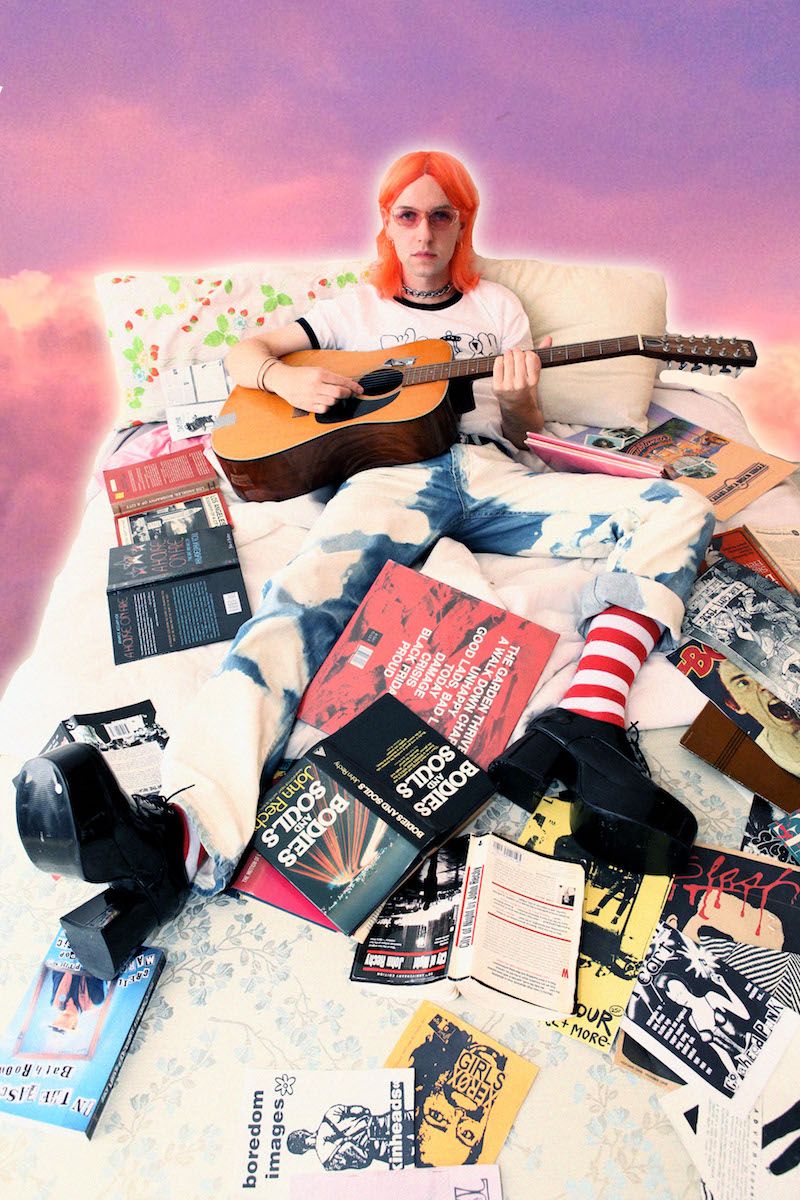

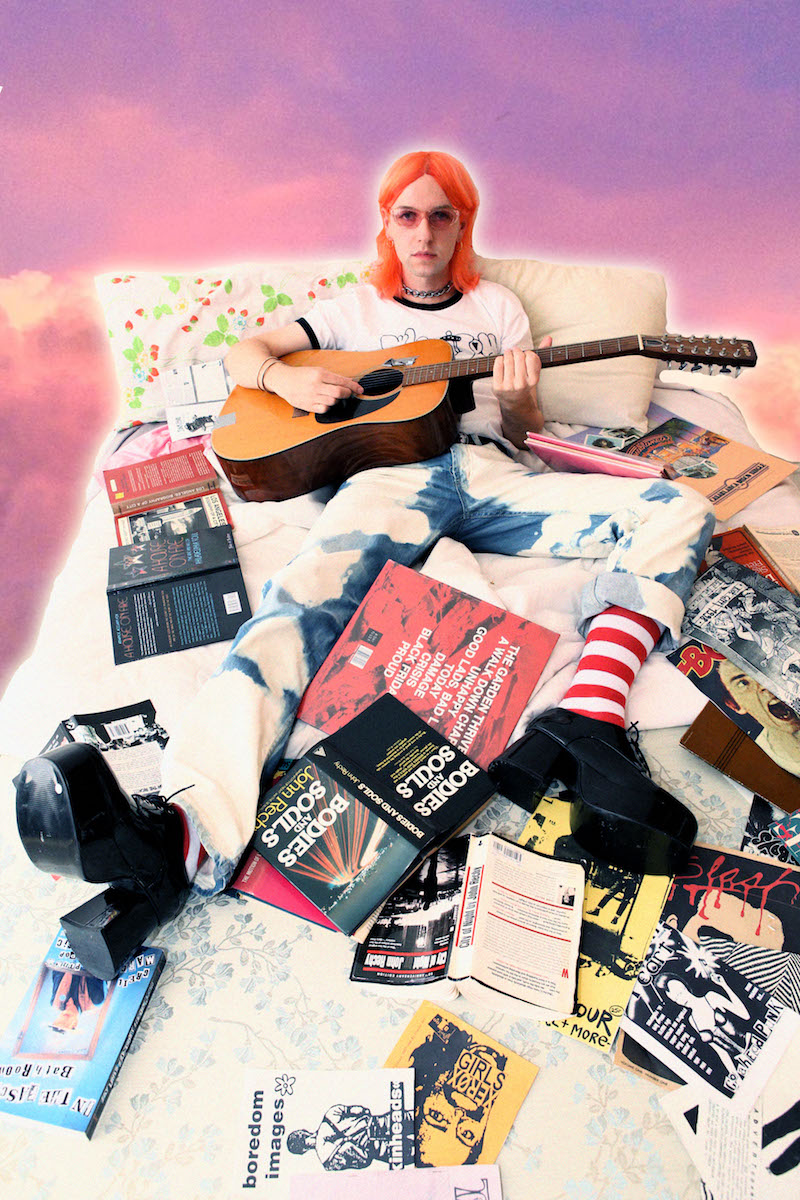

Jam City on His Fantastic New Album Pillowland

This Tweet in the Queens of the Stone Age micro-discourse on Twitter from a few weeks ago stuck with me:

I always remember Josh saying in an interview a band’s first record should be a solid statement of what they are, the second should stretch that out and experiment with everything, and the third should combine the best of both. I’d say they did just that.December 3, 2020

I think that describes Jam City’s discography to a T. Jack Latham’s first album, Classical Curves, was a jagged and alluring collection of abstracted dance music that he and UK label Night Slugs had built their name on, while 2015’s Dream A Garden found Latham diving headlong into smeared-lens New Pop and new-wave. His third album, the brilliant and bold Pillowland, combines the two approaches with aggressive synth patterns and blown-out glam rock hooks. It’s one of the most fascinating creative about-faces of the year, and I hopped on the phone with Latham earlier this week to talk about a variety of things.

What has this year been like for you?

It’s been weird, man. It’s been tough for everyone in different ways. If I’m completely honest, it hasn’t been that bad for me work-wise. With the record, I was definitely planning a tour, but nothing was organized before March, so I didn’t have any cancelled shows. To be honest, a lot of the work I do at the moment is production for other people, and that more or less continued to pay. But the feeling of real life being paused is just super hard.

It’s been five years since your last Jam City album. Walk me through what went on during that time.

I’m writing music all the time, whether with myself or other people, but this one didn’t come together until the end of last year. I didn’t know what it was, and then things started to solidify. When we started working on the artwork, things started to come together in a nice way. There was a lot of travel, and I lived in Los Angeles for a little over the year for work, so living in the States definitely influenced the record. It definitely doesn’t sound like a UK record [Laughs]. It’s preoccupied with that time living in California after having been obsessed with American culture since I was born. The dream came true, but it wasn’t as quite as it seemed.

