Kip Berman on His New Album as the Natvral, The Pains of Being Pure at Heart, Parenting, and New York City

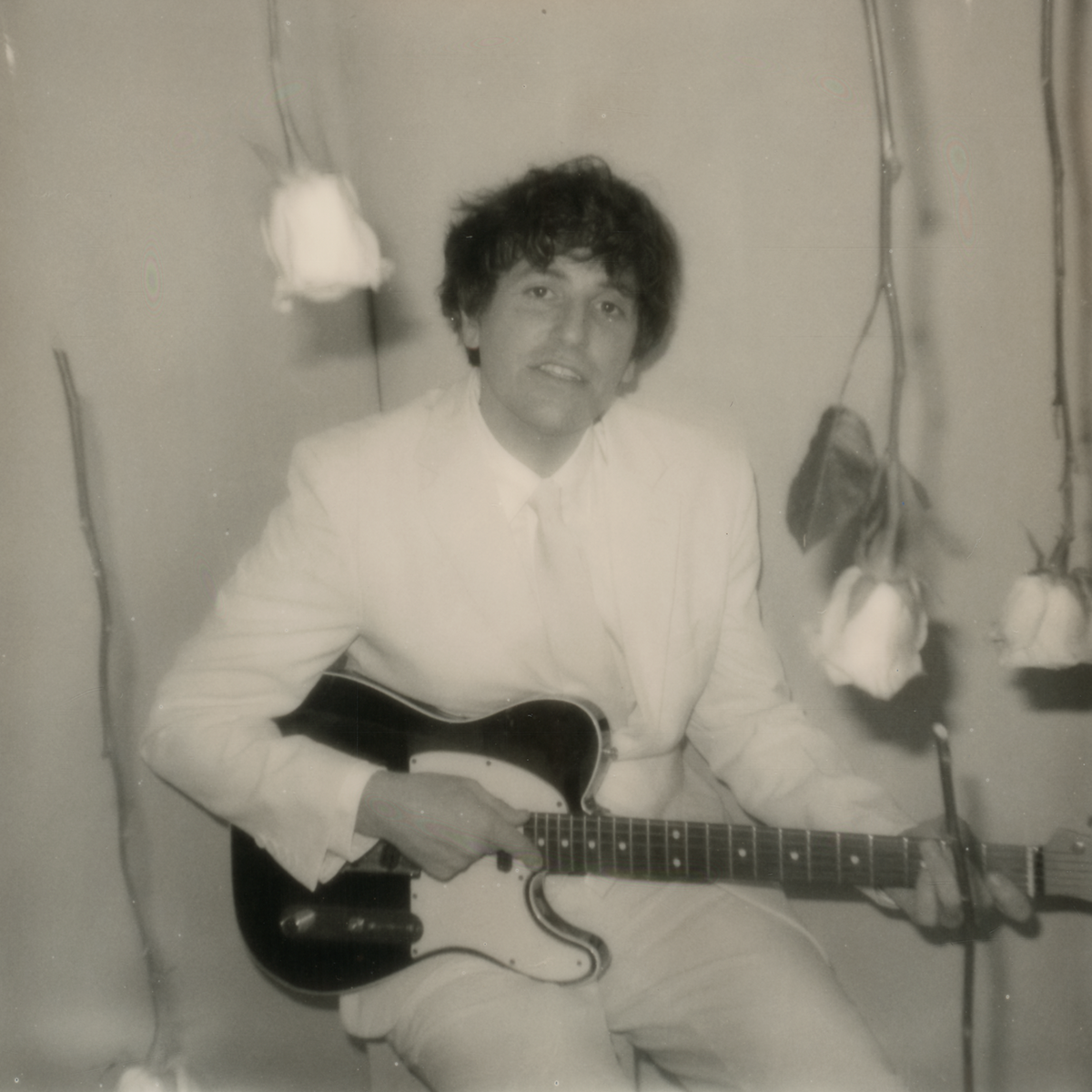

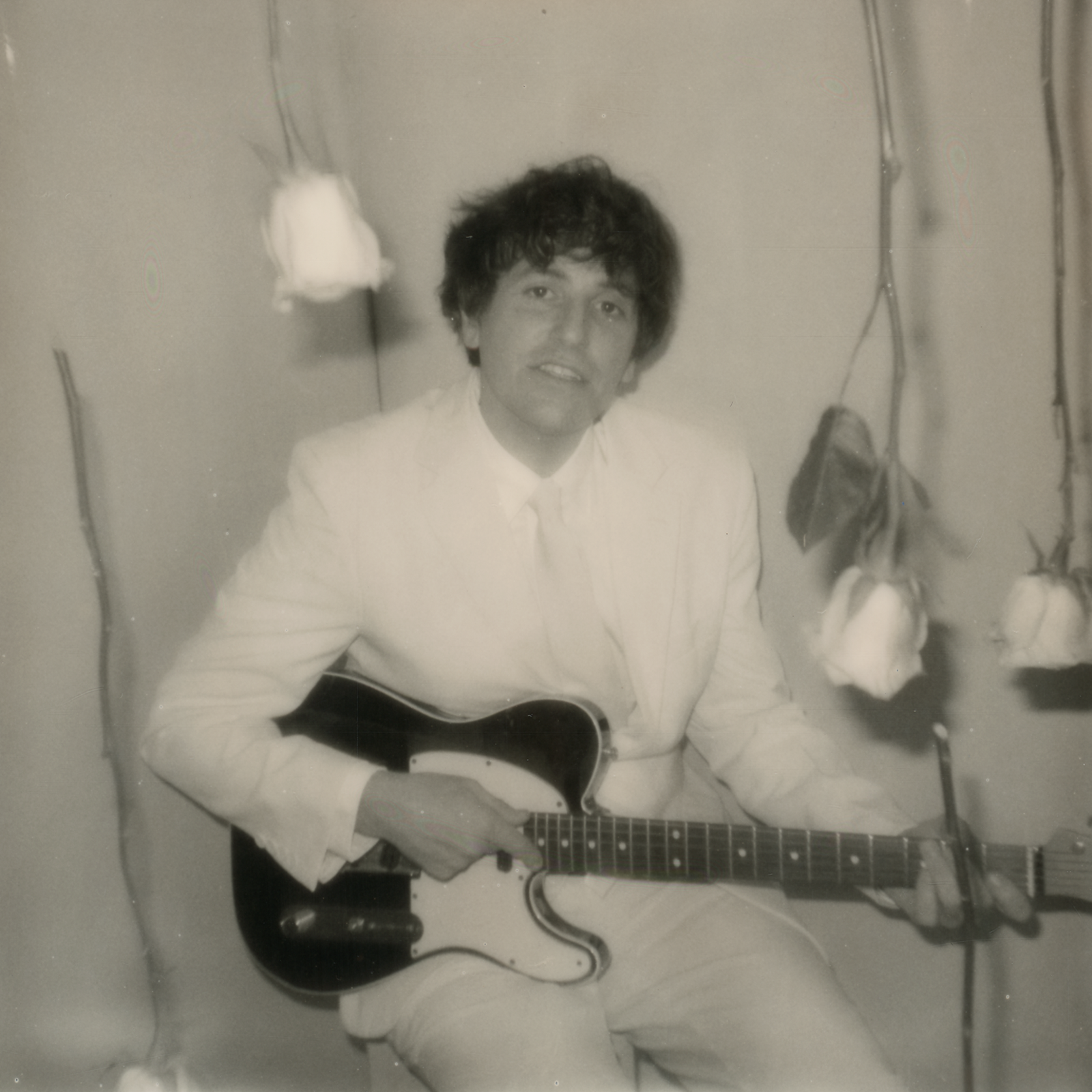

Kip Berman by Remy Holwick

Kip Berman—formerly of The Pains of Being Pure at Heart—has a new album out April 2 as The Navtral, and it’s a fascinating switch-up from the sound that you might have come to expect from him. Instead of mining Slumberland-era indie-pop, this new music takes more of a ramshackle singer-songwriter approach, feeling very loose and off-the-cuff while retaining the same melodic sensibilities he exuded in Pains. We had a very fun and loose conversation too.

Tell me what you’ve been up to over the last six years.

We recorded the last Pains record in January 2016, and my wife was six or seven months pregnant too, so we were trying to get the record done before the baby came. In April of that year, my daughter was born, which was really cool and shifted everything in my life. We moved to Princeton shortly thereafter, and I was staying at home with my daughter all the time, walking around with her in the stroller and spilling coffee on myself.

The Pains record finally came out in 2017—I delayed the release because I couldn’t tour or anything. We did a little bit of touring, but not as much as we’d done in the past, because I didn’t want to be away from home that long. Before my daughter was born, I was worried about being a dad and having to travel while making music. But after she was born, I didn’t want to travel. I just wanted to be home.

After finishing the last Pains album, whatever energy I had was gone. It wasn’t writers’ block, I just had no desire to create in the way I’d done with Pains. It had gone away, but peacefully—it wasn’t a struggle, it just felt removed from my interests. I’d just play music on my own. A lot of the time, it was just funny songs for my daughter to pass the time. The kind of music I was listening to was really different, too.

My mom came over and listened to what I was doing one day, and she was like, “This reminds me a lot of Richard Thompson.” He plays one concert in Princeton every year, it’s the only concert that happens here. Then I went back and listened to those Fairport Convention records. I must’ve had the wrong idea of what Fairport Convention was, because I thought it was some hippie thing, but it was really cool. It was one of those things where you dismiss it and never listen to it, and then you listen to it and you’re like, “I was so wrong.”

