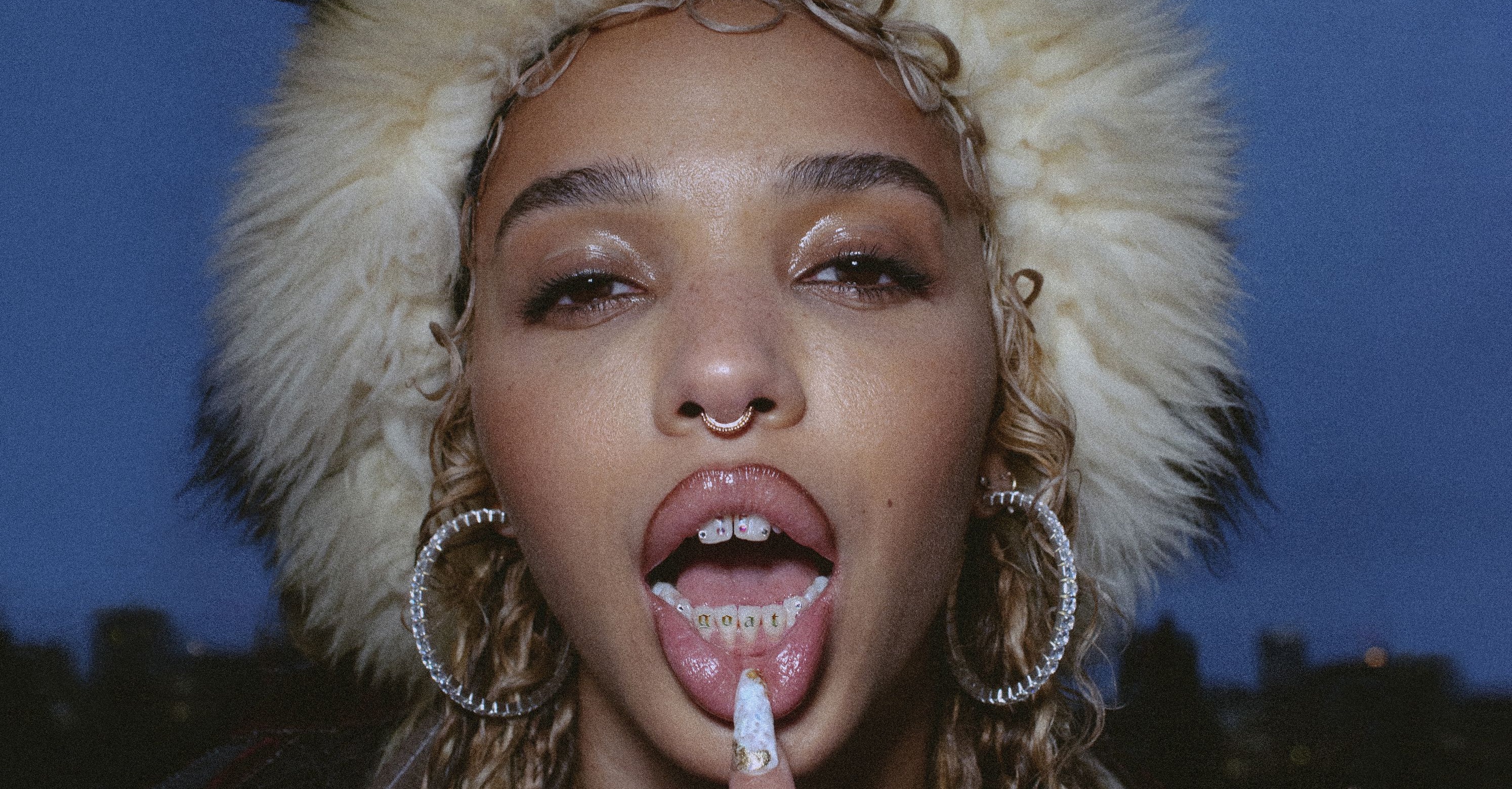

- Thus far (it's only been out for a month, after all) the sentiment I most closely associate with Renaissance is "Don't worry, it's okay," which I also found myself ascertaining from FKA Twigs' astounding and weirdly underrated Caprisongs from earlier this year. The record was billed as a "mixtape" and certainly plays like a considered replica of the sort; it literally opens with Twigs saying, "Here, I made you a mixtape." The act of giving is stated up front, a sense of generosity directly communicated to the listener. I made this, and it is for you.

- Before Caprisongs, I ran hot and cold on FKA Twigs. The early stuff (I'm talking the first few EPs) was fire, "Kicks" and "Two Weeks" are very impressive songs specifically, but otherwise LP1 and Magdalene left little impression, the weightiness of the work oftentimes overpowering what songwriting there seemed to be. I've occasionally returned to LP1 to marvel in its slippery, slow-motion distortion Tetris Effect-esque production, and I've had zero desire to return to Magdalene since it was released.

- I understand I'm kind of in the minority there, and that the general "pretty good" critical reaction to Caprisongs was largely due to the absence of such searing, personal excoriation that critics have come to appreciate and possibly prefer from her. Or, put quite simply, in today's critical landscape music more often than not has to sound like it weighs a million pounds to receive serious adulation, which is a topic possibly (or possibly not) for another time.

- Caprisongs is not without its moments of sadness; there's a song called "Tears in the Club" that transmutes melancholia into its own kind of ecstasy, and amidst the rubbery rhythms and air-raid sirens that pepper the album there's also downtempo moments of contemplation. But it's all executed with an unusually light touch, as if FKA Twigs is simply skipping stones across the stillness of a pond's surface. The overall experience evokes the joy of life's chaotic structure, the ability to find solace in celestial randomness—the generational tendency to, as I've quoted Kacey Musgraves before and will likely do so again in the future, feel "Happy and sad at the same time."

- Caprisongs arrived roughly a month after I had my COVID-era PTSD moment, when the testing lines were getting shorter but there was still this disorienting effect of everyone getting sick again, time slowing down again, all the "again"s piling up in my head until the deja vu became too much to process. In the beginning of the pandemic, interacting with so much pop music meant coming away with the feeling that you were, in fact, alone in this—that the stuff you consume, the people who make it, do not care or understand one whit about what life is really like in that moment.

- Maybe it was naivete on my end, maybe it was spiritual exhaustion, but I felt something different from Caprisongs on first impact—that it was a record made in the same open-hearted vein as Renaissance, something that extended its arms out and said, "I know, we're all dealing with this too, it's okay." Perhaps this feeling I ascertained is just another permutation of the parasitic attachment I developed with Punisher a year and a half previous; maybe that's the curse of being someone who cares about pop music and believes in the potential for a single sound to change your life, even if it's only for a few minutes.

- But then there's that snatch of sampled dialogue that opens up the gorgeously tumbling "which way": "This is, like, the perfect music to think...It's like elevator music, but you're going to the fiftieth floor. Mmm, made me realize I have no thoughts though." Sometimes, that's okay too.