Moving around meant that things didn’t get finished, so that’s why it took a while too. I definitely don’t want to take five years again, and I don’t think that’s gonna happen. [Laughs]

How did you arrive at this new sound?

It started to come together when I realized I wanted to make a record that was fun, because I hadn’t done that yet. Classical Curves was its own thing, and Dream A Garden was preoccupied with a lot of themes in more song-based structures. I wanted this one to capture the thrill I get from some of my favorite music—the drama and fantasy that I hadn’t done on previous records, which were atmospheric and not quite as bold. I found myself moving in that direction in terms of the music I was writing and listening to, and I wanted to make things that were more dynamic.

All the music I was listening to, as disparate as it was, had a sense of performance and affect that’s been a part of rock and pop forever. I felt like it’d be really fun to make music like that. I guess I hadn’t had enough fun yet with making an album. [Laughs]

I talked to Kingdom earlier this year about the early-2010s days of Night Slugs. Tell me about your production approach around that time and how you got into the worlds of dance and electronic music.

I started getting into buying vinyl and turntables, and as I moved to London during the tail end of dubstep and while UK Funky was happening, we were really into that—as well as a lot of underground hip-hop and trap music, jerk, Baltimore club. It was a certain time where all those different threads came together. Night Slugs were DJ’ing all of that at the same time in London. I really got an education in all that music when I moved there, went to those parties, and started making friends with them and the Fade to Mind people.