Bob Dylan, too. It’s not like I’d never listened to him before, but his gatekeepers are the worst advertisers for his music. There’s this mythology that prevents you from approaching him. It does a disservice to the spontaneity and playfulness of his music. Once I went back to that music, it was like hearing it again for the first time. It was really inspiring to me.

With Pains, there was always a sense of striving for an ideal beyond ourselves—I always called it “Heroic amateurism.” There’s something good about that, when an artist tries to do something but it comes out another way. But this music is so different. There was no metronome, no overdubs. These are the songs that me and my friends put together after pressing “record.”

Being a dad, I can’t just book four weeks in the studio. I have one day to bash out as much as I can. So it was done fast and loose, but it’s not like I had another choice. It was the only way to do it.

How has parenting been in the pandemic for you?

It’s interesting. The record was done before the pandemic started, so in that respect I was lucky. I don’t know how to phrase it the right way—it’s like writing an email these days, where you want to let people know that you’re doing okay, but you also don’t want to sugarcoat the reality that a lot of people aren’t. Both children were with me, the schools were closed, but they’re both really young, too. They closed all the playgrounds, so I became the jungle gym. My daughter calls me “Daddy Jungle Gym.” Trying to spend an entire day with two children without being able to do the things you do with two children…we were just inside, trying to get through it.

I was relieved when the preschool opened again last fall, to resume a sense of normalcy. But a lot of the hardship was on my partner, who worked from home. So the expectation that she has to work full-time while at home means there’s no delineation between when she’s on work and when she isn’t, and when the kids see her they want her to make time for her. And she does, in a great way, but the demands of her life are much harder than for someone whose existence is much more flexible. It’s not like we’re not going to be able to eat because I can’t play guitar in the basement for a while. [Laughs] I don’t want any sympathy for my situation, because it’s not as bad as what other people are facing right now.

As someone from the Northeast who had their first career breakthrough in New York City, what do you think the allure of the city is for people who are into music?

Well, everyone I’ve ever met from New York City is either from Florida or Ridgewood, New Jersey.

I’m from Ridgewood, too.

Really? [Laughs] There’s so many bands from that North Jersey enclave. Titus Andronicus, Real Estate, Big Troubles, Vivian Girls…

I grew up with all of the people in those bands.

Amazing. Even Alex from Pains is from Teaneck. I went to school at Reed outside of Portland, Oregon, so coming up from where I was in Pennsylvania to Portland—which is I guess what you’d call a super-progressive, bohemian DIY community in all these cool ways—because I couldn’t go to bars yet, I’d be in basements and trying to book bands in ping-pong rooms. Dear Nora was my favorite band. Magic Marker Records would put on shows at this house, and Jonah from YACHT and Katie from Dear Nora lived there. I’d always walk up there and go. Touring bands would play there, too—I saw Mates of States there, and the Lucksmiths—and I’d try to book them at the school for, like, $50. [Laughs] The Gossip would play benefit concerts all the time too.

The Pacific Northwest is so geographically situated away from everything else that a lot of those bands didn’t get a chance to tour beyond the area. San Francisco was a 12-hour drive, and so was Boise. It was a community of bands that existed in that region, and it felt very regional because of that. Bands could be big, but only big there. So the allure of New York, where I was working at a call center where I’d be recharging people’s prepaid cell phones at 3 a.m., and I was around other people who not just shared the stuff I was into, but turned me onto other things.

The dream of New York is being around people that are both like you and not like you. That’s the eternal appeal. I love New York City, but I also love Princeton. There’s a great record shop, there’s parks where my kids can play, and I don’t have to carry a stroller up six flights of stairs, which is nice.

I seem to remember you guys being on MTV around the first Pains album. Am I just making that up?

We did some stuff for MTV U around the second album. When the first album came out, ABC News showed up at my friend’s basement and wanted to talk to us and watch us play a song in the basement, which seemed crazy.

A lot of people would be like, “You’re from New York, you must hang out with Vivian Girls and the Drums all the time.” But we never got to know any of those artists until we were kind of thrust together by an external perspective. We shared a practice space with Crystal Stilts, who I loved. If you went to the coolest party in New York, they’d be the ideal band to see there—like seeing the Velvet Underground.

Vivian Girls were so cool, they were really doing it. They were so kind. We were supposed to play the UK once but the band we were opening for dropped out, and they were like, “You can come play on our shows.” They were really generous. It was hilarious—we were playing a show in London, and all these British kids are dressed like they’re in Bushwick and chanting “Brooklyn! Brooklyn!” at the stage. I was so flattered that Vivian Girls thought we were cool, because I was like, “We’re just nerds.”