From there, something clicked. I always wanted to be in a band growing up but I could never find anyone to make music with. I knew I wanted to make music and played instruments a bit, but I never really tried to do that until I was exposed by the drug that is clubbing and dance music. That was like, “OK, here’s something I could maybe use to say something.” I made edits to play for my friends and worked on productions, and having a scene meant I had a built-in audience where I wanted to make music that my friends wanted to play. And they were really supportive in that sense. If I’d been isolated on my own, it’d have been very different.

What I do now is very different in many ways, but I still get motivated by the same impulse where I want to make cool music that the people around me are into. [Laughs] I’m using the same principles to make glam rock that I did to make dance music.

How have you seen the culture around dance and electronic music in the UK change over the last ten years?

At a certain point between my first record and now, I kind of detached from knowing what was really going on in the ground level. Your priorities shift, so I can’t say what those shifts are. But from a distance, not to be pessimistic, there are less clubs and spaces for anyone to make any type of experimental music, or develop a sound away from financial pressures. You can see that in London for sure, and I’m sure it’s similar in New York.

Having said that, I’m still always curious and feeling connected to what’s going on in little corners of SoundCloud and dance music. I always relish catching up on everything every six months and finding loads of new stuff to be excited by. But things are very different from when I got my start. I don’t think it’s possible now for someone like me to make music like that and find something to do with it.

What was the last show you went to see before the pandemic?

Me and my girlfriend saw a Siouxsie and the Banshees tribute band in London. I hadn’t been out that much before that because I was busy with stuff. I miss it even more now. What I wouldn’t do to go to a show, or to a club. I remember seeing Sky Ferreira and Dev Hynes at 285 Kent, and it’s memories like that that keep coming back to me now where I’m like, “Did that even happen?” It all seems so far away now. It’s really depressing. There’s no other way to spin it. I don’t feel too optimistic about the future. I’ve got a lot of good memories now, and I hope there will be more at some point.

Dream A Garden was exploring a lot of sociopolitical themes that people are talking more in a more widespread fashion now.

That record was a time where I was like—talk about becoming woke. For the first time in my life, I was going through a political education through my partner. I was reading a lot of Mark Fisher as well, which was a huge influence and continues to be. So much about it was about myself and how I felt in living in the world, as well as my mental health—politicizing that. “The reason why I feel like shit is because of these guys sitting at the top, not because I was born this way.” That was life-changing in terms of how I saw myself in the world.

I feel better about living in a world where people talk about mental health, capitalism, structrual inequality, bigotry, and racism more. There are so many people who are so much more intelligent about these issues than I could hope to be, and I feel grateful to live in a world where people are listening to them. But also, if you feel something, you should make art about it.

After Brexit and Trump, I wrote so much awful music because it was all my rage. It just came out like how people make fun of “Orange man bad” online. All the songs felt so redundant, like no one would get anything from it, and that was a moment for me as well where I asked what my job was as a musician. I believe in the political power of art, but I’ve learned about the limitations too. Music functions in enriching people in positive ways that go beyond telling people you’re on their side. The opposition to so many structural injustices we face has come to focus so much more. We’re definitely not living in 2015 anymore, and hopefully that’s a good thing.

What went into this new album, thematically?

It’s a bit more of a personal record. I hadn’t really made a personal record yet. The stuff I was reading around Dream A Garden was really informative for me, but it was missing an understanding of what peoples’ emotional needs and desires are. Sometimes they’re not things that are necessarily emancipatory, but they’re nonetheless seductive. It’s an intoxicating vision of the life we want for ourselves—stable, filled with meaning and glamour. We live around constant bombardments of aspirations of wealth and being aroused. That’s the world that’s promised to us, and there’s something bittersweet about that. That’s Pillowland.

This album was a surprise release. How did that play out for you?

Speaking personally, as an audience member, I don’t have patience to wait the three or four weeks between when someone announces their record and when they put it out. There’s something exciting about putting things in peoples’ hands immediately. I’m just going from the gut as far as how I experience things. Pop music comes and goes—it’s a cheap thrill and should be treated as such. I’m not gonna labor over a six-month campaign just to get people to listen to this record.

Even the music press itself isn’t as robust as it was in 2015. A lot of really great publications and writers aren’t around, or they don’t have the muscle they used to. It changes things in that you’re now going straight from the production house to the audience—and I quite like that. I do miss the ecosystem of serious music journalism, but I’m lucky I have a little fanbase and they’re eager to hear from me. If I can get something straight from the oven and into their hands, if it looks and sounds right, then I’m happy to do that.